FAO forecasts continued high cereal prices: bad weather, low stocks, soaring demand, biofuels, high oil prices cited as causes

Global cereal prices are expected to remain at high levels for the coming year due largely to problems in production in several major exporting countries and very low world stocks, says the latest Food Outlook report issued today by FAO in London. The convergence and interaction of a whole range of particular circumstances is the main cause for high prices and volatility in agricultural commodity markets: unfavourable weather in key production areas, low stocks, tight supplies, strong demand from rapidly growing economies, biofuels, record petroleum prices, high freight rates, currency developments and a high degree of speculation.

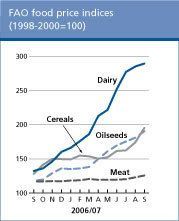

Global cereal prices are expected to remain at high levels for the coming year due largely to problems in production in several major exporting countries and very low world stocks, says the latest Food Outlook report issued today by FAO in London. The convergence and interaction of a whole range of particular circumstances is the main cause for high prices and volatility in agricultural commodity markets: unfavourable weather in key production areas, low stocks, tight supplies, strong demand from rapidly growing economies, biofuels, record petroleum prices, high freight rates, currency developments and a high degree of speculation. The FAO food price index rose by 9 percent in 2006 compared with the previous year. In September 2007 it stood at 172 points, representing a year-on-year jump in value of roughly 37 percent (graph 1, click to enlarge). The surge in prices has been led primarily by dairy and grains, but prices of other commodities have also increased significantly. The only exception is the price of sugar, which has been declining for the second year in a row. This trend occured despite record sugar based ethanol output in Brazil (graph 2, click to enlarge).

The FAO food price index rose by 9 percent in 2006 compared with the previous year. In September 2007 it stood at 172 points, representing a year-on-year jump in value of roughly 37 percent (graph 1, click to enlarge). The surge in prices has been led primarily by dairy and grains, but prices of other commodities have also increased significantly. The only exception is the price of sugar, which has been declining for the second year in a row. This trend occured despite record sugar based ethanol output in Brazil (graph 2, click to enlarge).High price events, like low price events, are not rare occurrences in agricultural markets although often high prices tend to be short lived compared with low prices, which persist for longer periods. What distinguishes the current state of agricultural markets is rather the concurrence of the hike in world prices of, not just a selected few, but of nearly all, major food and feed commodities. As has become evident in recent months, high international prices for food crops such as grains continue to ripple through the food value/supply chain, contributing to a rise in retail prices of such basic foods as bread or pasta, meat and milk.

Rarely has the world witnessed such a widespread and commonly shared concern about food price inflation, a fear which is fuelling debates about the future direction of agricultural commodity prices in importing as well as exporting countries, be they rich or poor. - FAO Food OutlookThe price boom has also been accompanied by much higher price volatility than in the past, especially in the cereals and oilseeds sectors (more on the importance of volatility below). Increased volatility highlights the prevalence of greater uncertainty in the market. Supply tightness in any commodity market often raises price volatility in that market. Yet, the current situation differs from the past in that the price volatility has lasted longer, a feature that is as much a result of supply tightness as it is a reflection of ever-stronger relationships between agricultural commodity markets and other markets.

Among major cereals, this season’s main protagonist is wheat, the supply of which has been hampered by production shortfalls in Australia, a major exporter, and low world stocks, while demand has been strong, not only for food but also feed. In September, wheat was traded at record prices, between 50 and 80 percent above last year. Maize prices increased progressively from the middle of last year until February 2007, when they hit a ten-year high, but have fallen considerably since. Supply constraints in the face of brisk demand for biofuels triggered the initial price hike in maize prices. However, reacting to a massive expansion in plantings and expectations of a record crop this year, prices have started to come down, although by September they had still remained 30 percent above last year. Prices of barley, another important cereal, also soared lately. Supply problems in Australia and Ukraine, tighter availability of maize and other feed grains, compounded with strong import demand, have contributed to the doubling of prices of both feed and malting barley in recent weeks.

The tightness in the grain sector also affected the oilseed complex, which witnessed a year-on-year price surge of at least 40 percent, depending on crops and products. Soaring maize markets during the second half of the previous season contributed to keeping oilseed prices at high levels as maize plantings expanded at the expense of oilseed plantings. Due to the expected shrinking of world supplies and historically low inventories in 2007, in the face of faster rising demand for food and biodiesel, as well as unusually strong demand for feed, oilseed markets are experiencing further increases in prices in these early months of the new season.

Among all agricultural commodities, dairy products have witnessed the largest gains compared with last year, ranging from 80 percent to more than 200 percent. Higher animal feed costs, tight dairy supplies following (1) the running down of inventories in the European Union and (2) drought in Australia, (3) the suspension of exports by some countries (4) coupled with the imposition of taxes by others, and (5) dynamic import demand are the main factors that have sustained dairy prices at historically high levels.

