USDA report looks at ethanol logistics and transportation

The Agricultural Marketing Department (AMD) of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) released a report which looks at the transportation requirements needed to sustain the rapidly growing corn-based ethanol sector. Trains, barges and trucks ship grains, ethanol and byproducts from the corn belt in the center of the country to America's coastal cities. In the future, dedicated pipelines may move the biofuel. In 'Expansion of U.S. Corn-based Ethanol from the Agricultural Transportation Perspective' [*.pdf] the question is raised which effects the growing production of ethanol will have on agricultural and ethanol transportation chains (see image for a schematic overview of the rail and truck ethanol distribution system).

The Agricultural Marketing Department (AMD) of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) released a report which looks at the transportation requirements needed to sustain the rapidly growing corn-based ethanol sector. Trains, barges and trucks ship grains, ethanol and byproducts from the corn belt in the center of the country to America's coastal cities. In the future, dedicated pipelines may move the biofuel. In 'Expansion of U.S. Corn-based Ethanol from the Agricultural Transportation Perspective' [*.pdf] the question is raised which effects the growing production of ethanol will have on agricultural and ethanol transportation chains (see image for a schematic overview of the rail and truck ethanol distribution system).For the first 6 months of 2007, U.S. ethanol production totaled nearly 3 billion gallons, 32 percent higher than the same period last year and ahead of USDA projections. As of August 29, there were 128 ethanol plants with annual production capacity totaling 6.78 billion gallons, and an additional 85 plants were under construction. U.S. ethanol production capacity is expanding rapidly and is currently expected to exceed 13 billion gallons per year by early 2009, if not sooner.

Ethanol demand has increased corn prices and led to expanded corn production, which is affecting grain transportation as corn use shifts from exports and feed use to ethanol production. Most ethanol is currently produced in the country's heartland, but 80 percent of the U.S. population (and therefore implied ethanol demand) lives along its coastlines (map, click to enlarge). Transportation factors to consider as ethanol production continues to expand therefor include:

Ethanol demand has increased corn prices and led to expanded corn production, which is affecting grain transportation as corn use shifts from exports and feed use to ethanol production. Most ethanol is currently produced in the country's heartland, but 80 percent of the U.S. population (and therefore implied ethanol demand) lives along its coastlines (map, click to enlarge). Transportation factors to consider as ethanol production continues to expand therefor include:- The capacity of the transportation system to move ethanol, feedstock, and co-products produced from ethanol

- The availability of corn close to ethanol plants (~ 50 miles)

- The location of feedlots relative to ethanol producing areas

AMS applied its modal share analysis to the three USDA scenarios: baseline (February 2007 long-term projections) and the two scenarios described above to evaluate the impact of ethanol production expansion on grain transportation. The 5-year 2000-2004 modal share rates were assumed to stay constant over the projected period:

energy :: sustainability :: biomass :: bioenergy :: biofuels :: ethanol :: corn :: transportation :: logistics ::

energy :: sustainability :: biomass :: bioenergy :: biofuels :: ethanol :: corn :: transportation :: logistics :: Agricultural transportation and ethanol

Rapid expansion of the U.S. ethanol industry could have several implications for agricultural transportation, including increasing volumes of ethanol shipments and shifting grain and oilseed marketing patterns that could occur due to changes in production and use.

Transportation is typically the third highest expense to an ethanol producer—after feedstock and energy. Balancing transportation operating expenses with fixed infrastructure costs can be critical to sustained profitability for each ethanol plant.

Storage needs for ethanol are also related to transportation needs—truck and rail have a faster turnaround and barges can haul larger quantities. For example, trucks offer more flexibility and responsiveness to move the product as the market dictates, reducing storage needs at the ethanol plant. But, barge may offer cost savings due to volumes moved.

Other transportation requirements include inbound feedstock and outbound co-products. Corn is shipped to the plant as feedstock (mostly by truck) and distillers grains (dry distillers grains with solubles (DDGS) and wet distillers grains (WDGs)) are shipped by truck, rail, or barge.

