UNCTAD: poorest countries need investments in science and technology

The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) today released its annual Least Developed Countries Report 2007 [*.pdf], in which it calls for a boost in investments in science, technology and innovation (STI) in the poorest countries. After years of focusing attention on market reform and economic liberalization (1990s) and then on 'good governance' (2000s), the least developed countries (LDCs) now need more knowledge-based development if they want to escape the poverty trap. LDCs are defined as the 50 poorest countries - the majority of them in Africa - whose combined population totals 767 million.

Over the past 25 years, STI projects and knowledge-based development initiatives have received marginal funds from the major international development agencies (e.g. in 2003–2005 'good governance' received $1.3 billion, agricultural extension a meagre $12 million...). Now, the UNCTAD sees investments in technology, science and learning environments as crucial for poverty reduction strategies.

The overal argument of the UNCTAD's analysis is that:

The subject of knowledge, technological learning and innovation is a large one, and the important UNCTAD report is the first to address the issue in the context of the least developed countries. It focuses on five issues:

So what kind of strategies does the UNCTAD recommend, in order to boost STI and knowledge-based development? First of all, it is important to look at how technological change happens in LDCs, because the process differs considerably from that in highly developed countries:

sustainability :: bioeconomy :: development :: science :: technology :: innovation :: good governance :: development aid :: poverty alleviation :: Africa :: UNCTAD ::

sustainability :: bioeconomy :: development :: science :: technology :: innovation :: good governance :: development aid :: poverty alleviation :: Africa :: UNCTAD ::

Processes of technological change in rich countries, where firms are innovating by pushing the knowledge frontier further, are fundamentally different from such processes in developing countries. There, innovation primarily takes place through enterprises learning to master, adapt and improve technologies that already exist in more technologically advanced countries:

The development of firm-level capabilities and support systems is vital for successful assimilation of foreign technology. There's a difference between 'core competences', 'dynamic capabilities', and 'technological capabilities':

Core competences

Core competences refer to the knowledge, skills and information to operate established facilities or use existing agricultural land, including production management, quality control, repair and maintenance of physical capital, and marketing.

Dynamic capabilities

Dynamic capabilities refer to the ability to build and reconfigure competences to increase productivity, competitiveness and profitability and to address a changing external environment in terms of supply and demand conditions.

Technological capabilities

Technological capabilities as such are particularly important for the process of innovation. The effective absorption (or assimilation) of foreign technologies depends on the development of such dynamic technological capabilities. R&D can be part of those capabilities, but only a part. Design and engineering capabilities are particularly important for establishing new facilities and upgrading them.

Beyond this, production processes involve various complex organizational processes related to the organization of work, management, control and coordination, and the valorization of output requires logistic and marketing skills. All these can be understood as part of “technological learning” in a broad sense.

Context: policy, institutional framework

The enterprise (firm or farm) is the locus of innovation and technological learning. But firms and farms are embedded within a broader set of institutions which play a major role in these processes. In advanced countries, national innovation systems have been established to promote R&D and link it more effectively to processes of innovation. In LDCs, what matters in particular are the domestic knowledge systems which enable (or constrain) the creation, accumulation, use and sharing of knowledge.

Those systems should support effective acquisition, diffusion and improvement of foreign technologies. In short, there is a need to increase the absorptive capacity (or assimilation capacity) of domestic firms and the domestic knowledge systems in which they are embedded.

1. Building technological capacilities through international market linkages

The level of development of technological capabilities in LDCs is very weak, the report notes. Indicators to show this are scarce and not wholly appropriate. But an examination of where LDCs stand on some of the key indices reveals a dismal performance from an international comparative perspective.

The domestic knowledge systems in the LDCs are very weak and the level of technological capabilities of domestic enterprises is very low. Initiating a sustainable process of knowledge accumulation that could accelerate the development of productive capacities in the LDCs will not be a simple task, because classic recipes have failed:

So how can poor countries tap these international knowledge and technology pools?

The report looks at different options, including (1) imports of capital goods, (2) learning by exporting, (3) foreign direct investment, and (4) licensing.

Imports of capital goods

By far the most important source of technological innovation in LDCs, as perceived by firms themselves, is new machinery or equipment. Most of the machinery and equipment operated in LDCs is imported, and therefore imports of capital goods, and their effective use, are overall the main source of innovation for firms in LDCs.

But capital good imports by LDCs have lost momentum over the last 25 years. They have been hampered by their premature de-industrialization process, the slow progression of the investment rate, the composition of their fixed capital formation (with a low share of machinery and equipment) and balance-of-payments restrictions. The sluggishness of those imports means that domestic firms are upgrading their processes and products only marginally. Importing relatively few capital goods implies that LDC firms are forgoing the potential technological learning and adaptive innovation associated with a greater volume of imports of technology embodied in those goods.

Different countries often limit their imports of capital goods to develop the most obvious sectors (a country with mining potential imports mining machines, oil rich countries import oil processing tools, etc...). But, interestingly, when it comes to agriculture and ICT - crucial for all countries, regardless of their other natural resources - the report notes:

Exports and the role of global value chains

The report suggests that LDC firms can develop their technological capabilities through the market linkages they develop with their downstream customers, including in particular the foreign ones. Integration into global value chains (GVCs) often represents one of the very few options for LDC firms and suppliers to secure access to international markets and innovative technologies, and to learn by exporting.