High feed prices have also raised costs for animal production and resulted in an increase in livestock prices; with poultry rising most, by at least 10 percent. In addition, growth in consumption and gradual reductions in trade restrictions are contributing to the increase in meat and poultry prices this season.

Convergence of factors

The persistent upward trend in international prices of most agricultural commodities since last year is only in part a reflection of a tightening in their own supplies. Global markets have become increasingly intertwined. As a result, linkages and spill-over effects from one market to another have greatly increased in recent years, not only among agricultural commodities, but across all commodities and between commodities and the financial sector.

Financial markets

Market-oriented policies are gradually making agricultural markets more transparent and, in the process, are elongating the financial opportunities for increased portfolio diversification and reduction in risk exposures. This is a development that is taking place just as financial markets around the world are experiencing the most rapid growth, driven by plentiful international liquidity. This abundance of liquidity reflects favourable economic performances around the world, notably among emerging economies, low interest rates and high petroleum prices:

energy :: sustainability :: biomass :: bioenergy :: biofuels :: food :: agricultural commodities :: petroleum :: drought :: speculation :: China :: India :: FAO ::

energy :: sustainability :: biomass :: bioenergy :: biofuels :: food :: agricultural commodities :: petroleum :: drought :: speculation :: China :: India :: FAO :: These developments have paved the way for massive amounts of cash becoming available for investment (by equity investors, funds, etc.) in markets that use financial instruments linked to the functioning of agricultural commodity markets (e.g. future and option markets). The buoyant financial markets are boosting asset allocation and drawing the attention of speculators to such markets, as a way of spreading their risk and pursuing of more lucrative returns. Such influx of liquidity is likely to influence the underlying spot markets to the extent that they affect the decisions of farmers, traders and processors of agricultural commodities. It seems more likely, though, that speculators contribute more to raising spot price volatility rather than their levels.

Soaring oil prices

Soaring petroleum prices have contributed to the increase in prices of most agricultural crops: by raising input costs, on the one hand, and by boosting demand for agricultural crops used as feedstock in the production of alternative energy sources (e.g. biofuels) on the other. National policies that aim to reduce greenhouse gas emissions are behind the fast growth of the biofuel industry.

Rising fossil fuel prices and attempts to reduce dependence on imported oil, however, have provided the extra incentive for many countries to opt for even more challenging crop production targets. The combination of high petroleum prices and the desire to address environmental issues is currently at the forefront of the rapid expansion of the biofuel sector: this is likely to boost demand for feedstocks, most notably, sugar, maize, rapeseed, soybean, palm oil and other oilcrops as well as wheat for many more years to come. However, much will also depend on the supply and demand fundamentals of the biofuel sector itself.

Freight rates

Freight rates have become a more important factor in agricultural markets than in the past. Increased fuel costs due to record oil prices, stretched shipping capacity, port congestion and longer trade routes have pushed up shipping costs. The Baltic Exchange Dry Index, a measure of shipping costs for bulk commodities such as grains and oilseeds, has recently passed the 10 000 mark for the first time with freight rates up more than 80 percent compared with the previous year. Not only have these record freight values increased the cost of transportation, but they have significant ramifications on the geographical pattern of trade, as many countries opt to source their import purchases from nearer suppliers to save on transport costs. In many instances, this development has also sparked a noticeable reduction in the degree of world market integration, with prices at regional or localized levels falling out of line with world levels.

Exchange rates

Exchange rate swings play a critical role in all markets and agricultural markets are no exception. Yet, rarely have currency developments been as important in shaping agricultural prices as in recent months. The gradual decline in the US dollar against most currencies since 2005 has made imports from the United States cheaper, thereby boosting demand for products that are exported from the United States. As international prices of most commodities are also primarily expressed in US dollar, this weakening of the dollar has helped push the United States export prices higher, exasperating the overall price strength, especially, in recent months, for wheat.

Evidently, the increases in the US dollar dominated prices of commodities affect international buyers (importers) differently, depending on how the value of their own currency changed vis-à-vis the US dollar. The fact that the dollar depreciated sharply against all major currencies lessens the true impact of the rise in world prices, a major reason behind the brisk world import demand that, in spite of high prices, shows very little sign of retreat or rationing.

Looking ahead

The main factor affecting the uncertainty in agricultural markets is how linkages with other markets, including markets of other agricultural commodities, will influence the direction and magnitude of price changes during the coming months and into the next season. This volatility in prices, especially in the case of agricultural crops, will represent a major hurdle in decision-making by farmers around the world.

