Study: carbon dioxide reacts quickly with underground rocks, makes safe geosequestration feasible

Storing carbon dioxide deep below the earth’s surface could be a safe, long-term solution to one of the planet’s major contributors to climate change. University of Leeds research shows that porous sandstone, drained of oil by the energy giants, could provide a safe reservoir for carbon dioxide. The study found that sandstone reacts with injected fluids more quickly than had been predicted - such reactions are essential if the captured CO2 is not to leak back to the surface.

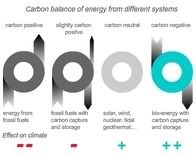

Storing carbon dioxide deep below the earth’s surface could be a safe, long-term solution to one of the planet’s major contributors to climate change. University of Leeds research shows that porous sandstone, drained of oil by the energy giants, could provide a safe reservoir for carbon dioxide. The study found that sandstone reacts with injected fluids more quickly than had been predicted - such reactions are essential if the captured CO2 is not to leak back to the surface.Biopact tracks developments in research into geosequestration and carbon capture and storage (CCS), because these technologies can be coupled to bioenergy, resulting in carbon-negative fuels and energy (more here). Contrary to all other renewables, which are merely 'carbon-neutral', bioenergy coupled to CCS takes historic CO2 emissions out of the atmosphere (schematic, click to enlarge). Biopact is collaborating on an article on carbon negative bioenergy, to appear in Energy Policy.

Safe and durable storage of CO2 is one of the key requirements to make CCS practicable. The Leeds study adds to the growing body of science on how CO2 reacts with the geological elements and formations in which it would be stored. Results are published in the December issue of Geology.

The researchers looked at data from the Miller oilfield in the North Sea, where BP had been pumping seawater into the oil reservoir to enhance the flow of oil. The study covered samples of water pumped out from the Miller oilfield over a seven-year period. The data is routinely collected by BP to assess whether water-borne chemicals are liable to cause costly problems of scale to the drilling equipment. The Leeds scientists compared these with the composition of the water that was there before and the water that was injected. This showed that minerals had grown and dissolved as the water travelled through the field.

Significantly, PhD student Stephanie Houston found that water pumped out with the oil was especially rich in silica. This showed that silicates, usually thought of as very slow to react, had dissolved in the newly-injected seawater over less than a year. This is the type of reaction that would be needed to make carbon dioxide stable in the pore waters, rather like the dissolved carbonate found in still mineral water.

The study gives a clear indication that carbon dioxide sequestered deep underground could also react quickly with ordinary rocks to become assimilated into the deep formation water:

energy :: sustainability :: biomass :: bioenergy :: biofuels :: carbon capture and storage :: geosequestration :: carbon-negative :: bio-energy with carbon storage :: climate change ::

energy :: sustainability :: biomass :: bioenergy :: biofuels :: carbon capture and storage :: geosequestration :: carbon-negative :: bio-energy with carbon storage :: climate change :: The work was supervised by Bruce Yardley, Professor in the School of Earth and Environment at the University, who explained: “If CO2 is injected underground we hope that it will react with the water and minerals there in order to be stabilized. That way it spreads into its local environment rather than remaining as a giant gas bubble which might ultimately seep to the surface.

“It had been thought that reaction might take place over hundreds or thousands of years, but there’s a clear implication in this study that if we inject carbon dioxide into rocks, these reactions will happen quite quickly making it far less likely to escape.”

Although extracting CO2 from power stations and storing it underground has been suggested as a long-term measure for tackling climate change, it has not yet been put to work for this purpose on a large scale. “There is one storage project in place at Sleipner, in the Norwegian sector of the North Sea, and some oil companies have actually used CO2 sequestration as a means of pushing out more oil from existing oilfields,” said Prof Yardley.

In the UK the Prime Minister has recently announced a major expansion of energy from renewable sources and the launch of a competition to build one of the world's first carbon capture and storage plants. The Leeds study suggests the technique has long-term potential for safely storing this major by-product of our power stations, rather than allowing it to escape and further contribute to global warming.

Stephanie Houston worked on the project as part of an Industrial Case Studentship, funded by the Natural Environment Research Council and BP. Her work was supervised by Professor Bruce Yardley, who is based in the Institute of Geological Sciences within the School of Earth and Environment at the University of Leeds.

References:

Stephanie J. Houston, Bruce W.D. Yardley, P. Craig Smalley, and Ian Collins, "Rapid fluid-rock interaction in oilfield reservoirs", Geology, Volume 35, Issue 12, (December 2007), pp. 1143–1146.

Eurekalert: Planting carbon deep in the earth - rather than the greenhouse - November 26, 2007.

--------------

--------------

German industrial conglomerate MAN AG plans to expand into renewable energies such as biofuels and solar power. Chief Executive Hakan Samuelsson said services unit Ferrostaal would lead the expansion.

German industrial conglomerate MAN AG plans to expand into renewable energies such as biofuels and solar power. Chief Executive Hakan Samuelsson said services unit Ferrostaal would lead the expansion.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Links to this post:

Create a Link

<< Home