African countries begin to recognize their vast biofuels potential

Reporters from the Deutsche Presse-Agentur (DPA) have visited African countries to see how they are positioning themselves in the biofuels debate. Visitors to the poor south-east African country of Mozambique are often taken aback at the cost of getting around, they write. "Petrol is the problem," taxi drivers in the capital Maputo retort when challenged over fares that begin at 100 meticais (close to 4 dollars) for a journey of no more than a couple of blocks.

Spiralling oil prices, which have resulted in a more than three-fold jump in fuel prices in Mozambique this year, are one factor fuelling the scramble among African countries with no reserves of 'black gold' to corner the market for greener alternatives. High oil prices have catastrophic effects on energy intensive developing countries (earlier post), but biofuels may mitigate some of these disastrous impacts.

From Mali to Madagascar, Senegal to South Africa, biofuels is the buzzword as African countries wake up to the possibility of using their vast land resources to grow crops that reduce their fossil fuel bill.

Some NGOs from the West, like Oxfam, have warned against land in developing countries being gobbled up by sprawling biofuels plantations. But Africans themselves, like Mozambique's director for 'new and renewable energy', Antonio Saide, rebuff those concerns: "We have enough land for enough food." And indeed, many of the sceptical NGOs do not take into account that Africa has vast unused land resources on which energy crops can be grown sustainably.

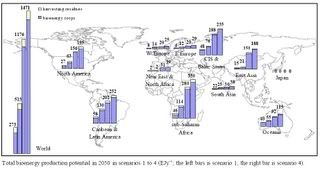

Projections by the International Energy Agency's Bioenergy Task forces show the continent can grow around 350EJ of bioenergy by 2050 in a high scenario, after the rising food, fiber and fodder needs for growing populations and livestock have been met, and under a 'no-deforestation' scenario. 300EJ is equivalent to twice the amount of the entire world's current petroleum consumption (see map, click to enlarge).

According to the UN's FAO, the effort could bring a rural renaissance and combat poverty and hunger in Africa. The Global South's staunchest biofuels proponent, Brazil's president Lula, sees bioenergy as more than just a weapon to fight poverty: it is a way to boost the sovereignty and economic independence of developing countries.

Biofuels carry the promise of much sought after foreign exchange as industrialized countries look to bioethanol and biodiesel to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions from transport. The European Union has decreed that 10 per cent of motor fuel used within its 27 member states must be biofuel by 2020. But European farmers have been slow to convert their operations from food to fuel crops leading EU officials to estimate they will have to import at least one-fifth of their biofuel needs. The world's largest emitter of greenhouse gases, the United States, has also announced plans to reduce its carbon footprint by increasing the use of renewable and alternative fuels nearly five-fold over the next 10 years.

These commitments are music to the ears of poor African countries that account for only a tiny proportion of global greenhouse gas emissions but are expected to be hardest hit by climate change, through increased flooding and drought.

A biofuel superpower in the making is how the vast former Portuguese colony of Mozambique is being talked up, where millions of hectares of unused land have been identified as suitable for the production of fuel crops. Some 700 million dollars has already been committed to biofuel production in Mozambique, including 510 million dollars from British-based Central Africa Mining and Exploration Company to produce ethanol from sugarcane in southern Gaza province.

The state has also received requests to open up more than 5 million hectares of land for the production of biodiesel, with coconuts, sunflowers and the weed-like jatropha plant being tested as possible feedstock. While energy independence is the primary goal, the small size of Mozambique's economy means that domestic energy needs could be quickly met by biofuels, Antonio Saide said. "We can very quickly satisfy the domestic market and begin to export," said Saide:

ethanol :: biodiesel :: biobutanol :: biomass :: bioenergy :: biofuels :: energy :: sustainability :: Africa ::

ethanol :: biodiesel :: biobutanol :: biomass :: bioenergy :: biofuels :: energy :: sustainability :: Africa ::

Another African country with big plans for biofuels is Senegal, whose President Abdoulaye Wade has enthused about an African "biofuels revolution" and placed fuel crops at the heart of an agriculture renewal programme focussing on small farmers.

Not to be outdone African powerhouse South Africa is also preparing to plough money into biofuels, with construction already underway on one out of eight planned maize-to-ethanol refineries.

These Johnny-come-latelys in a biofuels industry dominated by Brazil have a number of aces up their sleeve. Many are United Nations Least Developed Countries that enjoy tariff-free access to the EU for their goods under the Everything But Arms initiative. The US African Growth and Opportunity Act also gives African countries preferential access to the US for a number of goods, that could be extended to include biofuels.

But growing fuel instead of food crops on a continent that is plagued by food insecurity has had its critics. Mindful of these concerns, drought-prone countries like Mozambique, Swaziland, Zambia, Madagascar and Mali are championing jatropha as a non-edible bio-oil plant that grows in almost any soil.

"Life-changing," was the verdict of rock star turned anti-poverty campaigner Bob Geldof on a jatropha plantation employing hundreds of workers in southern Swaziland, although questions remain around the plant's yield in sub-optimal conditions and the toxicity of its seeds.

Map: World's sustainable bioenergy potential by 2050 under four scenarios. Credit: IEA Bioenergy Task 40.

References:

Deutsche-Presse Agentur: Africa's big plans for biofuels - November 6, 2007.

IEA Bioenergy Task 40: Quickscan bio-energy potentials to 2050.