However, the upgrading process is fraught with difficulties and obstacles, which are particularly great for LDC firms. International value chains are increasingly driven by buyers and downstream lead firms. The latter have the power to set the standards (technical, quality, environmental) that must be met in order to participate in the chain. Chain leaders, however, rarely help producers to upgrade their technological capabilities so that they are able to fulfil those requirements. Barriers to integrate such global value chains are therefore becoming higher.

Foreign direct investment

It is generally contended that the arrival of transnational corporations leads to technological upgrading of domestic firms through technological spillovers via imitation, competition, training, labour mobility, backward and forward linkages, and exports (which entail exposure to the technology frontier). Those spillover effects have the potential to increase the productivity of other firms.

However, the materialization of the potential positive impacts of FDI on knowledge accumulation in host countries hinges on a large number of conditions, including their structural characteristics, the type of insertion of transnational corporations in host economies, their job-generating impact, and the direct consequence of their entry for domestic firms.

The report notes that foreign direct investments in the LDCs have sped up markedly over the past few years, but as such this is not sufficient to guarantee technology spill-overs to local firms:

Licensing

The use of licensing as a channel for accessing the international knowledge pool (through imports of disembodied technology) is directly related to the income level and technological sophistication of economies. Licensing should therefore be less relevant to LDCs than to other developing countries as a channel for foreign technology diffusion

In conclusion, the report notes that learning associated with international transactions does not occur automatically. Consequently, measures to increase the volume of exports or FDI inflows do not guarantee any increase in learning.

2. National policies to promote technological learning and innovation

The report notes that in current development and poverty alleviation discourses, the need for improved technology and science policies receives little attention.

Partly to blame are the so-called 'structural adjustment programmes', which have been particularly intensely implemented within the LDCs. These programmes, pushed by the World Bank and the IMF and mainly aimed at economic liberalisation, show great omissions of technology issues.

However, the UNCTAD notes that this presents a paradox, because these very institutions have always stressed that promoting technological change is as a key source of economic growth: technological progress is at the heart of efforts by the OECD to promote growth in its own member countries.

Policy suggestions

The UNCTAD gives some suggestions as to how LDCs can embed attention for science and technology into their national development strategies. Laying the foundations of such an integrated policy would consist of the following steps.

These are the foundations. But the report goes further and has identified six major strategic priorities for LDCs at the start and the early stages of catch-up:

Such a systematic approach should include:

The relevant STI policy tools thus include explicit measures which are concerned with S&T human resource development, public S&T infrastructure and policies to affect technology imports.

But beyond this they include a number of implicit measures, such as public physical infrastructure investment; financial and fiscal policies which increase the incentive for investment and innovation; trade policy and competition policy; public enterprises and public procurement; and regulation, notably in relation to intellectual property rights and other innovation incentive mechanisms.

Most importantly:

Role of the State

Within such a new industrial policy, the State should act as a facilitator of learning and entrepreneurial experimentation. The private sector is the main agent of change. However, the relevant institutions and cost structures are not given but need to be discovered. The State should facilitate this process and play a catalytic role in stimulating market forces; and it should perform a coordinating function based on an agreed strategic vision of country-level priorities for technological development.

There are significant private sector risks in undertaking pioneer investments which involve setting up activities that are new to a country. Moreover, there are significant spillover effects which are beneficial to the country but which the private entrepreneur cannot capture. This implies the need for a partnership and synergies with the public sector to socialize risks and promote positive externalities. The State stimulates and coordinates private investment through market-based incentives aimed at reducing risks and sharing benefits.

STI governance

The major trend of the past few years in development thinking stressed 'good governance' and ways to strengthen State capacities. And indeed, it could be argued that the suggested STI policies will never work in LDCs because State capacities there are simply too weak.

UNCTAD notes however that policies and projects introduced during the 'good governance' years, were just as complex as those aimed at promoting STI:

3. Intellectual property rights

The UNCTAD report contains an interesting chapter on how intellectual property rights (IPRs) can contribute to technology learning. But for this lever to bear fruit, players have to go through several complex stages. For the time being, IPRs won't play that much of a role in the least developed countries:

For biofuels and bioenergy to benefit local communities and LDC economies, it is crucial that local expertise is used, or that it is created. If scientists, engineers and management are recruited from abroad, chances are that knowledge and technology capabilities will not spill-over to local actors. On the other hand, a brain drain of biotechnologists, agronomists and engineers from LDCs to developed countries, jeapordizes the establishment of science and technology-based bioeconomies.

The UNCTAD report sees the importance of these movements of 'brain drain' and 'brain gain', and their impacts on the knowledge stock of LDCs.

International migration of skilled persons in principle contributes to building the recipient countries’ skills endowment, while entailing a loss in the origin country’s stock of human capital. The most important issue for countries’ long-term development is the net effect of migratory flows. LDCs have a low skill endowment. Therefore, the international migration of skilled persons from and to those countries can have a strong impact on their human capital stock.

But the UNCTAD warns that these positive effects of 'brain circulation' are not likely to occur in LDCs, for clear reasons:

For the LCDs, three main features of skilled emigration have been observed since the 1990s:

The UNCTAD formulates policy recommendations on how best to deal with these migration flows, in such a way that they limit the impact on the knowledge-base of the LDCs.

