Environmental researchers propose radical 'human-centric' map of the world

Ecologists pay too much attention to increasingly rare 'pristine' ecosystems while ignoring the overwhelming influence of humans on the environment, say researchers from McGill University and the University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC). Therefor they propose a radical 'anthropocentric' view on ecology. This new model of the biosphere moves us away from an outdated and romantic view of the world as "natural ecosystems with humans disturbing them" - a vision often found amongst environmentalists and activist - and towards a realistic vision of "human systems with natural ecosystems embedded within them". This is a major change in perspective but it is critical for sustainable management of our biosphere in the 21st century.

Professor Erle Ellis of UMBC and Professor Navin Ramankutty of McGill assert that the current system of classifying ecosystems into biomes (or 'ecological communities') like tropical rainforests, grasslands and deserts may be misleading because humans have become the ultimate ecosystem engineers. To take this into account, they propose an entirely new model of human-centered 'anthropegenic' biomes in the November 19 issue of the journal Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment.

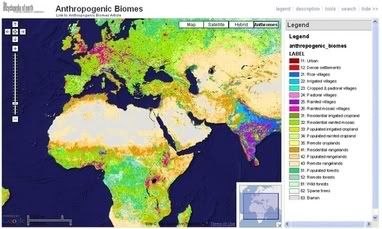

For their part, Ellis and Ramankutty propose a radically new system of anthropogenic biomes - dubbed 'anthromes' - which describe globally-significant ecological patterns within the terrestrial biosphere caused by sustained direct human interaction with ecosystems, including agriculture, urbanization, forestry and other land uses. Now that humans have fundamentally altered global patterns of ecosystem form, process, and biodiversity, anthropogenic biomes provide a more contemporary view of the terrestrial biosphere in its human-altered form (map, click to enlarge; you can view the 'anthromes' in Google Earth, Google Maps and Microsoft Virtual Earth here.)

Humans have become ecosystem engineers, routinely reshaping ecosystem form and process using tools and technologies, such as fire, dams, irrigation or plantation, that are beyond the capacity of any other organism:

energy :: biomass :: bioenergy :: biofuels :: ecology :: biosphere :: biomes :: anthromes :: anthropocentric :: sustainability :: realism :: romanticism ::

energy :: biomass :: bioenergy :: biofuels :: ecology :: biosphere :: biomes :: anthromes :: anthropocentric :: sustainability :: realism :: romanticism ::

This exceptional capacity for ecosystem engineering, expressed in the form of agriculture, forestry, industry and other activities, has helped to sustain unprecedented population growth, such that humans now consume about one third of all terrestrial net primary production, move more earth and produce more reactive nitrogen than all other terrestrial processes combined, and are causing global extinctions and changes in climate that are comparable to any observed in the natural record.

Clearly, humans are now a force of nature rivaling climate and geology in shaping the terrestrial biosphere and its processes. As a result, the vegetation forms predicted by conventional biome systems are now rarely observed across large areas of Earth's land surface.

If we want to think about going into a sustainable future and restoring ecosystems, we have to accept that humans are here to stay. Humans are part of the package, and any restoration has to include human activities in it. Man has become a 'geo-engineer' with often catastrophic consequences for nature. But his unsurpassed capacity to manage ecosystems also holds the key to utilizing these systems in a sustainable way.

Maps and classes

Viewing a global map of anthropogenic biomes shows clearly the inextricable intermingling of human and natural systems almost everywhere on Earth's terrestrial surface, demonstrating that interactions between these systems can no longer be avoided in any significant way.

Anthropogenic biomes are not simple vegetation categories, and are best characterized as heterogeneous landscape mosaics combining a variety of different land uses and land covers. Urban areas are embedded within agricultural land, trees are interspersed with croplands and housing, and managed vegetation is mixed with semi-natural vegetation (e.g. croplands are embedded within rangelands and forests).

For example, Croplands biomes are mostly mosaics of cultivated land mixed with trees and pastures, and therefore possess just slightly more than half of the world's total crop-covered area (8 of 15 million km2), with most of the remaining cultivated area found in Village (~25%) and Rangeland (~15%) biomes. While Forested biomes are host to a greater extent of Earth's tree-covered land, about a quarter of Earth's tree cover was found in Croplands biomes, a greater extent than that found in Wild forests (~20%).

