Ecology, poverty and energy: the case for biofuels in Africa

In this essay, Marguerite Culot analyses how the environment, poverty and energy are intertwined issues that need to be addressed in an integrated way to make sustainable development in poor countries a reality. Energy is at the heart of the great social, economic and environmental challenges that face humanity. Investments in smart bioenergy and biofuels offer a pragmatic and realistic way to achieve this goal amongst the vast rural populations of the African continent, she argues. Marguerite Culot is an expert in human rights as they relate to natural resource exploitation, and has worked extensively in Africa. She put her expertise at work for Ethical Sugar, a Paris-based NGO, as well as in projects relating to renewable energy in developing countries.

In this essay, Marguerite Culot analyses how the environment, poverty and energy are intertwined issues that need to be addressed in an integrated way to make sustainable development in poor countries a reality. Energy is at the heart of the great social, economic and environmental challenges that face humanity. Investments in smart bioenergy and biofuels offer a pragmatic and realistic way to achieve this goal amongst the vast rural populations of the African continent, she argues. Marguerite Culot is an expert in human rights as they relate to natural resource exploitation, and has worked extensively in Africa. She put her expertise at work for Ethical Sugar, a Paris-based NGO, as well as in projects relating to renewable energy in developing countries.The majority of Africans live in rural zones, where modern energy services are generally absent, she writes in NaturaVox a leading publication on sustainable development. Whereas access to energy is the basis of development, we must work to support the clean supply of energy in rural areas. This is the key to sustainable development on the African continent.

The energy situation in Africa

The level of economic and social development of the continent - which is characterized in general by a rural economy, with a weak contribution of industry to gross domestic product, lower than 20% for a number of countries; an extensive agricultural sector, little mechanized, with very poor yields; a vast poor population, only moderately urbanized - reflects its energy situation.

The level of economic and social development of the continent - which is characterized in general by a rural economy, with a weak contribution of industry to gross domestic product, lower than 20% for a number of countries; an extensive agricultural sector, little mechanized, with very poor yields; a vast poor population, only moderately urbanized - reflects its energy situation.The majority of the studies on the energy situation of Africa indeed reveal a high level of energy poverty characterized by a low per capita energy consumption, often merely limited to the use of fuels for heating and to cook food. Table 1 (click to enlarge) illustrates this energy poverty and the weak progress made since 1996 vis-a-vis an ever increasing population.

One can observe slow growth in the French-speaking countries of Sahel and West Africa. On the other hand, the trend is one of stagnation or even regression in the countries of Central Africa - the political context of instability since the 1990s certainly being the leading cause. As a whole, Africa has the lowest per capita energy consumption on earth. People in African countries consume around 150 times less energy than those in the industrialized world.

A third of all Africans does not have access to electricity (the modern form of energy par excellence). But even if more and more rural electrification investments are made and access is improved, the poor populations at large seldom have the financial means to pay for electric power at market prices; their only alternative until now has been to turn to traditional biomass to meet their requirements.

It is important to note that the bulk of the energy consumed by the great majority of African countries remains dominated by traditional biomass, which often represents three quarters of the consumed primary energy. This traditional biomass - fuel wood, charcoal,the burning of agricultural residues - does not offer a sustainable path forward for African countries. On the one hand, the increased use of traditional biomass results in negative impacts on pubic health (in particular respiratory and pulmonary disease from indoor smoke pollution), on the other, it is highly inefficient and burdens women and children who face the effort of collecting wood.

The increased use of traditional biomass, often spontaneous and non-rational, is characterized by a set of great ecological problems: deforestation, desertification, a reduction in the duration of leaving land fallow. In addition, because of a rapid population increase and because traditional biomass resources are limited, we can doubt the capacity of this resource to meet the future the energy needs in light of demographic trends.

Other solutions should thus be found to allow populations to obtain increased access to energy, enabling them to live with dignity and to build a future. In what follows, I explore how the development of modern energy is key to the fight against poverty and show how access to energy and social development are intertwined issues.