5. 'Knowledge aid'

The classic saying goes that it's better to teach a man how to fish, than to throw him a fish whenever he's hungry. Likewise, the justification for foreign aid is often articulated only on the basis of pressing economic, social and political objectives (e.g. food aid, with less attention for teaching people how to grow more food).

So more fundamentally, aid can help to build up the knowledge resources and knowledge systems of LDCs. This is particularly important for the LDCs because their level of technological development is so low and technological learning through international market linkages is currently weak.

Knowledge aid can be provided in two ways:

Aid to build STI capacities

Aid to build science, technology and innovation capacity is a particular form of knowledge aid and should support:

A brief overview of the numbers for 2003-2005 for all LDCs combined show that knowledge aid has captured a marginal share of the overall aid budgets:

emphasized in the routine poverty alleviation programmes, namely agricultural research and extension, aid commitments to LDCs have actually fallen rather than risen since the late 1990s. Compare this with the annual technical cooperation commitments to improve 'governance' (in the widest sense). In 2003–2005 these were $1.3 billion. Agricultural extension received $12 million...

As the UNCTAD report simply notes: it will be impossible to ensure 'good governance' if States don't have a productive and viable economy to build on and to draw incomes from.

The authors make some policy recommendations that could help deal with the problem of the lack of aid going to knowledge, technology and science. The recommendations are offered per sector:

Agricultural R&D

Although agriculture is the major livelihood in the LDCs, the current agricultural research intensity – expenditure on agricultural research as a share of agricultural GDP – is only 0.47 per cent. That compares with 1.7 per cent in other developing countries. The LDC agricultural research intensity is far below the 1.5 to 2 per cent recommended by some international agencies. Moreover, the low level reflects a serious decline in the agricultural research intensity in the LDCs since the late 1980s, when the figure stood at 1.2 per cent.

Non-agricultural technological learning and innovation

Agriculture is still the major source of employment and livelihood in the LDCs, but the employment transition which they are undergoing means that this position is not tenable if development partners wish to reduce poverty sustainably and substantially.

One important recommendation for the non-agricultural sector is that donor-supported physical infrastructure projects should all include components use the construction process to develop domestic design and engineering capabilities.

In addition, there is a need for public support for enterprise-based technological learning, which should be in the form of grants or soft loans for investment in the relevant types of knowledge assets. Such support should be undertaken as a costsharing public–private partnership for creating public goods, particularly in relation to the development of design and engineering skill through enterprise-based practice. These STI capacity-building activities could be particularly useful if they are linked to value chain development schemes, FDI linkage development and the facilitation of South–South cooperation.

“Aid for Trade”

There is widespread support for scaling up this kind of aid amongst LDCs. Experiences show that technological learning and innovation are central to successful cases of trade development. However, technological learning and innovation have been conspicuously absent from past efforts to provide Aid for Trade. They are neglected within current attempts to define the scope of the subject.

It is recommended that aid for technological learning and innovation for tradable sectors be a key component of Aid for Trade, and LDC development partners should adopt best practices which are evident from successful cases of trade development, such as palm oil in Malaysia and Nile perch in Uganda. Note that environmentalists have condemned precisely these two examples as cases of how trade development can destroy the most basic foundations of sustainability.

Conclusion

By way of conclusion, we can say that many insights and recommendations from the UNCTAD report can be readily applied to the development of strategies with which LDCs can approach the opportunities of the emerging bio-economy. Such an new, green economy holds the potential to boost local development and allows poor countries to leapfrog beyond the fossil fuel era. But in order to transit towards this sustainable, biobased economy, investments in knowledge and technology are urgently needed. The sector is highly competitive, and mere comparative advantages (agro-ecological resources) won't suffice for these countries to participate in it in a meaningful way.

Biopact readers know that we have often stressed the need for appropriate tech transfer strategies in the biofuels sector. Brazil has gone some way in this respect, and has forged South-South collaboration efforts by linking its own expert agricultural research organisations with those of poor countries. There's also France's bioenergy knowledge-exchange initiative, which couples students from the country to collegues in developing countries. But overall, these initiatives remain marginal. A much more urgent and broader effort is needed to create robust ways for the North to help the South strengthen its capacities to boost investments in STI.

For example, policies in LDCs must ensure that when foreign companies from highly developed countries enter the sector in poor countries, technology and knowledge transfers as well as opportunities for joint-ventures occur that allow local players to acquire expertise and technological capabilities. Else, biofuels may become just another 'resource grab'.

On the other hand, States need to craft policies and infrastructures that make it possible for local players to 'absorb' knowledge (it's a two-way process). Finally, as we have stressed earlier, national and international policy frameworks and investments in STI in developing countries are crucial for the bioenergy sector to flourish in a genuinely sustainable way.

Professor John Mathews, an expert on STI and knowledge-driven industrial development strategies has writen in-depth analyses on the subject as it relates to the biofuels sector in developing countries (for an example, see 'A Biofuels Manifesto').

On an ending note, consider this. Those of us who understand the complex and multi-dimensional concept of 'sustainable development' will admit that such an understanding requires study, exchanges between thinkers, scientists and policy makers. Don't we all want the people in the South - who are often merely the passive subjects of such concepts - to acquire the capacities needed to develop their own notions of sustainability and the skills to implement them?