Romanticism versus realism

Part of the enduring fascination for 'virgin' ecosystems stems from a romantic, eurocentric view of nature. Environmentalists and activists often draw on this vision, with at times truly perverse effects: the people who actively work and live in these 'pristine' natural environments are sometimes reduced, idealised and 'naturalised' to the status of people living in 'perfect harmony' with nature, like other species. When these 'indigenous' people break the romantic vision projected onto them, environmentalists tend to look at them as destructive forces and 'enemies'. And there the debate often ends.

The new, radically human-centric view on ecology reopens these debates and offers a space for negotiation that may allow stakeholders to transform their often antagonistic relationship into one of a dialogue based on realism instead of romanticism.

Sustainable ecosystem management must develop and maintain beneficial interactions between managed and natural systems: avoiding these interactions by simply negating them is no longer a practical strategy. Though still at an early stage of development, anthropogenic biomes offer a framework for incorporating humans directly into realistic models and investigations of the terrestrial biosphere and its changes, providing an essential foundation for ecological research in the 21st century.

References:

Ellis, Erle and Navin Ramankutty, "Putting people in the map: anthropogenic biomes of the world", Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, November 26, 2007, DOI: 10.1890/070062

Ellis, Erle and Navin Ramankutty; Mark McGinley (Topic Editor). 2007. "Anthropogenic biomes." In: Encyclopedia of Earth. Eds. Cutler J. Cleveland (Washington, D.C.: Environmental Information Coalition, National Council for Science and the Environment). [Published in the Encyclopedia of Earth November 26, 2007; Retrieved November 26, 2007]

View the biomes in Google Earth, Google Maps and Microsoft Virtual Earth.

Professor Erle Ellis of UMBC and Professor Navin Ramankutty of McGill assert that the current system of classifying ecosystems into biomes (or 'ecological communities') like tropical rainforests, grasslands and deserts may be misleading because humans have become the ultimate ecosystem engineers. To take this into account, they propose an entirely new model of human-centered 'anthropegenic' biomes in the November 19 issue of the journal Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment.

Ecologists go to remote parts of the planet to study pristine ecosystems, but no one studies it in their back yard. It's time to start putting instrumentation in our back yards - both literal and metaphorical - to study what's going on there in terms of ecosystem functioning. - Navin Ramankutty, Department of Geography, Earth System Science Program, McGill University.Existing biome classification systems are based on natural-world factors such as plant structures, leaf types, plant spacing and climate. The Bailey System, developed in the 1970's, divides North America into four climate-based biomes: polar, humid temperate, dry and humid tropical. The World Wildlife Fund (WWF) ecological land classification system identifies 14 major biomes, including tundra, boreal forests, temperate coniferous forests and deserts and xeric shrublands.

For their part, Ellis and Ramankutty propose a radically new system of anthropogenic biomes - dubbed 'anthromes' - which describe globally-significant ecological patterns within the terrestrial biosphere caused by sustained direct human interaction with ecosystems, including agriculture, urbanization, forestry and other land uses. Now that humans have fundamentally altered global patterns of ecosystem form, process, and biodiversity, anthropogenic biomes provide a more contemporary view of the terrestrial biosphere in its human-altered form (map, click to enlarge; you can view the 'anthromes' in Google Earth, Google Maps and Microsoft Virtual Earth here.)

Humans have become ecosystem engineers, routinely reshaping ecosystem form and process using tools and technologies, such as fire, dams, irrigation or plantation, that are beyond the capacity of any other organism:

energy :: biomass :: bioenergy :: biofuels :: ecology :: biosphere :: biomes :: anthromes :: anthropocentric :: sustainability :: realism :: romanticism ::

energy :: biomass :: bioenergy :: biofuels :: ecology :: biosphere :: biomes :: anthromes :: anthropocentric :: sustainability :: realism :: romanticism :: This exceptional capacity for ecosystem engineering, expressed in the form of agriculture, forestry, industry and other activities, has helped to sustain unprecedented population growth, such that humans now consume about one third of all terrestrial net primary production, move more earth and produce more reactive nitrogen than all other terrestrial processes combined, and are causing global extinctions and changes in climate that are comparable to any observed in the natural record.