Energy and the MDGs

Energy poverty is the rule in Africa. Rural populations - let us recall that the great majority of the people of the continent lives in rural zones - often only have access to traditional biomass to meet their energy needs. This situation traps Africans in poverty: a vicious circle of impoverishment fueled by the exhaustion of renewable resources, in turn preventing sustainable social and economic development.

Initially, access to energy is used to meet the most basic social needs: for professional purposes, for transport and for education and health care, to list but a few. In a next phase, energy is essential for economic growth. Without energy, productive activities in the agricultural, industrial or the service sector are impossible? The Johannesburg Declaration on Sustainable Development therefor explicitly recognizes the privileged place of energy in the promotion of sustainable human development and affirms that all the human activities depend on access to energy.

Energy is indeed the engine of industry, allows for more efficient and less back breaking agriculture and especially meets multiple socio-economic needs. The correlation between access to energy and the degree of human development is well established:

ethanol :: biodiesel :: biomass :: bioenergy :: biofuels :: energy security :: sustainability :: rural development :: poverty alleviation :: Millennium Development Goals :: Africa ::

ethanol :: biodiesel :: biomass :: bioenergy :: biofuels :: energy security :: sustainability :: rural development :: poverty alleviation :: Millennium Development Goals :: Africa :: Energy is truly at the heart of the answers which society must bring to the great current social challenges facing this world:

- To reduce poverty by the improvement of health and the increase in productivity, by ensuring a universal access to adequate energy services for cooking, lighting, transport; ensuring the creation of income-generating activities to alleviate poverty.

- To release the women of the burdens of collecting wood, water and preparing food, and to improve quality of the air in the household to prevent respiratory diseases.

- To attenuate the problems related to the fast and uncontrolled urbanization by fixing rural populations in their environment: this can be achieved by the improvement of access to modern energy services, such as mechanised tools, irrigation pumps, harvesting and processing machines, transport services to move agricultural products to markets

An efficient and universal supply of energy contributes directly to the achievement of 7 of the 8 MDGs:

- goal 1: to halve the incidence of extreme poverty by 2015

- goal 2: to achieve universal primary education

- goal 3: to promote gender equality and empower women

- goal 4: reducing child mortality

- goal 5: improving maternal health

- goal 7: ensuring environmental sustainability, with the sub-objective of improving access to drinking water in rural areas

- goal 8: developing a global partnership for development, with the sub-objective of achieving greater employment of young people in rural areas

Biofuels are a potential source of modern energy for rural areas and can provide improved access to fuels to the poorest populations. They can contribute in a considerable way to the fight against poverty. Let us have a closer look at this role of biofuels.

The contribution of biofuels to achieving the MDGs

On a global level, the state and future of energy has reached an alarming status. Whereas some announce that 'Peak Oil' will be here before the year 2030, others predict that gas reserves will run out by the end of the century. Moreover, uranium reserves are finite and not renewable, whereas hydrogen does not represent a primary source of energy but is merely an energy carrier.

Renewable forms of energy offer major opportunities for the future, but they have achieved only a limited share of the world's energy mix so far. The problem of the intermittency of sources such as wind and solar power has not been solved in a satisfactory manner.

Consequently, biofuels and bioenergy - not plagued by the problem of intermittency, renewable, and useable in existing infrastructures - have an important role to play in the universal supply of energy, particularly in the poorest countries.

Because the raw materials needed to produce biofuels can be grown virtually anywhere, but especially in Africa, where the arable land base is very large, and whose production does not require enormous investments, can start a cycle of economic growth and support social progress.

Africa's energy assets - a future of possibilities

The low level of development of the African energy sector is not a result of the scarcity of energy resources because Africa has enormous renewable energy potential: (1) hydropower, (2) geothermal, solar energy and wind resources, (3) sustainable, modern bioenergy.