Spiralling oil prices, which have resulted in a more than three-fold jump in fuel prices in Mozambique this year, are one factor fuelling the scramble among African countries with no reserves of 'black gold' to corner the market for greener alternatives. High oil prices have catastrophic effects on energy intensive developing countries (earlier post), but biofuels may mitigate some of these disastrous impacts.

From Mali to Madagascar, Senegal to South Africa, biofuels is the buzzword as African countries wake up to the possibility of using their vast land resources to grow crops that reduce their fossil fuel bill.

Some NGOs from the West, like Oxfam, have warned against land in developing countries being gobbled up by sprawling biofuels plantations. But Africans themselves, like Mozambique's director for 'new and renewable energy', Antonio Saide, rebuff those concerns: "We have enough land for enough food." And indeed, many of the sceptical NGOs do not take into account that Africa has vast unused land resources on which energy crops can be grown sustainably.

Projections by the International Energy Agency's Bioenergy Task forces show the continent can grow around 350EJ of bioenergy by 2050 in a high scenario, after the rising food, fiber and fodder needs for growing populations and livestock have been met, and under a 'no-deforestation' scenario. 300EJ is equivalent to twice the amount of the entire world's current petroleum consumption (see map, click to enlarge).

According to the UN's FAO, the effort could bring a rural renaissance and combat poverty and hunger in Africa. The Global South's staunchest biofuels proponent, Brazil's president Lula, sees bioenergy as more than just a weapon to fight poverty: it is a way to boost the sovereignty and economic independence of developing countries.

Biofuels carry the promise of much sought after foreign exchange as industrialized countries look to bioethanol and biodiesel to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions from transport. The European Union has decreed that 10 per cent of motor fuel used within its 27 member states must be biofuel by 2020. But European farmers have been slow to convert their operations from food to fuel crops leading EU officials to estimate they will have to import at least one-fifth of their biofuel needs. The world's largest emitter of greenhouse gases, the United States, has also announced plans to reduce its carbon footprint by increasing the use of renewable and alternative fuels nearly five-fold over the next 10 years.

These commitments are music to the ears of poor African countries that account for only a tiny proportion of global greenhouse gas emissions but are expected to be hardest hit by climate change, through increased flooding and drought.

A biofuel superpower in the making is how the vast former Portuguese colony of Mozambique is being talked up, where millions of hectares of unused land have been identified as suitable for the production of fuel crops. Some 700 million dollars has already been committed to biofuel production in Mozambique, including 510 million dollars from British-based Central Africa Mining and Exploration Company to produce ethanol from sugarcane in southern Gaza province.

The state has also received requests to open up more than 5 million hectares of land for the production of biodiesel, with coconuts, sunflowers and the weed-like jatropha plant being tested as possible feedstock. While energy independence is the primary goal, the small size of Mozambique's economy means that domestic energy needs could be quickly met by biofuels, Antonio Saide said. "We can very quickly satisfy the domestic market and begin to export," said Saide:

ethanol :: biodiesel :: biobutanol :: biomass :: bioenergy :: biofuels :: energy :: sustainability :: Africa ::

ethanol :: biodiesel :: biobutanol :: biomass :: bioenergy :: biofuels :: energy :: sustainability :: Africa :: Another African country with big plans for biofuels is Senegal, whose President Abdoulaye Wade has enthused about an African "biofuels revolution" and placed fuel crops at the heart of an agriculture renewal programme focussing on small farmers.

Not to be outdone African powerhouse South Africa is also preparing to plough money into biofuels, with construction already underway on one out of eight planned maize-to-ethanol refineries.

These Johnny-come-latelys in a biofuels industry dominated by Brazil have a number of aces up their sleeve. Many are United Nations Least Developed Countries that enjoy tariff-free access to the EU for their goods under the Everything But Arms initiative. The US African Growth and Opportunity Act also gives African countries preferential access to the US for a number of goods, that could be extended to include biofuels.

But growing fuel instead of food crops on a continent that is plagued by food insecurity has had its critics. Mindful of these concerns, drought-prone countries like Mozambique, Swaziland, Zambia, Madagascar and Mali are championing jatropha as a non-edible bio-oil plant that grows in almost any soil.

"Life-changing," was the verdict of rock star turned anti-poverty campaigner Bob Geldof on a jatropha plantation employing hundreds of workers in southern Swaziland, although questions remain around the plant's yield in sub-optimal conditions and the toxicity of its seeds.

Map: World's sustainable bioenergy potential by 2050 under four scenarios. Credit: IEA Bioenergy Task 40.

References:

Deutsche-Presse Agentur: Africa's big plans for biofuels - November 6, 2007.

IEA Bioenergy Task 40: Quickscan bio-energy potentials to 2050.

--------------

--------------

A new Agency to manage Britain's commitment to biofuels was established today by Transport Secretary Ruth Kelly. The Renewable Fuels Agency will be responsible for the day to day running of the Renewable Transport Fuels Obligation, coming into force in April next year. By 2010, the Obligation will mean that 5% of all the fuels sold in the UK should come from biofuels, which could save 2.6m to 3m tonnes of carbon dioxide a year.

A new Agency to manage Britain's commitment to biofuels was established today by Transport Secretary Ruth Kelly. The Renewable Fuels Agency will be responsible for the day to day running of the Renewable Transport Fuels Obligation, coming into force in April next year. By 2010, the Obligation will mean that 5% of all the fuels sold in the UK should come from biofuels, which could save 2.6m to 3m tonnes of carbon dioxide a year.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Links to this post:

Create a Link

<< Home