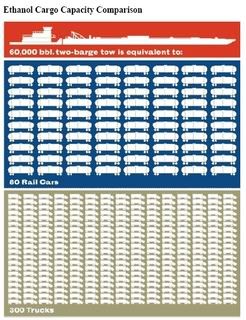

For purposes of comparison, a large petroleum 2-barge unit tow hauls 2.52 million gallons (although ethanol is usually shipped in smaller, 630,000-gallon tanker barges), which is equivalent to about 80 railcars or 300 tanker trailers (table, click to enlarge).

In 2005, rail was the primary transportation mode for ethanol, shipping 60 percent of ethanol production—approximately 2.9 billion gallons of ethanol; followed by trucks—30 percent, and barges—10 percent (graph, click to enlarge).

In 2005, rail was the primary transportation mode for ethanol, shipping 60 percent of ethanol production—approximately 2.9 billion gallons of ethanol; followed by trucks—30 percent, and barges—10 percent (graph, click to enlarge).Ethanol transactions currently involve two types of marketing arrangements: 1) direct sales to customers and 2) movements to a strategic location. Both types of arrangements require transportation. Movement of the product can be arranged by the customer, supplier, or a third party—known in the petroleum industry as the marketer.

As the number of companies producing ethanol increases, the share of ethanol marketed by third parties—marketers—is expected to rise as well. The marketers ensure supply interruptions are kept to a minimum and are able to move large volumes by gathering production from several smaller ethanol plants into unit trains (trains consisting of 85–100 cars that stay together from origin to destination). The role of the regional (shortline) railroads has increased for the shorter movements of ethanol to intermediate rail terminals. As ethanol volumes rise, the industry may start requiring quality control programs that ensure that shipments are not contaminated with other chemicals.

Ethanol producers are expected to continue to rely on qualified ethanol marketers to efficiently distribute their products. Some railroads have instituted a Certificate of Authenticity program that certifies ethanol quality shipments on their railroad.

Transportation sensitivity to demand and distribution changes

All three modes used to transport ethanol—rail, barge, and truck—are at or near capacity. Total rail freight is forecast to increase from 1,879 million tons in 2002 to 3,525 million tons by 2035, an increase of nearly 88 percent.6 Federal Highway Administration projects truck freight to almost double from 2002 to 2020, and driver shortages are projected to reach 219,000 by 2015.

In 2004, there were 1.3 million long-haul heavy-duty truck drivers. The lock and dam system on the inland waterways is aging. The lack of excess transportation capacity increases the sensitivity of transportation to sudden changes in transportation demand and distribution patterns. Changes in these patterns brought on by rapidly increasing ethanol production could impact rail network performance, highway congestion, and barge traffic. For example, the increased sensitivity of transportation modes became evident in the aftermath of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita in 2005, when rail had insufficient capacity to transport displaced grain barge freight and trucks could not carry the grain economically for long distances.

To date, logistical concerns have not hampered ethanol production growth or the construction and expansion of new ethanol plants. However, issues that may arise as production grows include:

- Uncertainty about the location of and demand from terminal markets which consolidate, transload, and distribute ethanol for blending. Change in State policies towards ethanol may decrease this uncertainty.

- Shifts in transportation demand for corn, ethanol, DDGS, and WDGs among rail, truck, and barge, in the context of overall traffic and future ethanol production locations.

- Concern about the adequacy of transportation infrastructure to efficiently ship ethanol and co-products.

- Increased transportation demand for agricultural inputs, mainly additional fertilizer for increased corn acreage.

Ethanol production scenarios and transportation

The increased use of corn for ethanol has raised corn prices, and has resulted in increased corn production in the United States and changes in grain transportation as corn use shifts from exports and feed use to ethanol production. In August, USDA forecast corn production for the 2007/08 marketing year to reach about 13.05 billion bushels, up 2.5 billion bushels (24 percent) from last year.

