UN climate chief: less meat = less heat

Dr Rajendra Pachauri, Chair of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, and joint winner of the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize, will present the case that eating less meat can help us fight climate change in an efficient way. Pachauri will deliver the message tomorrow when he presents the Peter Roberts Memorial Lecture titled "Global Warning: the impact of meat production & consumption on climate change", at a conference organised by Compassion in World Farming (CIWF), an animal welfare organisation.

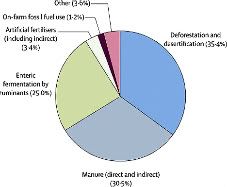

Dr Rajendra Pachauri, Chair of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, and joint winner of the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize, will present the case that eating less meat can help us fight climate change in an efficient way. Pachauri will deliver the message tomorrow when he presents the Peter Roberts Memorial Lecture titled "Global Warning: the impact of meat production & consumption on climate change", at a conference organised by Compassion in World Farming (CIWF), an animal welfare organisation. According to the FAO, global livestock production is responsible for more greenhouse gas emissions than the entire transport sector (previous post). Cutting back on it can prevent the release of large amounts of methane, CO2 and N2O, which are emitted during the long production chain of meat, from field to fork. A large fraction of these emissions arise from tropical forests that are cleared to make way for cattle feed production. Other main sources are the fermentation of feed by ruminants and the emissions from manure (graph, click to enlarge).

According to the FAO, global livestock production is responsible for more greenhouse gas emissions than the entire transport sector (previous post). Cutting back on it can prevent the release of large amounts of methane, CO2 and N2O, which are emitted during the long production chain of meat, from field to fork. A large fraction of these emissions arise from tropical forests that are cleared to make way for cattle feed production. Other main sources are the fermentation of feed by ruminants and the emissions from manure (graph, click to enlarge).According to Henning Steinfeld, Chief of FAO’s Livestock Information and Policy Branch and senior author of a recent report entitled Livestock's long shadow - Environmental issues and options, “livestock are one of the most significant contributors to today’s most serious environmental problems. Urgent action is required to remedy the situation.”

With increased prosperity, people are consuming more meat and dairy products every year. Global meat production is projected to more than double from 229 million tonnes in 1999/2001 to 465 million tonnes in 2050, while milk output is set to climb from 580 to 1043 million tonnes.

The global livestock sector is growing faster than any other agricultural sub-sector. It provides livelihoods to about 1.3 billion people and contributes about 40 percent to global agricultural output. For many poor farmers in developing countries livestock are also a source of renewable energy for draft and an essential source of organic fertilizer for their crops.

But such rapid growth exacts a steep environmental price. “The environmental costs per unit of livestock production must be cut by one half, just to avoid the level of damage worsening beyond its present level,” the FAO report warns. When emissions from land use and land use change are included, the livestock sector accounts for 9 percent of CO2 deriving from human-related activities, but produces a much larger share of even more harmful greenhouse gases. It generates 65 percent of human-related nitrous oxide, which has 296 times the Global Warming Potential (GWP) of CO2. Most of this comes from manure.

And it accounts for respectively 37 percent of all human-induced methane (23 times as warming as CO2), which is largely produced by the digestive system of ruminants, and 64 percent of ammonia, which contributes significantly to acid rain:

energy :: sustainability :: biomass :: bioenergy :: farming :: deforestation :: livestock :: meat :: greenhouse gas emissions :: obesity ::

energy :: sustainability :: biomass :: bioenergy :: farming :: deforestation :: livestock :: meat :: greenhouse gas emissions :: obesity :: There are various possibilities for reducing the greenhouse gas emissions associated with farming animals. They range from scientific approaches, such as genetically engineering strains of cattle that produce less methane flatus, to reducing the amount of transport involved through eating locally reared animals.

Farmers in Europe strongly support research aimed at reducing methane emissions from livestock farming by, for example, changing diets and using anaerobic digestion to produce biogas.

At the CIFW conference, Dr Pachauri will especially urge people in wealthy countries to lower their meat consumption. This will free up resources to feed the billions of poorer people who cannot currently afford animal protein, but who could benefit from it healthwise.

Changing diets in highly developed countries would also benefit the health of wealthier people. Overconsumption of meat products has contributed in a significant way to the obesity pandemic and its related health problems. A many a 'food pyramid' shows, red meat, dairy products, poultry and fish should only form a small part of a healthy diet.

CIWF's ambassador Joyce D'Silva said that thinking about climate change as well as the health benefits of eating less meat, could spur people to change their habits. "The climate change angle could be quite persuasive," she thinks. "Surveys show people are anxious about their personal carbon footprints and cutting back on car journeys and so on; but they may not realise that changing what's on their plate could have an even bigger effect."

Ms D'Silva believes that governments negotiating a successor to the Kyoto Protocol ought to take the emissions from livestock production into account. "I would like governments to set targets for reduction in meat production and consumption," she said.

That is something that should probably happen at a global level as part of a negotiated climate change treaty, and "it would be done fairly, so that people with little meat at the moment such as in sub-Saharan Africa would be able to eat more, and we in the west would eat less."

Dr Pachauri, however, sees it more as an issue of personal choice. "I'm not in favour of mandating things like this, but if there were a (global) price on carbon perhaps the price of meat would go up and people would eat less," he said. "But if we're honest, less meat is also good for the health, and would also at the same time reduce emissions of greenhouse gases."

Graph: Proportion of greenhouse-gas emissions from different parts of livestock production. Adapted from FAO.

References:

CIFW Peter Roberts Memorial Lecture: "Global Warning: the impact of meat production & consumption on climate change".

CIFW: Global warning: climate change and farm animal welfare [*.pdf] - 2007.

CIFW: Impact of livestock farming: solutions for animals, people and the planet [*.pdf] - 2007.

Biopact: FAO: Livestock a major environmental and climate threat; implications for bioenergy - December 06, 2006

--------------

--------------

Mongabay, a leading resource for news and perspectives on environmental and conservation issues related to the tropics, has launched Tropical Conservation Science - a new, open access academic e-journal. It will cover a wide variety of scientific and social studies on tropical ecosystems, their biodiversity and the threats posed to them.

Mongabay, a leading resource for news and perspectives on environmental and conservation issues related to the tropics, has launched Tropical Conservation Science - a new, open access academic e-journal. It will cover a wide variety of scientific and social studies on tropical ecosystems, their biodiversity and the threats posed to them.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Links to this post:

Create a Link

<< Home