Clearly, humans are now a force of nature rivaling climate and geology in shaping the terrestrial biosphere and its processes. As a result, the vegetation forms predicted by conventional biome systems are now rarely observed across large areas of Earth's land surface.

Over the last million years, we have had glacial-interglacial cycles, with enormous changes in climate and massive shifts in ecosystems. The human influence on the planet today is almost on the same scale. Nearly 30 to 40% of the world's land surface today is used just for growing food and grazing animals to serve the human population. - Navin RamankuttyThe researchers argue human land-use practices have fundamentally altered the planet. Their analysis was quite surprising, said Ramankutty. Less than a quarter of Earth's ice-free land is wild and 'pristine', and only 20% of this is forests; more than 36% is barren, such that Earth's remaining wildlands account for only about 10% of global net primary production. More than 80% of all people live in the densely populated urban and village biomes that cover approximately 8% of global ice-free land. Agricultural villages are the most extensive of all densely populated biomes; one in four people lives within them. Ramankutty concludes that when one is studying a 'pristine' landscape, one is really only studying about 20% of the world.

If we want to think about going into a sustainable future and restoring ecosystems, we have to accept that humans are here to stay. Humans are part of the package, and any restoration has to include human activities in it. Man has become a 'geo-engineer' with often catastrophic consequences for nature. But his unsurpassed capacity to manage ecosystems also holds the key to utilizing these systems in a sustainable way.

Maps and classes

Viewing a global map of anthropogenic biomes shows clearly the inextricable intermingling of human and natural systems almost everywhere on Earth's terrestrial surface, demonstrating that interactions between these systems can no longer be avoided in any significant way.

Anthropogenic biomes are not simple vegetation categories, and are best characterized as heterogeneous landscape mosaics combining a variety of different land uses and land covers. Urban areas are embedded within agricultural land, trees are interspersed with croplands and housing, and managed vegetation is mixed with semi-natural vegetation (e.g. croplands are embedded within rangelands and forests).

For example, Croplands biomes are mostly mosaics of cultivated land mixed with trees and pastures, and therefore possess just slightly more than half of the world's total crop-covered area (8 of 15 million km2), with most of the remaining cultivated area found in Village (~25%) and Rangeland (~15%) biomes. While Forested biomes are host to a greater extent of Earth's tree-covered land, about a quarter of Earth's tree cover was found in Croplands biomes, a greater extent than that found in Wild forests (~20%).

Romanticism versus realism

Part of the enduring fascination for 'virgin' ecosystems stems from a romantic, eurocentric view of nature. Environmentalists and activists often draw on this vision, with at times truly perverse effects: the people who actively work and live in these 'pristine' natural environments are sometimes reduced, idealised and 'naturalised' to the status of people living in 'perfect harmony' with nature, like other species. When these 'indigenous' people break the romantic vision projected onto them, environmentalists tend to look at them as destructive forces and 'enemies'. And there the debate often ends.

The new, radically human-centric view on ecology reopens these debates and offers a space for negotiation that may allow stakeholders to transform their often antagonistic relationship into one of a dialogue based on realism instead of romanticism.

Sustainable ecosystem management must develop and maintain beneficial interactions between managed and natural systems: avoiding these interactions by simply negating them is no longer a practical strategy. Though still at an early stage of development, anthropogenic biomes offer a framework for incorporating humans directly into realistic models and investigations of the terrestrial biosphere and its changes, providing an essential foundation for ecological research in the 21st century.

References:

Ellis, Erle and Navin Ramankutty, "Putting people in the map: anthropogenic biomes of the world", Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, November 26, 2007, DOI: 10.1890/070062

Ellis, Erle and Navin Ramankutty; Mark McGinley (Topic Editor). 2007. "Anthropogenic biomes." In: Encyclopedia of Earth. Eds. Cutler J. Cleveland (Washington, D.C.: Environmental Information Coalition, National Council for Science and the Environment). [Published in the Encyclopedia of Earth November 26, 2007; Retrieved November 26, 2007]

View the biomes in Google Earth, Google Maps and Microsoft Virtual Earth.