Nowhere is this more evident than in the current debate about wheat plantings for next season. To most farmers, the current high wheat prices are only one reason to plant more wheat. The other is the general anticipation that even if wheat prices were to decline from their current high values, the decrease is expected to be less than those of other competing crops. In other words, farmers would be better off planting more land to wheat because of its higher relative profitability compared with other crops. In fact, all indications point to more wheat being planted around the world for harvesting next year. The recent decision by the European Union to release land from its set-aside programmes and the move by other major producing countries such as India to encourage farmers to grow more wheat by raising wheat procurement prices are also likely to pave the way for a much-needed rebound in world production in 2008.

All of the above, of course, assumes a normal weather situation, notwithstanding the fact that weather is impossible to predict. Prolonged drought in Australia, especially this year and last, affecting as it did a major wheat exporter, is a case in point. Yet, a strong expansion in wheat production, assuming normal growth in consumption, is bound to bring down wheat prices.

This brings about a critical issue: if more wheat gets planted, what will happen to the prices of other crops? Part of the answer can be found in what took place in the previous season with maize: once maize prices began to rise, plantings expanded across the world; jumping by 19 percent alone in the United States. Higher plantings and favourable weather drove maize production to a record this year, and this abundance started to push down prices, which are now well below their earlier highs, but still above levels of last year. Given a limited potential for expanding the agricultural frontier, the increase in maize plantings was at the expense of reductions in areas dedicated to several other crops, the production of which suffered as a result. A good example is soybeans and, to some extent, wheat and cotton. It is clear that by shifting land out of one crop into another, prices of those crops with reduced planting could increase.

Such trends have always existed and switching crops to maximize returns is nothing new. Most countries produce a host of crops and planting periods together with areas can be similar, making substitution easier. However, what makes recent episodes differ from the past is that inventories are being kept at low (almost pipeline) levels, which makes prices particularly sensitive to unexpected changes. In other words, agricultural markets, and food crops in particular, may be going through a period whereby stocks, especially those in major exporting countries, no longer play their traditional role as a buffer against sudden fluctuations in production and demand. This change has come about because of reduced government interventions associated with a general policy shift towards liberalizing agricultural commodity markets.

The role of farmers in this ever more populated world has never been more critical. It is one of FAO's key roles, at this key juncture, to help farmers in making the right decisions, by providing them with reliable and timely information about market and price trends.

Volatility in agricultural commodities

Volatility measures the degree of fluctuation in the price of a commodity that it experiences over a given time frame. Wide price movements over a short period of time typify the term ‘high volatility’. International prices for agricultural commodities are renowned for their high volatility, a feature which has been, and continues to be a cause for concern among governments, traders, producers and consumers. Many developing countries are still highly dependent on commodities, either in their export or import. While high price spikes can be a temporary boom to the export economy, they can also heighten the cost of importing foodstuffs and agricultural inputs. At the same time, large fluctuations in prices can have a destabilizing effect on real exchange rates of countries, putting a severe strain on their economic environment and hampering efforts to reduce poverty. In a prolonged volatile environment, the problem of extracting the true price signal from the noise may arise, a situation that can lead to an inefficient allocation of resources. Greater uncertainty limits opportunities for producers to access credit markets and tends to result in the adoption of low risk production technologies at the expense of innovation and entrepreneurship. In addition, the wider and more unpredictable price changes of a commodity are, the greater is the possibility of realizing large gains on speculating future price movements of that commodity. That is to say, volatility can attract significant speculative activity, which in turn can initiate a vicious cycle of destabilizing cash prices.

Volatility measures how much prices have moved or how they are expected to change. Historical volatility represents past price movements and reflects the resolution of supply and demand factors. It is often computed as the annualized standard deviation of the change in price. On the other hand, implied volatility represents the market’s expectation of how much the price of a commodity is likely to move in the future. The data upon which historical volatility is calculated may no longer be reflective of the prevailing or expected supply and demand situation. For this reason, implied volatility tends to be more responsive to current market conditions. It is called “implied” because, by dealing with future events, it cannot be observed, and can only be inferred from the price of an “option”.

An “option” gives the bearer the right to sell a commodity (put option) or buy a commodity (call option) at a specified price for a specified future delivery date. Options are just like any other commodity, and are priced based on the law of supply and demand. Any excess or deficit of demand would suggest that traders have different expectations of the future price of the underlying commodity. The more divergent these expectations are, the higher the implied volatility of the underlying commodity. Using the price of an option to estimate price volatility is analogous to using the future’s price to estimate the spot price at the future’s delivery date and location.

Does implied volatility matter? Prices that are observed today of commodities which are traded in the major global exchanges are in someway determined by movements in implied volatility, in that they convey all information, future and the present, pertinent to the market and the commodity. Hence, implied volatility as a metric is an important instrument used in the price discovery process and as a barometer as to where markets might be headed.

How has volatility evolved?