Increased grain production typically causes transportation demand to increase. Rapid ethanol production expansion, however, may affect where corn is transported and by which transportation mode. For example:

- Much of the increase in the corn crop will be trucked to ethanol facilities. Trucks currently dominate the local transportation of corn to ethanol plants. Should this trend continue, it may lead to a shift in modal share of grain transportation. However, as corn production is expected to continue to increase, demand for grain transportation for all modes may rise proportionately.

- In August, USDA projected 2007/08 corn exports at 2.15 billion bushels (up 50 million bushels from last year). Projected corn exports, however, decline in 2008/09 and 2009/10 before increasing in subsequent years, which leads to variability in overall rail and barge transportation demand, assuming the historical 5-year average modal share stays the same.

- Price competition in different locations (corn basis) may shift transportation patterns more frequently than in the past because corn used for fuel has created an additional demand for corn and corn origination patterns may change as ethanol production increases. However, if corn supplies are abundant, there may be less price competition and thus fewer shifts in transportation patterns.

Transportation requirements could increase as ethanol production reaches 15 billion gallons by 2016; demand for rail and barge services then may recede as export demand decreases under the 20 billion gallon scenario (graphs, click to enlarge). In the near-term, however, sharp increases in ethanol and DDGS movements are expected to offset any decreases in rail and barge grain transportation due to decreased exports and domestic use.

Transportation requirements could increase as ethanol production reaches 15 billion gallons by 2016; demand for rail and barge services then may recede as export demand decreases under the 20 billion gallon scenario (graphs, click to enlarge). In the near-term, however, sharp increases in ethanol and DDGS movements are expected to offset any decreases in rail and barge grain transportation due to decreased exports and domestic use.Trucking demand continues to grow for all three scenarios, increasing most dramatically as ethanol production grows from the baseline to the 15-billion gallon target.

Increased ethanol production could lead major corn-producing states to become corn deficit states, resulting in the need to source corn from other states and increasing transportation distances for sourced feedstock. Corn prices are expected to vary by location to ration the demand between domestic feedlots, ethanol plants, and exports. For example, as demand for corn at ethanol plants increases, corn prices may strengthen near the ethanol-producing areas relative to corn prices in export locations.

This impact is demonstrated by the corn basis, which is the difference between the local cash prices and the nearby Chicago Board of Trade futures contract. Transportation demand may be higher in the areas with stronger prices (stronger basis). Increases in transportation costs, however, may also weaken (decrease) the interior basis, which would cause farm prices to fall in those locations.

The domestic corn basis during the first half of 2007 has been strengthening relative to exports until recently. Corn futures prices have been decreasing from the high of over $4.00 in the spring to $3.20 by the end of July. However, the corn basis in Nebraska and at the Gulf ports have been strong, indicating relatively stronger demand in those locations for ethanol and export use.

Rail

Railroads shipped about 60 percent of ethanol produced in the United States in 2005, or 82,483 carloads and have kept up with the annual ethanol production growth of 26 percent in 2006. According to preliminary Freight Commodity Statistics, the Class I railroads’ origination of all alcohols grew by 28 percent.

The expected growth in rail movements of ethanol may pose some hurdles for shippers. Ethanol volumes moved by rail could jump from the projected 190,816 carloads in 2007 to over 408,000 in 2016 (table, click to enlarge). Class I railroads, however, assert that the additional volume due to ethanol is well below the 20.8 million carloads of cargo freight they originated in 2006.

The expected growth in rail movements of ethanol may pose some hurdles for shippers. Ethanol volumes moved by rail could jump from the projected 190,816 carloads in 2007 to over 408,000 in 2016 (table, click to enlarge). Class I railroads, however, assert that the additional volume due to ethanol is well below the 20.8 million carloads of cargo freight they originated in 2006.The variability and uncertainty of rail grain transportation demand is a function of grain export projections. For example, in the 20-bgy scenario, projected grain exports decline and rail grain transportation demand would decrease. However, that decrease is more than offset by the increased demand for ethanol and DDGS rail transportation. The consequences of the increased ethanol and DDGS transportation under the 20-bgy scenario occurring during a relatively short period could include a strain on rail transportation and logistics infrastructure.