--------------

--------------

SRI Consulting released a report on chemicals from biomass. The analysis highlights six major contributing sources of green and renewable chemicals: increasing production of biofuels will yield increasing amounts of biofuels by-products; partial decomposition of certain biomass fractions can yield organic chemicals or feedstocks for the manufacture of various chemicals; forestry has been and will continue to be a source of pine chemicals; evolving fermentation technology and new substrates will also produce an increasing number of chemicals.

SRI Consulting released a report on chemicals from biomass. The analysis highlights six major contributing sources of green and renewable chemicals: increasing production of biofuels will yield increasing amounts of biofuels by-products; partial decomposition of certain biomass fractions can yield organic chemicals or feedstocks for the manufacture of various chemicals; forestry has been and will continue to be a source of pine chemicals; evolving fermentation technology and new substrates will also produce an increasing number of chemicals.

1 Comments:

Opinion: Monopolies Are Not Good for the Environment

Availability of Sustainable Wood Products Hampered by Certification from Forest Stewardship Council

Exclusivity Drives Up Prices and Steers Builders to turn to Petroleum Products and Other Non-renewable Resources.

FSC Exclusivity Could ‘LEED’ to Other Environmental Problems

Long before people in the “new world” began to understand the risks of dwindling timber supplies, European countries saw first-hand the potential danger of over harvesting.

From Germany’s proactive, 18th-century commitment to renewable forestry, to England’s reforestation efforts in the wake of the Industrial Revolution, many countries learned these lessons well.

In this tradition, The Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification schemes (PEFC) was founded in 1999. Stemming from the rich, long-time traditions of sustainable forestry in Europe, PEFC has grown to impressive, global proportions. Today, the Sustainable Forest Management criteria it uses are supported by 149 governments worldwide, covering 85% of the world’s forest area.

PEFC respects and integrates each country’s forestry practices, using a structure that works in tandem with local governments, stakeholders, cultures and traditions. Yet, in some circles, the PEFC and its European roots are inexplicably frowned upon.

For instance, in today’s “green” building movement, the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) rating system is the most successful such program in the world. Administered by the U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC), the LEED system is now in use in more that 14,000 construction projects in 30 countries, including all 50 United States.

However, lumber used for LEED construction projects must be certified by just one entity—the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC).

As the demand for green, renewable resources continues to grow, why does LEED insist on this exclusive arrangement with a single certification scheme?

Both the FSC and the PEFC use independent third-party certification, providing abundant reassurance that the wood originates from sustainably managed forests. They include oversight by all vital stakeholders—member countries, non-governmental organizations, landowners, social groups and others.

Within each group’s framework, the national governing bodies from individual countries and regions develop standards with substantial opportunity for public review. And both provide clear chain-of-custody tracking and labeling that assure end users of legal and environmentally sound harvesting.

One independent industry consultant showed how the PEFC even goes beyond FSC standards when it comes to conformity with a number of ISO certification and accreditation guides.

This FSC-LEED exclusivity is especially baffling when you remember that PEFC certification represents about two thirds of all certified forests globally, which in all account for about a quarter of the global industrial roundwood production.

Additionally, many FSC certified acres are owned by governments or families focused on preservation—they have no intention to harvest for building-material production. And available FSC-certified veneers are often just a fraction of the number of veneers available through the other certification schemes.

It’s clear that accepting PEFC certified wood products would open a tremendous new resource-pool for the green building movement.

Here in North America, leading national forest certification programs, such as the Canadian Standards Association (CSA), and the Sustainable Forestry Initiative (SFI)—both part of the PEFC—create a central source for certified timber for North America. Combined, CSA and SFI certify more than 328 million acres of sustainable forestland in North America, versus about 69 million total acres certified by the FSC.

Limiting the availability of sustainable wood products drives up prices, prompting more builders to turn to materials derived from petroleum products and other non-renewable resources. Or they turn to concrete and other materials that require significantly more energy to produce, ultimately increasing greenhouse gas emissions and leaving a bigger carbon footprint.

Left unaddressed, all of these issues could lead to further environmental damage, something that I’m sure all of us—LEED and the FSC included—would like to prevent. LEED’s acceptance of PEFC certified lumber would be a significant step in the right direction for greater, worldwide adoption of green building practices.

# # #

Company Contact:

Doug Martin

Pollmeier Inc.

Portland, OR 97223

Phone: 503-452-5800

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.pollmeier.com

Post a Comment

Links to this post:

Create a Link

<< Home