References:

UNCTAD: The Least Developed Countries Report, 2007. Knowledge, technical learning and innovation for development [*.pdf, full report] - July 2007.

UNCTAD: The Least Developed Countries Report, 2007 [*.pdf, summary] - July 19, 2007.

UNCTAD: The Least Developed Countries Report, 2007, Highlights - July 19, 2007.

John Mathews, A Biofuels Manifesto: Why Biofuels Industry Creation Should be 'Priority Number One' for the World Bank and for Developing Countries [*.pdf] - September 2006.

Over the past 25 years, STI projects and knowledge-based development initiatives have received marginal funds from the major international development agencies (e.g. in 2003–2005 'good governance' received $1.3 billion, agricultural extension a meagre $12 million...). Now, the UNCTAD sees investments in technology, science and learning environments as crucial for poverty reduction strategies.

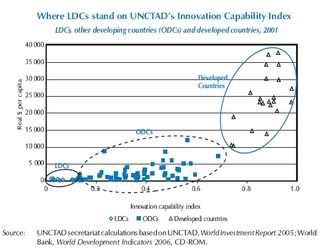

Comparison of the capability of countries to innovate: a huge gap between highly developed and least developed countries (click to enlarge).

The overal argument of the UNCTAD's analysis is that:

unless the LDCs adopt policies to stimulate technological catch-up with the rest of the world, they will continue to fall behind other countries technologically and face deepening marginalization in the global economy. Moreover, the focus of those policies should be on proactive technological learning by domestic enterprises rather than on conventionally understood technological transfer, and on commercial innovation rather than on pure scientific research.The report also stresses that sheer economic liberalization - long the mantra of development agencies - is no guarantee for successful development, on the contrary:

Since the 1990s most LDCs have undertaken rapid and deep trade and investment liberalization. Liberalization without technological learning will result, in the end, in increased marginalization.The report contains many interesting observations that can directly be linked to the biofuels and bioenergy industry that is emerging in LDCs. Such an industry holds the potential to boost local development, but a precondition is that the sector becomes knowledge and technology-driven instead of merely relying on static comparative advantages of LDCs.

The subject of knowledge, technological learning and innovation is a large one, and the important UNCTAD report is the first to address the issue in the context of the least developed countries. It focuses on five issues:

- the extent to which the development of technological capabilities is occurring in LDCs through international market linkages, particularly through international trade, foreign direct investments and licensing

- the way in which STI issues are currently treated within LDCs and how STI policies geared towards technological catch-up could be integrated into the development strategies of LDCs

- current controversies about how stringent intellectual property rights regimes affect technological development processes in LDCs and policy options for improving their learning environment

- the extent of loss of skilled human resources through emigration and policy options for dealing with that issue

- how overseas development aid is supporting technological learning and innovation in the LDCs and ways to improve it

So what kind of strategies does the UNCTAD recommend, in order to boost STI and knowledge-based development? First of all, it is important to look at how technological change happens in LDCs, because the process differs considerably from that in highly developed countries:

sustainability :: bioeconomy :: development :: science :: technology :: innovation :: good governance :: development aid :: poverty alleviation :: Africa :: UNCTAD ::

sustainability :: bioeconomy :: development :: science :: technology :: innovation :: good governance :: development aid :: poverty alleviation :: Africa :: UNCTAD :: Processes of technological change in rich countries, where firms are innovating by pushing the knowledge frontier further, are fundamentally different from such processes in developing countries. There, innovation primarily takes place through enterprises learning to master, adapt and improve technologies that already exist in more technologically advanced countries:

The central issue is not acquisition of the capability to invent products and processes. Rather, policies to promote technological change in LDCs, as in all developing countries, should be geared to achieving catch-up with more technologically advanced countries. That is, they are concerned with learning about and learning to master ways of doing things that are used in more technologically advanced countries.It can hardly be expected that an LDC is already knocking at the frontiers of technological breakthroughs. Creative technological innovation also occurs when products and processes that are new to a country or an individual enterprise are commercially introduced, whether or not they are new to the world, the report says.

In short, innovation occurs through "creative imitation", as well as in the more conventional sense of the commercialization of inventions.Different economic sectors are based on unique processes of technology adoption. For agriculture, the type of technological effort that is required is influenced by agriculture's high degree of sensitivity to the physical environment (circumstantial sensitivity). The strong interaction between the environment and biological material makes the productivity of agricultural techniques, which are largely embodied in reproducible material inputs, highly dependent on local soil, climatic and ecological characteristics. This means that there are considerable limits to the agricultural development which can occur simply through the importation of seeds, plants, animals and machinery (agricultural technology) that are new to the country.

What is required is experimental agricultural research stations to conduct tests and, beyond that, indigenous research and development capacity to undertake the inventive adaptation of prototype technology which exists abroad – for example, local breeding of plant and animal varieties to meet local ecological conditions. Without such inventive adaptation capabilities, knowledge and techniques from elsewhere are locally of limited use.For industry and services, such circumstantial sensitivity is less important, but nevertheless technological effort is required because technology is not simply technological means (such as machinery and equipment) and technological information (such as instructions and blueprints), but also technological understanding (know-how). The latter is tacit and depends on learning through training, experience and watching.