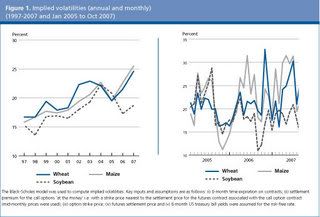

For wheat, maize and soybeans, the CBOT is widely regarded as the major centre for their price discovery. Implied volatilities during the past ten years for these commodities as well over the past 22 months are shown in the following figure.

Volatility for wheat and maize has been creeping up steadily over the course of the decade, while soybean volatility has been relatively flat (graph 3, click to enlarge). Moreover, it now appears more of a permanent feature in the grain markets than was the case in the past. A more detailed examination of the recent past reveals just how volatile grain markets have become and how volatility has been sustained. Since the beginning of 2006, wheat and maize implied volatility has frequently spiked to levels in the realm of 30 percent, and as of 11 October 2007, implied volatility stood at 27 and 22 percent for each commodity, respectively. How are these values interpreted?

These percentages are a measure of the standard deviation in the expected price six months ahead. Assuming that prices are normally distributed, the properties of the distribution can be used to say ‘the market estimates with 68 percent certainty that prices will rise or fall by 27 percent for wheat and 22 percent for maize’. In a similar vein, the likelihood that prices will exceed their current values by more than 50 percent in six months time is perceived to have a probability of around 2 percent, in other words quite unlikely. This is not to say that such events will not take place. The surge in maize prices that began in September 2006 surprised the markets, then, although traders were betting on higher prices, they handed only a 5 percent chance of a 50 percent or more increase in the price of maize in six months. Instead, prices actually climbed by almost 60 percent in that period. A one-off misjudgement? Apparently not. More recently, wheat traders were caught totally off-guard, when in April 2007 they were 99 percent certain that wheat prices would not rise by more than half their value, in six months, wheat prices had doubled. The large upswings in implied volatilities witnessed today, bear testimony to the enormous uncertainty that markets face in predicting how grain prices could evolve in the short term.

In the absence of readily available options data to estimate implied volatility for other commodities, historical volatilities were calculated, and for consistency, computations were also made for soybeans, wheat and maize. Classifying the latter with rice under ‘bulk commodities’, a similar picture to the above is portrayed. Wheat and maize price volatility has steadily risen over the past decade, peaking at over 30 percent in 2007. By contrast, volatility in the rice sector has moved sharply downwards, and in 2007 stood at just one-eighth of the variability in the grain sector.

Among the vegetable oils, volatility has been fairly even since 1982 for all the products, but there appears some resurgence in the prices of palm, sunflower and rapeseed oil. The upturn in volatility for dairy product prices has been most striking, rising almost four-fold since 2005 in the case of butter. By contrast, price changes in meat products have been in a state of quiescence over the past two years. Similarly volatility for many raw materials, traditionally the highest of all agricultural commodities, has steadily fallen, but for sugar and tea, from the peaks of the previous year (graph 4, click to enlarge).

Volatility is an important property in understanding the tendency for a commodity to undergo price changes. More volatile commodities undergo larger and more frequent price changes. Implied volatility can be a useful metric in revealing how traders expect prices to evolve in the shorter term. However, given the huge upheaval in grain markets over the past year or so, it also exposes just how wrong expectations can be.

References:

FAO: FAO forecasts continued high cereal prices - Unfavourable weather, low stocks, tight supplies amid strong demand cited as causes - November 7, 2007.

FAO: Food Outlook - Global Market Analysis 2007 - November 7, 2007.

--------------

--------------

Mascoma Corporation, a cellulosic ethanol company, today announced the acquisition of Celsys BioFuels, Inc. Celsys BioFuels was formed in 2006 to commercialize cellulosic ethanol production technology developed in the Laboratory of Renewable Resources Engineering at Purdue University. The Celsys technology is based on proprietary pretreatment processes for multiple biomass feedstocks, including corn fiber and distiller grains. The technology was developed by Dr. Michael Ladisch, an internationally known leader in the field of renewable fuels and cellulosic biofuels. He will be taking a two-year leave of absence from Purdue University to join Mascoma as the company’s Chief Technology Officer.

Mascoma Corporation, a cellulosic ethanol company, today announced the acquisition of Celsys BioFuels, Inc. Celsys BioFuels was formed in 2006 to commercialize cellulosic ethanol production technology developed in the Laboratory of Renewable Resources Engineering at Purdue University. The Celsys technology is based on proprietary pretreatment processes for multiple biomass feedstocks, including corn fiber and distiller grains. The technology was developed by Dr. Michael Ladisch, an internationally known leader in the field of renewable fuels and cellulosic biofuels. He will be taking a two-year leave of absence from Purdue University to join Mascoma as the company’s Chief Technology Officer.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Links to this post:

Create a Link

<< Home