In principle, energy should not be handicap, but on the contrary, a genuine engine of African economic growth. Currently, there is a lack of concrete initiatives aimed at tapping the vast renewable energy potential.

In the majority of the African countries, the share of renewables remains extremely marginal (for example, less than 0,1% in the energy mix of the countries of the UEMOA). Spme efforts to tap thermal and solar resources have been made, with applications in the field of water pumping, lighting and rural electrification. More than 120,000 photovoltaic systems, worth more than 3 MW, have been installed across Africa, but mainly in South Africa and Kenya.

The lack of modern technologies for the valorization of Africa's large biomass resources, means biomass is currently used in an extremely inefficient manner for cooking and heating (open fires, which lose up to 90% of the energy contained in biomass).

With the introduction of modern technologies centered on a rational use of biomass, African countries can reduce domestic energy consumption and fuel sectors currently dependent on fossil fuels (the industrial sector in particular), which would support their development in the long term. The current situation constitutes the essential energy paradox of Africa: an abundance of resources, but a lack of development and rational use of these resources.

But there is room for optimism in the near future, when one looks at the various plans and projects being initiated across the continent. African countries indeed are analysing the ways in which to utilize their resources in the most optimal and sustainable way.

With this perspective in mind, we can analyze how biofuels will contribute positively to Africa's development.

Which type of biofuels for sub-Saharan Africa?

The majority of African countries (especially of Southern Africa and West Africa) have worked out or are working on national biofuels policies and strategies. Biomass can be transformed to yield liquid, solid or gaseous fuels depending on the conversion technology and raw material used.

Biomass is a generic term meaning all organic matter useable for energy production, such as plant matter, trees, energy crops, livestock waste, agricultural residues and organic municipal waste.

There are roughly three approaches to the production of biofuels:

1) The alcohol pathway: fuels produced by the fermentation of sugars or starch, in dedicated plants, biorefineries or in ethanol facilities related to sugar refineries. Bioethanol is never used directly in its pure form, and requires blending into gasoline. However, vehicles adapted to run on ethanol are being marketed both in the EU, the US and Brazil - socalled flex-fuel cars.

Another alcohol fuel is ETBE, a mixture of 47% ethanol and 53% isobutylene blended in gasoline.

Africa could use bioethanol produced on the continent provided it succeeds in replacing its old car fleet. This fleet is however primarily composed of old models imported from Europe, so this transition will not happen anywhere soon.

However, with strong policies, it can be done. An example is offered by Malawi which has been producing, since the energy crisis of the beginning of the 1970s, ethanol from sugarcane molasses. The Malawian government is currently financing a five year project aimed at exploring the possibility vehicle conversions so they can burn the biofuel. According to Daniel Liwimbi, general manager of the ETHCO, the government must nevertheless conceive a strategy of adequate planning in order to increase the output of ethanol, so that it meets the needs for the whole of the population: "the government should envisage to increase the production of ethanol if it wants that this project to be a success". By increasing the production of molasses, Malawi could reach a capacity of 30 million liters per season.

In addition to transport fuels, ethanol can also have a very profitable use as a fuel for cooking and lighting, namely in the form of gelfuels or gelled ethanol. This product has a future even though it is currently rather expensive compared to traditional biomass fuels. With rising prices of kerosene and other fossil fuels used for heating, cooking and lighting, gelfuels will become more competitive.

2) the vegetable oil pathway: first generation biodiesel produced from oilseeds such as sunflower, soya, palm, ricinus, jatropha, etc. The dedicated production of these oils for biofuels has not taken off yet in Africa and remains tied to food processing factories.

Vegetable oils are full of energy, and can be used as such, directly as energy in the form of food or in engines which replace the energy spent on manual labor.

Byproducts from the production of oil are oil cakes rich in plant protein, which can be used as cattle feed.

Biodiesel obtained from the transesterification of vegetable oils - an industrial product - is blended with petrodiesel and can be readily used in most existing diesel engines. Pure plant oil (PPO) can be utilized in engines after small modifications.