Thus, the interdependence of corn used for fuel vs. corn used for feed (domestic and exports) may translate into uncertainty for rail transportation.

Unit Train Economics

It is more efficient and cost effective for railroads to move unit trains. The primary reasons include a higher asset utilization rate and lower inventory carrying costs. The industry “rule of thumb” is that the ethanol railcar utilization rate for a unit train is 30 turns per year, compared to 12 turns per year for a single-car shipment. Inventory carrying costs (travel, dwell, and unloading times) for a single-car shipment of ethanol could be as much as four-times that of a unit train.

Unit train movements would increase the average number of loadings per year for each ethanol tank car, which could help alleviate potential tank car shortages.

Rail tariff rates for unit trains are typically lower than those for single-car and smaller shipments. For example, BNSF’s tariff rate is discounted $900 for a gathered unit train of ethanol vs. a single car shipment of ethanol from Southwest Iowa to the Los Angeles Basin, California.

Construction of unit train infrastructure at destination terminals—mostly owned by blenders, refiners, and third-party providers—may become a key to the efficiency of rail ethanol transportation. Factors that may be contributing to a slower rate of the infrastructure development include its capital-intensive nature as well as the sometimes-lengthy permitting process.

Similar economics are developing in the DDGS rail shipments. Unit trains of DDGS are currently discounted on BNSF by approximately $7.50 per ton relative to single car movements.11 Additional DDGS storage at origin and unit train unloading infrastructure at destination would encourage further unit train utilization of DDGS.

Infrastructure issues

Supply Chain Issues

Several supply chain issues could inhibit growth in the ethanol industry. The efficiency of the ethanol transportation system may begin to depend on the ability of the blending market to accommodate additional quantities of ethanol.

The supply and demand of ethanol may become temporarily out of balance because blenders require time and financial incentives to add blending capacity. These extra financial incentives, including cheaper ethanol, could be in addition to the current blender tax credit of $0.51 per gallon, which is in place through 2010. Blenders are watching Federal and State legislative processes carefully to assess the legislative risk to their capital investments. Grain markets may also be affected by ethanol supply chain issues. There is concern that grain storage shortages may occur as ethanol production capacity and corn crops continue to expand.

Rail Capacity

Rail capacity typically depends on several factors, including locomotive power and railcar availability and utilization, which are affected by train speeds, dwell time, loading and unloading times, and track capacity. In addition to an efficient logistics infrastructure, an adequate supply of railcars and other transportation equipment for ethanol and DDGS are needed to sustain growth in the ethanol industry.

Ethanol Rail Tank Cars

Ethanol is shipped in standard rail tank cars (approved for flammable liquids)—DOT 111A or AAR T108 rail cars. As of January 1, 2007, 41,000 rail tank cars capable of shipping ethanol were in use. Orders for new cars increased substantially in 2006 with a surge in ethanol plant construction and are expected to almost double this fleet in the next 2–2½ years. Rail tank cars are nearly all privately owned, either by leasing companies or shippers. Orders for new rail tank cars, 75 percent of which are estimated to be for ethanol use, started to increase in the 4th quarter 2005 and continued to increase through the 3rd quarter 2006 (Figure 9). Rail tank car manufacturers increased production lines, but the backlog grew from about 10,000 railcars in the 3rd quarter 2005 to a peak of 36,334 railcars in the 4th quarter 2006. By the end of 1st quarter 2007, the manufacturing backlog had decreased to 36,166 railcars.