The development of firm-level capabilities and support systems is vital for successful assimilation of foreign technology. There's a difference between 'core competences', 'dynamic capabilities', and 'technological capabilities':

Core competences

Core competences refer to the knowledge, skills and information to operate established facilities or use existing agricultural land, including production management, quality control, repair and maintenance of physical capital, and marketing.

Dynamic capabilities

Dynamic capabilities refer to the ability to build and reconfigure competences to increase productivity, competitiveness and profitability and to address a changing external environment in terms of supply and demand conditions.

Technological capabilities

Technological capabilities as such are particularly important for the process of innovation. The effective absorption (or assimilation) of foreign technologies depends on the development of such dynamic technological capabilities. R&D can be part of those capabilities, but only a part. Design and engineering capabilities are particularly important for establishing new facilities and upgrading them.

Beyond this, production processes involve various complex organizational processes related to the organization of work, management, control and coordination, and the valorization of output requires logistic and marketing skills. All these can be understood as part of “technological learning” in a broad sense.

Context: policy, institutional framework

The enterprise (firm or farm) is the locus of innovation and technological learning. But firms and farms are embedded within a broader set of institutions which play a major role in these processes. In advanced countries, national innovation systems have been established to promote R&D and link it more effectively to processes of innovation. In LDCs, what matters in particular are the domestic knowledge systems which enable (or constrain) the creation, accumulation, use and sharing of knowledge.

Those systems should support effective acquisition, diffusion and improvement of foreign technologies. In short, there is a need to increase the absorptive capacity (or assimilation capacity) of domestic firms and the domestic knowledge systems in which they are embedded.

1. Building technological capacilities through international market linkages

The level of development of technological capabilities in LDCs is very weak, the report notes. Indicators to show this are scarce and not wholly appropriate. But an examination of where LDCs stand on some of the key indices reveals a dismal performance from an international comparative perspective.

The domestic knowledge systems in the LDCs are very weak and the level of technological capabilities of domestic enterprises is very low. Initiating a sustainable process of knowledge accumulation that could accelerate the development of productive capacities in the LDCs will not be a simple task, because classic recipes have failed:

Technological assimilation and absorption in LDCs through market mechanisms are taking place only to a very limited degree, as reflected in the weak development of technological capabilities and productive capacities. For some channels, notably capital goods imports, the scale of interaction in relation to GDP is much too low. For other channels, notably FDI and exports, the scale of interaction is actually high, but the learning effects of those channels are low. Thus, the growing integration of LDCs into international trade and investment flows since the 1980s has not prevented their marginalization from technology flows.But the task is not impossible either. According to the UNCTAD, a strategy for catch-up needs to focus on the following fields:

- building of an endogenous knowledge base, which takes into account informal knowledge systems as they develop in the informal economy (including such things as creative repair, reprocessing and recycling of artefacts, including in some cases complex technologies)

- traditional knowledge plays a crucial role in various sectors, including agriculture, health and creative industries.

- learning through international linkages. This latter option is seen as vital by the UNCTAD.

So how can poor countries tap these international knowledge and technology pools?

The report looks at different options, including (1) imports of capital goods, (2) learning by exporting, (3) foreign direct investment, and (4) licensing.

Imports of capital goods

By far the most important source of technological innovation in LDCs, as perceived by firms themselves, is new machinery or equipment. Most of the machinery and equipment operated in LDCs is imported, and therefore imports of capital goods, and their effective use, are overall the main source of innovation for firms in LDCs.

But capital good imports by LDCs have lost momentum over the last 25 years. They have been hampered by their premature de-industrialization process, the slow progression of the investment rate, the composition of their fixed capital formation (with a low share of machinery and equipment) and balance-of-payments restrictions. The sluggishness of those imports means that domestic firms are upgrading their processes and products only marginally. Importing relatively few capital goods implies that LDC firms are forgoing the potential technological learning and adaptive innovation associated with a greater volume of imports of technology embodied in those goods.

Different countries often limit their imports of capital goods to develop the most obvious sectors (a country with mining potential imports mining machines, oil rich countries import oil processing tools, etc...). But, interestingly, when it comes to agriculture and ICT - crucial for all countries, regardless of their other natural resources - the report notes:

As a group LDCs imported relatively little agricultural machinery and ICT capital goods. This indicates, on the one hand, the low level of technological development of those countries’ agriculture and, on the other hand, the still incipient penetration by the recent wave of ICT and ICT-based innovation.

Exports and the role of global value chains

The report suggests that LDC firms can develop their technological capabilities through the market linkages they develop with their downstream customers, including in particular the foreign ones. Integration into global value chains (GVCs) often represents one of the very few options for LDC firms and suppliers to secure access to international markets and innovative technologies, and to learn by exporting.

However, the upgrading process is fraught with difficulties and obstacles, which are particularly great for LDC firms. International value chains are increasingly driven by buyers and downstream lead firms. The latter have the power to set the standards (technical, quality, environmental) that must be met in order to participate in the chain. Chain leaders, however, rarely help producers to upgrade their technological capabilities so that they are able to fulfil those requirements. Barriers to integrate such global value chains are therefore becoming higher.