Biodiesel and PPO offer interesting prospects in Africa. The culture of oilseed rich shrubs and other oleiferous species cultivable in arid or semi-arid regions, such as jatropha, the karanj (pongamia pinnata), the moringa (mohinga), the butter tree (honey tree, mahua), and other plants offer much hope: they are very rich in oil, does not require much water and have multiple uses (e.g. as protective hedges around farm fields). Other native plants exist and can also provide oil on a local level.

The oilseeds pathway is very interesting for Africa, but on that careful social and environmental impact studies are carried out for plantations.

3) second generation biofuels: these are the most interesting and efficient but will be developed first in industrialised countries. Such biofuels can be produced from any type of biomass, including the agricultural residues of which there is an large resource base.

Conversion pathways are under development and are receiving lots of research funding. They can be broken down in two categories: a biochemical conversion pathway (cellulosic ethanol, biohydrogen), and thermochemical conversion (pyrolysis, gasification).

Second generation biofuels are beneficial in multiple ways: they can draw on dedicated energy crops produced by both small and large agricultural operations; on forest residues and dedicated silviculture; but also on existing biomass residues, such as agricultural and processing waste products (straw, husks, hulls, mill effluents, and so on). This takes away any potential competition between food and fuels.

The production of next generation biofuels is more energy efficient because it requires less fossil fuel inputs during the production and transformation of raw materials.

In conclusion, for the time being, Africa will benefit most from the production of biodiesel made from non-food crops grown on land less suitable for food production, and ethanol from sugarcane and sorghum. These biofuels can increasingly meet the fuel needs of Africa's growing populations, while cutting dependence on expensive fossil fuels.

[Marguerite Culot then provides an extensive overview of current and planned biofuel projects in Africa, most notably in Madagascar, Benin, Tanzania, Senegal and Mali. Projects range from the creation of a multipurpose vehicle used to transport people and provide electricity generating capacities, to a multifunctional platform running on vegetable oil and used for milling agricultural products, to the development of highly efficient and clean cooking stoves utilizing biofuels.]

Biofuels and social equity

The level of access to energy in Africa is very low. This general level however hides disparities not only between countries but within countries: urban populations are being served much better than the larger peri-urban and rural populations.

The rate of rural electrification for example seldom exceeds 8% in the majority of African countries.

For this reason, the production of oil crops, tied to rural economies, can close this gap. When consumed at the local level, biofuels would allow the democratization of the access to energy. The production of biofuels is both socially and economically profitable and has a better environmental profile when the place of plantation, production and consumption are identical.

Governments can therefor develop energy strategies with the explicit purpose of benefiting rural populations, if they encourage the production of biofuels in rural areas and with the aim to use them locally. Policies aimed at exporting biofuels are interesting, but should come in second place. Such a strategy can be summarized as: local production for local consumption, with the surplus going to export.

In this way, the production of biofuels supports the energy autonomy of the rural populations, contributes to rural development, and takes people out of the vicious circle of poverty. [Culot then provides the example of the development of the multifunctional platform developed by the UNDP and a consortium of international partners, which relies on local biofuel production and use in the platform which helps with many common tasks found in rural areas, such as milling food and pumping water.]

Other advantages of biofuels

Biofuels offer a wealth of social and economic advantages both on a local, regional, national and global level:

- The reduction of the energy dependence of non-producing oil countries: let us recall that for many African countries, oil imports constitute more than 50 % of the value of all of their imports - a heavy burden

- Creation of jobs: stimulation of the local economy, especially for SMEs and cooperatives. Currently, the majority of the farmers in rural zones are subsistence farmers. They could profit from the energy culture if food safety is not affected and if they are systematically engaged in the production process of biofuels and not merely as raw material suppliers. The African countries should undoubtedly encourage peasants to unite in cooperatives to sell at good prices to local factories. [Culot discusses the Brazilian 'Social Fuel' policy, which is benefiting 70,000 poor farmer families as an example of such a strategy.]

