New meta-study sheds doubt on reliability of climate models

Even though there is an overwhelming scientific consensus on the fact that humans are responsible for climate change, there remains controversy and doubt over the reliability of climate models used to forecast future changes. A new study comparing the composite output of 22 leading global climate models with actual climate data finds that the models do an unsatisfactory job of mimicking climate change in key portions of the atmosphere.

Even though there is an overwhelming scientific consensus on the fact that humans are responsible for climate change, there remains controversy and doubt over the reliability of climate models used to forecast future changes. A new study comparing the composite output of 22 leading global climate models with actual climate data finds that the models do an unsatisfactory job of mimicking climate change in key portions of the atmosphere.The 22 climate models used in the study are the same models used by the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (see the IPCC's own evaluation of climate models, in Chapter 8 of the Working Group I Report, 'The Physical Science Basis'). The usual discussion is whether the climate model forecasts of Earth's climate 100 years or so into the future are realistic, says lead author Dr. David H. Douglass from the University of Rochester. But the new study asks a more fundamental question: can these same models accurately explain the climate from the recent past? It seems that the answer is no.

Scientists from Rochester, the University of Alabama in Huntsville (UAH) and the University of Virginia who publish their findings in the Royal Meteorological Society's International Journal of Climatology, compared the climate change forecasts from the 22 most widely-cited global circulation models with tropical temperature data collected by surface, satellite and balloon sensors. The models predicted that the lower atmosphere should warm significantly more than it actually did.

Models are very consistent in forecasting a significant difference between climate trends at the surface and in the troposphere, the layer of atmosphere between the surface and the stratosphere, says Dr. John Christy, director of UAH's Earth System Science Center. The models forecast that the troposphere should be warming more than the surface and that this trend should be especially pronounced in the tropics.

But when the researchers looked at actual climate data, however, they did not see accelerated warming in the tropical troposphere. Instead, the lower and middle atmosphere was warming the same or less than the surface. In layers near 5 km, the modelled trend was 100 to 300% higher than observed, and, above 8 km, modelled and observed trends even have opposite signs. For those layers of the atmosphere, the warming trend they observed in the tropics is typically less than half of what the models forecast, shedding serious doubt on the reliability of the models.

The atmospheric temperature data were obtained from two versions of data collected by sensors aboard NOAA satellites since late 1979, plus several sets of temperature data gathered twice a day at dozens of points in the tropics by thermometers carried into the atmosphere by helium balloons. The surface data were from three datasets:

energy :: sustainability :: biomass :: bioenergy :: climate change :: global warming :: global climate model :: forecast :: IPCC ::

energy :: sustainability :: biomass :: bioenergy :: climate change :: global warming :: global climate model :: forecast :: IPCC :: After years of rigorous analysis and testing, the high degree of agreement between the various atmospheric data sets gives an equally high level of confidence in the basic accuracy of the climate data.

The last 25 years constitute a period of more complete and accurate observations, and more realistic modeling efforts, says Dr. Fred Singer from the University of Virginia. Nonetheless, the models are seen to disagree with the observations. The researchers suggest, therefore, that projections of future climate based on these models should be viewed with much caution.

Contradictions

The findings of this study contrast strongly with those of a recent analysis that used 19 of the same climate models and similar climate datasets. That study concluded that any difference between model forecasts and atmospheric climate data is probably due to errors in the data.

The question was, what would the models 'forecast' for upper air climate change over the past 25 years and how would that forecast compare to reality? To answer that, the scientists needed climate model results that matched the actual surface temperature changes during that same time. If the models got the surface trend right but the tropospheric trend wrong, then they could pinpoint a potential problem in the models.

As it turned out, the average of all of the climate models forecasts came out almost like the actual surface trend in the tropics. That meant the researchers could do a very robust test of their reproduction of the lower atmosphere.

Instead of averaging the model forecasts to get a result whose surface trends match reality, the earlier study looked at the widely scattered range of results from all of the model runs combined. Many of the models had surface trends that were quite different from the actual trend, Christy says. Nonetheless, that study concluded that since both the surface and upper atmosphere trends were somewhere in that broad range of model results, any disagreement between the climate data and the models was probably due to faulty data.

The researchers think their new experiment is more robust and provides more meaningful results.

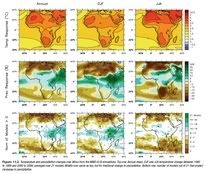

Illustration: projections of temperature and precipitation changes in Africa due to climate change, indicating the number of climate models used. Credit: IPCC, Fourth Assessment Report, The Physical Science Basis, Chapter 9.

References:

David H. Douglass, John R. Christy, Benjamin D. Pearson, S. Fred Singer, "A comparison of tropical temperature trends with model predictions (p n/a)", International Journal of Climatology, Dec 5 2007, DOI: 10.1002/joc.1651

Eurekalert: New study increases concerns about climate model reliability - December 11, 2007.

--------------

--------------

The Royal Society of Chemistry has announced it will launch a new journal in summer 2008, Energy & Environmental Science, which will distinctly address both energy and environmental issues. In recognition of the importance of research in this subject, and the need for knowledge transfer between scientists throughout the world, from launch the RSC will make issues of Energy & Environmental Science available free of charge to readers via its

The Royal Society of Chemistry has announced it will launch a new journal in summer 2008, Energy & Environmental Science, which will distinctly address both energy and environmental issues. In recognition of the importance of research in this subject, and the need for knowledge transfer between scientists throughout the world, from launch the RSC will make issues of Energy & Environmental Science available free of charge to readers via its

1 Comments:

RealClimate has now addressed the Douglass et al paper -- their interpretation is that the authors fail to take into account the margin of error in the (raw) radiosonde data. "Adjusted" radiosonde datasets have been published which match the model predictions much more closely.

Post a Comment

Links to this post:

Create a Link

<< Home