In most cases LDCs have increased their specialization in relatively basic products at a low stage of processing. Those export patterns indicate that little technological upgrading has taken place recently among LDC firms, irrespective of their participation in GVCs.

Foreign direct investment

It is generally contended that the arrival of transnational corporations leads to technological upgrading of domestic firms through technological spillovers via imitation, competition, training, labour mobility, backward and forward linkages, and exports (which entail exposure to the technology frontier). Those spillover effects have the potential to increase the productivity of other firms.

However, the materialization of the potential positive impacts of FDI on knowledge accumulation in host countries hinges on a large number of conditions, including their structural characteristics, the type of insertion of transnational corporations in host economies, their job-generating impact, and the direct consequence of their entry for domestic firms.

The report notes that foreign direct investments in the LDCs have sped up markedly over the past few years, but as such this is not sufficient to guarantee technology spill-overs to local firms:

There is little evidence of a significant contribution by FDI to technological capability accumulation in LDCs. This is not due to those countries’ insufficient 'opening' to foreign investors, given the policy changes that they have enacted since the 1980s and the substantial growth of FDI penetration since the 1990s. Rather, its limited contribution is due to the type of integration of transnational corporations into host countries’ economies, the sectoral composition of FDI, the priorities of policies enacted by LDCs and the low absorptive capacity of those countries.Biopact notes that the biofuels and bioenergy potential in many LCDs is large and that part of it may be tapped by foreign companies, which could boost tech transfers via spill-over effects. But in this context, the report issues an interesting warning about what is needed for this to succeed. The lesson, from which parallels to a future biofuels industry can be drawn, comes from the African mining sector:

In African LDCs typically the mineral extraction activities of TNCs are capital-intensive, have little impact on employment, are highly concentrated geographically, have high import content and result in exports of their output as unprocessed raw materials. Most of those operations are wholly owned by foreign investors (rather than joint ventures) and a large share of their foreign exchange earnings is retained abroad. Those operations tend to operate as enclaves since they are weakly integrated into domestic economies, as they have few forward and backward linkages in host economies.Currently, some of the main channels for potential knowledge circulation between TNCs and domestic firms are largely absent, namely linkages, joint ventures and labour turnover.

Licensing

The use of licensing as a channel for accessing the international knowledge pool (through imports of disembodied technology) is directly related to the income level and technological sophistication of economies. Licensing should therefore be less relevant to LDCs than to other developing countries as a channel for foreign technology diffusion

In conclusion, the report notes that learning associated with international transactions does not occur automatically. Consequently, measures to increase the volume of exports or FDI inflows do not guarantee any increase in learning.

Instead, the learning intensity of such transactions is variable, and the key policy issue is to raise that "learning intensity" – that is, to increase the magnitude of knowledge and skill acquired “per unit” of exports, imports or inward FDI. It is on the learning potential of international linkages that policy – at national, regional and international levels – should focus.

2. National policies to promote technological learning and innovation

The report notes that in current development and poverty alleviation discourses, the need for improved technology and science policies receives little attention.

Partly to blame are the so-called 'structural adjustment programmes', which have been particularly intensely implemented within the LDCs. These programmes, pushed by the World Bank and the IMF and mainly aimed at economic liberalisation, show great omissions of technology issues.

However, the UNCTAD notes that this presents a paradox, because these very institutions have always stressed that promoting technological change is as a key source of economic growth: technological progress is at the heart of efforts by the OECD to promote growth in its own member countries.

The broad revival of interest in policies to promote technological change, partly inspired by the East Asian success, is indicative of wide dissatisfaction with current policies. There is a desire to find a new, post-Washington Consensus policy model, as well as the intuition that it is in this area – promoting technological change – that it is possible to find more effective policies to promote growth and poverty reduction. If LDCs do not participate in this policy trend they will be increasingly marginalized in the global economy, where competition increasingly depends on knowledge rather than on natural-resource-based static comparative advantage.

Policy suggestions

The UNCTAD gives some suggestions as to how LDCs can embed attention for science and technology into their national development strategies. Laying the foundations of such an integrated policy would consist of the following steps.

- Technological catch-up in LDCs will require the co-evolution of improvement in physical infrastructure, human capital and financial systems, together with improved technological capabilities within enterprises and more effective knowledge systems supporting the supply of knowledge and linkages between creators and users of knowledge.

- It will also require a pro-growth macroeconomic framework which can ensure adequate resources for sustained technological learning and innovation, as well as a pro-investment climate which stimulates demand for investment.

- Improving physical infrastructure, human capital and financial systems is absolutely vital because many LDCs are right at the start of the catch-up process and have major deficiencies in each of those areas. Without an improvement in these foundations for development, it is difficult to see how technological change will occur.

These are the foundations. But the report goes further and has identified six major strategic priorities for LDCs at the start and the early stages of catch-up:

- Increasing agricultural productivity in basic staples, in particular by promoting a new Green Revolution

- Promoting the formation and growth of domestic business firms

- Increasing the absorptive capacity of domestic knowledge systems

- Leveraging more learning from international trade and FDI

- Fostering diversification through agricultural growth linkages and natural resource-based production clusters (the bioenergy sector can become such a web of diversification)

- Upgrading export activities

Such a systematic approach should include:

- measures to stimulate the supply side of technology development, but also measures to stimulate the demand for technology development

- measures to lubricate the links between supply and demand, and measures that address framework conditions

- these measures should influence all the interrelated factors that affect the ability and propensity of enterprises (both firms and farms) to innovate.