Grain Rail Cars

Increased rail service demand is expected to affect railcar fleet composition and availability for moving corn, ethanol, and DDGS. Most grain is shipped in designated covered hopper railcars C113, C114, C213, or C313, which can also be used for other dry bulk commodities. Total covered hopper railcar fleet as of January 1, 2007, was 268,000 railcars—almost 2 percent higher than on January 1, 2005. However, the grain rail car fleet share is estimated to be approximately 160,800—60 percent of the total covered hopper fleet.

Distillers Dried Grains with Solubles (DDGS) Transportation Issues Ethanol plants that use corn as feedstock produce a co-product called distillers grains (DDGSdried distillers grains with solubles, WDG-wet distillers grains, and MDG-modified distillers grains). For every 56-pound bushel of corn, 17.5 pounds of DDGS and 2.76 gallons of ethanol are produced, on average. Dairy cattle operations and cattle feedlots are the primary domestic users of distilled grains as a protein supplement for the ruminant animals.

Research is ongoing for increasing the DDGS use by poultry and hog operations, which currently is limited due to nutritional challenges DDGS present to non-ruminant animals.

Production of DDGS is expected to grow proportionately with ethanol production increases. Currently, about 10 percent of DDGS are exported—1.25 million metric tons (mt) in 2006.

According to the USDA’s Foreign Agricultural Service (FAS), the United States exported approximately 900,000 metric tons of DDGS during the first 6 months of 2007—60 percent higher than the same period last year. The trend of increased DDGS exports is expected to continue. Increased use of barges to ship DDGS to export locations is likely.

The original co-product of distilled grains from ethanol production is wet distillers grains (WDG). Shipping the WDG’s saves energy, but the product is perishable and needs to be trucked to a nearby feeding operation within a couple of days. Drying the product adds cost for the ethanol producer, but provides a more stable product for transport and storage. Railroads and barges ship DDGS long distances and trucks are used for shorter distances.

Demand for shipping DDGS to domestic and export markets has been increasing, thus expanding demand for super jumbo covered hoppers—railcars that are greater than 5,500 cubic feet (ft3) and have wide gates for easier flowability. During storage and transport, DDGS tends to cake and bridge between particles. Thus, flowability has become one of the major issues that needs to be addressed for effective sales, marketing, distribution, and utilization of distillers grains. Because these co-products do not always flow easily from railcars, workers sometimes hammer the car sides and hopper bottoms in order to induce flow. This can lead to severe damage to the rail cars themselves and can also pose worker safety issues.

According to the Rail Supply Institute, from first quarter 2005 through first quarter 2007, new deliveries of super jumbo railcars have totaled 11,307, with most of the growth occurring in 2006. DDGS are estimated to use about 70 percent of this fleet. DDGS railcars are nearly all privately owned.

Flowability issues associated with shipping DDGS, based on the feed industr experience of using regular grain covered hoppers, have created expectations of a shorter lifespan for railcars used to ship DDGS. DDGS are also shipped in containers for export. The same flowability issues have started to affect availability of containers. DDGS transportation may be affected if feedlot operations move closer to the ethanol producing areas—more distillers’ grains would be sold wet, requiring less rail and more truck transportation to feedlots and decreasing availability of DDGS for export.

Truck Service

Corn for ethanol is most frequently delivered to plants by trucks, typically from corn farms within a 50-mile radius. The truckload requirements just for corn to ethanol—if trucks are assumed to carry 98 percent of the corn delivered to ethanol plants—are expected to increase from 2.3 million in 2006 to 4.7 million truckload equivalents by 2016. The demand for corn trucking increases substantially—to 5.9 and 7.8 million truckloads under scenarios 1 and 2, respectively (table, click to enlarge).