- Creation of added value in rural zones and a better valorization of the agricultural outputs related to biofuel production, such as seed cakes, chemicals for the production of soap, animal feed, organic fertilizer and so on.

- Reductions in greenhouse gas emissions and consequently a considerable contribution in the fight against climate change, which will affect the poorest first and most.

- Interesting opportunities to solve the problem of access to water for populations located in arid and semi-arid regions: biofuels made from drought-tolerant crops (such as karanj, pongamia or jatropha) can help conserve wood resources and help in irrigation and water pumping

- The possibility of rotating and alternating crops by combing food and energy production or by switching from food to energy or vice-versa: this will benefit farmers who were previously dependent on single crops for which world prices have often collapsed

- Providing fuels for transport in agriculture; without good access to cheap transport fuels, farmers fail to bring products to markets with poverty as a consequence

- Increased incomes for small farmers, under certain conditions, when production of biofuels is tied to direct sales or direct consumption and the elimination of intermediaries and large investments; this is achievable when fuels are produced by cold pressing and not requiring sophisticated and expensive machines nor chemicals.

- Incomes from and improved access to a multitude of by-products: oil cakes for animal feeds and manure, glycerin for manufacture of soaps, pharmaceutical products

- Valorization of 'waste' streams resulting from the production of biofuels by producing biogas (methane) which can be used locally as a clean fuel for lighting, heating and cooking, or on a larger scale for cogeneration and as a transport fuel

According to the FAO, biofuels and bioenergy could become the engine of rural development provided governments craft smart policies.

Africa abounds in renewable energy resources. It is true, however, that these resources are unequally distributed, but this situation offers interesting possibilities for cooperation, and indeed, even for energy integration of the entire continent.

A possible strategy, currently being developed by NEPAD, is precisely founded on the exploitation of this potential by integrating different national efforts to set in motion the development of a continent-wide, integrated energy program. But before such a large cooperation and integration effort is undertaking, national governments must first develop energy programs suited to their populations' own needs and based on renewables.

Likewise, each African country should develop its own strategy for biofuels, with a view on utilizing them first to supply their own markets. The countries should help each other, share best practices and transfer technologies. South-South partnerships between, for example Brazil and African countries, should be encouraged too [Culot discusses these initiatives in depth].

Marguerite Culot is an expert in sustainable development in Africa, focusing on human rights and natural resource exploitation. She has worked in Mali on a biofuel project for rural populations, and on a range of other projects on the continent. Culot has been a researcher with Sucre Éthique, a Paris-based NGO aiming to stimulate corporate social responsibility in the sugar sector which employs millions of poor farmers in the developing world. Culot publishes frequently on sustainable development and energy in Africa.

Translated for Biopact by Laurens Rademakers

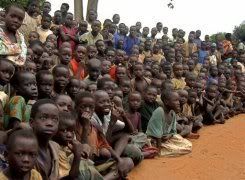

Photo: a new generation of people in Côte d'Ivoire, facing energy questions. Credit: Ivorian Green Party.

References:

NaturaVox: Environnement, pauvreté et énergie : l’interdépendance - December 2007.

Biopact: Leading scientists: energy crisis poses major 21st century threat, action needed now - October 23, 2007

--------------

--------------

PetroChina Co Ltd, the country's largest oil and gas producer, plans to invest 800 million yuan to build an ethanol plant in Nanchong, in the southwestern province of Sichuan, its parent China National Petroleum Corp said. The ethanol plant has a designed annual capacity of 100,000 tons.

PetroChina Co Ltd, the country's largest oil and gas producer, plans to invest 800 million yuan to build an ethanol plant in Nanchong, in the southwestern province of Sichuan, its parent China National Petroleum Corp said. The ethanol plant has a designed annual capacity of 100,000 tons.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Links to this post:

Create a Link

<< Home