The relevant STI policy tools thus include explicit measures which are concerned with S&T human resource development, public S&T infrastructure and policies to affect technology imports.

But beyond this they include a number of implicit measures, such as public physical infrastructure investment; financial and fiscal policies which increase the incentive for investment and innovation; trade policy and competition policy; public enterprises and public procurement; and regulation, notably in relation to intellectual property rights and other innovation incentive mechanisms.

Most importantly:

There is above all a need for improved coherence between macro- and microeconomic objectives. Excessive pursuit of macroeconomic stabilization objectives can undermine the development of conditions necessary for productive investment and innovation. In the past the instruments of STI policy were articulated through an oldstyle industrial policy which involved protection and subsidies for selected sectors. Those instruments should now be articulated within the framework of a new industrial policy which is based on a mixed, market-based model, with private entrepreneurship and government working closely together in order to create strategic complementarities between public and private sector investment.

Role of the State

Within such a new industrial policy, the State should act as a facilitator of learning and entrepreneurial experimentation. The private sector is the main agent of change. However, the relevant institutions and cost structures are not given but need to be discovered. The State should facilitate this process and play a catalytic role in stimulating market forces; and it should perform a coordinating function based on an agreed strategic vision of country-level priorities for technological development.

There are significant private sector risks in undertaking pioneer investments which involve setting up activities that are new to a country. Moreover, there are significant spillover effects which are beneficial to the country but which the private entrepreneur cannot capture. This implies the need for a partnership and synergies with the public sector to socialize risks and promote positive externalities. The State stimulates and coordinates private investment through market-based incentives aimed at reducing risks and sharing benefits.

STI governance

The major trend of the past few years in development thinking stressed 'good governance' and ways to strengthen State capacities. And indeed, it could be argued that the suggested STI policies will never work in LDCs because State capacities there are simply too weak.

UNCTAD notes however that policies and projects introduced during the 'good governance' years, were just as complex as those aimed at promoting STI:

There are major deficiencies in governmental capacity in LDCs, particularly with regard to long-neglected STI issues. However, the problem of State capacity needs to be seen in dynamic rather than static terms. Just as firms learn over time by doing, Governments also learn by doing. The key to developing State capacity in relation to STI issues is therefore to develop such capacity through policy practice.According to the report, States need some room to experiment with these STI policies, in line with countries’ development objectives. For successful catch-up experiences it is important that the Government does not act as an omniscient central planner. Instead, success and good governance for creating technology learning environments will depend on:

- the State formulating and implementing policy through a network of institutions which link government to business.

- the establishment of intermediary government–business institutions

- policies should never favour or protect special interest groups, or support particular firms (“cronyism”)

- the State apparatus itself should undergo the necessary organizational restructuring because technological learning and innovation is naturally cross-sectoral. Merely establishing Science & Technology Ministries won't suffice and can even lead to an overemphasis on science and an underemphasis on innovation at the enterprise level. The appropriate organizational structure for integrating technological development issues into policy processes needs careful consideration.

3. Intellectual property rights

The UNCTAD report contains an interesting chapter on how intellectual property rights (IPRs) can contribute to technology learning. But for this lever to bear fruit, players have to go through several complex stages. For the time being, IPRs won't play that much of a role in the least developed countries:

IPRs are unlikely to play a significant role in promoting local learning and innovation in the initiation stage, the point in the catch-up process where most LDCs are now located. Moreover, technology transfer through licensing is unlikely to provide great benefits for LDCs. Even if under certain conditions IPRs were to positively encourage technology transfer through licensing, LDCs are unlikely to become significant recipients of licensed technology. The low technical capacity of local enterprises constrains their ability to license in technology, while the low GDP per capita in LDCs is not likely to stimulate potential transferors to engage in such arrangements. IPRs, particularly patents, promote innovation only where profitable markets exist and where firms possess the required capital, human resources and managerial capabilities.4. International migration of skilled labor

For biofuels and bioenergy to benefit local communities and LDC economies, it is crucial that local expertise is used, or that it is created. If scientists, engineers and management are recruited from abroad, chances are that knowledge and technology capabilities will not spill-over to local actors. On the other hand, a brain drain of biotechnologists, agronomists and engineers from LDCs to developed countries, jeapordizes the establishment of science and technology-based bioeconomies.

The UNCTAD report sees the importance of these movements of 'brain drain' and 'brain gain', and their impacts on the knowledge stock of LDCs.

International migration of skilled persons in principle contributes to building the recipient countries’ skills endowment, while entailing a loss in the origin country’s stock of human capital. The most important issue for countries’ long-term development is the net effect of migratory flows. LDCs have a low skill endowment. Therefore, the international migration of skilled persons from and to those countries can have a strong impact on their human capital stock.

The human capital endowment of an economy is a fundamental determinant of its long-term growth performance, its absorptive capacity and its performance in technological learning. It is also a requirement for the effective working of trade, FDI, licensing and other channels as means of technology diffusion. In LDCs the major migratory flow of qualified professionals is that of skilled people settling mainly in developed countries.The costs of emigration can in principle be (partly) offset by other developments, including higher enrolment in tertiary education, an increase in remittances and the eventual brain gain through the return of emigrants, brain circulation by means of temporary return, and creation of business and knowledge linkages between emigrants and home countries (leading to technology flows, investment, etc.). These increased flows in knowledge, investment and trade are more likely to occur in the case of industries producing tradable products than those producing non-tradables.