Corn for ethanol is most frequently delivered to plants by trucks, typically from corn farms within a 50-mile radius. The truckload requirements just for corn to ethanol—if trucks are assumed to carry 98 percent of the corn delivered to ethanol plants—are expected to increase from 2.3 million in 2006 to 4.7 million truckload equivalents by 2016. The demand for corn trucking increases substantially—to 5.9 and 7.8 million truckloads under scenarios 1 and 2, respectively (table, click to enlarge).Standard gasoline tanker trucks (DOT MC306 Bulk Fuel Haulers) are used to ship ethanol from ethanol plants to the blending terminals. These trucks move an estimated 30 percent of ethanol. The current fleet size of the independently operated tank trucks is approximately 10,000. Many petroleum companies own their tanker truck fleet and are not included in the total.

Constraints to truck service include the availability of truck drivers (especially with HAZMAT certification), equipment shortages, and the differences in ethanol routes from the well-established and predictable petroleum routes—in part due to the rapid growth of new ethanol plant construction. In addition, overall truck freight is forecast to almost double from 2002 to 2020, while driver shortages are projected to reach 219,000 by 2015. In 2004, there were 1.3 million long-haul heavy-duty truck drivers.

Tank Barge Service

Barges move an estimated 10 percent of ethanol. The main terminals served by barge include Chicago, IL, New Orleans, LA, Houston, TX, and Albany, NY. Ethanol is typically shipped in 10,000–15,000 barrel tank barges. The number of ethanol plants located near a river facility, however, is relatively small. As the industry grows, the share moved by barge may increase. According to Informa Economics, 2,808 tank barges were in operation in 2006, up from 2,782 in 2005, and 2,777 in 2004.

Construction of a 16.6-million-gallon ethanol terminal on the Mississippi River at Sauget, IL, is expected to be completed by June 2008. The Army Corps of Engineers has approved construction of a 5th ethanol storage tank at this location to hold an additional 480,000 gallons by the third quarter of 2008. The terminal will be capable of loading 1.26-million-gallon tank barges as well as 95-car unit trains and trucks.

Potential Pipeline Developments

Pipelines are considered to be the safest and most cost-efficient mode of transportation. The ethanol industry, however, is fairly dispersed and significant infrastructure investments would still be necessary to consolidate sufficient quantities that could then be moved through pipelines.

No ethanol is currently shipped by pipeline due to its corrosive nature and ability to attract water. The pipeline industry, however, led by the Association of Oil Pipe Lines (AOPL) and American Petroleum Institute (API), is moving forward with an accelerated research program to address integrity issues related to shipping ethanol/gasoline blends (earlier post).

The project, managed by the Pipeline Research Council International (PRCI), will focus on an accelerated research effort due to be concluded in 6-12 months. It plans to identify those blends that:

- Can be moved in existing pipelines with little to no modification to the system.

- Can be moved with appreciable modifications.

- Cannot be moved in existing systems but could be moved in specially designed new transmission or short-haul distribution systems

References:

USDA AMD: USDA releases report on implications of ethanol production on agricultural transportation - September 21, 2007.

USDA ADM: Expansion of U.S. Ethanol from the Agricultural Transportation Perspective [*.pdf] - Transportation and Marketing Programs Transportation Services Branch

- September 2007

Biopact: U.S. House passes Energy Bill: boost to biofuels, CCS and renewables - August 06, 2007

--------------

--------------

Spanish engineering and energy company Abengoa says it had suspended bioethanol production at the biggest of its three Spanish plants because it was unprofitable. It cited high grain prices and uncertainty about the national market for ethanol. Earlier this year, the plant, located in Salamanca, ceased production for similar reasons. To Biopact this is yet another indication that biofuel production in the EU/US does not make sense and must be relocated to the Global South, where the biofuel can be produced competitively and sustainably, without relying on food crops.

Spanish engineering and energy company Abengoa says it had suspended bioethanol production at the biggest of its three Spanish plants because it was unprofitable. It cited high grain prices and uncertainty about the national market for ethanol. Earlier this year, the plant, located in Salamanca, ceased production for similar reasons. To Biopact this is yet another indication that biofuel production in the EU/US does not make sense and must be relocated to the Global South, where the biofuel can be produced competitively and sustainably, without relying on food crops.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Links to this post:

Create a Link

<< Home