But the UNCTAD warns that these positive effects of 'brain circulation' are not likely to occur in LDCs, for clear reasons:

Many of those positive effects, however, occur only once countries have reached a certain level of development and income growth. That implies the existence of considerably improved economic conditions in home countries, which provide incentives for temporary or permanent return of emigrants and for the establishment of stronger knowledge and economic flows. Moreover, an improved domestic environment entails lower out-migration pressure. That situation is obviously not the one prevailing in LDCs. Those countries are therefore the most likely to suffer from brain drain, rather than benefiting from brain circulation, brain gain or the other positive effects possibly associated with emigration.

For the LCDs, three main features of skilled emigration have been observed since the 1990s:

- Emigration rates were generally high among tertiary-educated persons by international standards, with an unweighted mean for LDCs of 21 per cent in 2000 (much higher than for all all lower-middle-income and low-income countries)

- There was considerable variation in the total rates of emigration among tertiary–educated persons by and within country groups among the LDCs. They were close to 25 per cent (unweighted) in the island LDCs, West Africa and East Africa, and lowest in the generally more populated Asian LDCs (6 per cent), with Central Africa falling in between (14 per cent).

- Out-migration among tertiary-educated persons from LDCs to OECD countries has accelerated over the last 15 years. The unweighted mean emigration rate rose from 16 per cent in 1990 to 21 per cent 10 years later. That intensification of emigration among skilled persons was much stronger than among all emigrants from LDCs.

The UNCTAD formulates policy recommendations on how best to deal with these migration flows, in such a way that they limit the impact on the knowledge-base of the LDCs.

5. 'Knowledge aid'

The classic saying goes that it's better to teach a man how to fish, than to throw him a fish whenever he's hungry. Likewise, the justification for foreign aid is often articulated only on the basis of pressing economic, social and political objectives (e.g. food aid, with less attention for teaching people how to grow more food).

So more fundamentally, aid can help to build up the knowledge resources and knowledge systems of LDCs. This is particularly important for the LDCs because their level of technological development is so low and technological learning through international market linkages is currently weak.

Aid can play an important role in developing a minimum threshold level of competences and learning capacities which will enable LDCs to rectify that situation. Indeed, the provision of more knowledge aid, if directed towards the right areas and appropriate modalities, may be the key to aid effectiveness.The UNCTAD defines 'knowledge aid' as aid that supports knowledge accumulation within partner countries.

Knowledge aid can be provided in two ways:

- either through supplier executed services, where, for example, donors provide consultants who advise on, or design and develop, projects, programmes and strategies

- or through strengthening the knowledge resources and knowledge systems of the partners themselves, a process which may be called 'partner learning'

Aid to build STI capacities

Aid to build science, technology and innovation capacity is a particular form of knowledge aid and should support:

- the development of productive capacities through building up domestic knowledge resources and domestic knowledge systems

- the development of governmental capacities to design and implement STI policies

A brief overview of the numbers for 2003-2005 for all LDCs combined show that knowledge aid has captured a marginal share of the overall aid budgets:

- aid for agricultural research equal to only $22 million per year

- only $62 million for vocational training

- a meagre $12 million per year for agricultural education and training

- $9 million per year for agricultural extension

- development of advanced technical and managerial skills received only $18 million per year

- disbursements for what is described in the reporting system as “technological research anddevelopment” – which covers industrial standards, quality management, metrology, testing, accreditation and certification – received only $5 million per year during 2003–2005.

emphasized in the routine poverty alleviation programmes, namely agricultural research and extension, aid commitments to LDCs have actually fallen rather than risen since the late 1990s. Compare this with the annual technical cooperation commitments to improve 'governance' (in the widest sense). In 2003–2005 these were $1.3 billion. Agricultural extension received $12 million...

As the UNCTAD report simply notes: it will be impossible to ensure 'good governance' if States don't have a productive and viable economy to build on and to draw incomes from.

The authors make some policy recommendations that could help deal with the problem of the lack of aid going to knowledge, technology and science. The recommendations are offered per sector:

Agricultural R&D

Although agriculture is the major livelihood in the LDCs, the current agricultural research intensity – expenditure on agricultural research as a share of agricultural GDP – is only 0.47 per cent. That compares with 1.7 per cent in other developing countries. The LDC agricultural research intensity is far below the 1.5 to 2 per cent recommended by some international agencies. Moreover, the low level reflects a serious decline in the agricultural research intensity in the LDCs since the late 1980s, when the figure stood at 1.2 per cent.

Non-agricultural technological learning and innovation

Agriculture is still the major source of employment and livelihood in the LDCs, but the employment transition which they are undergoing means that this position is not tenable if development partners wish to reduce poverty sustainably and substantially.

One important recommendation for the non-agricultural sector is that donor-supported physical infrastructure projects should all include components use the construction process to develop domestic design and engineering capabilities.

In addition, there is a need for public support for enterprise-based technological learning, which should be in the form of grants or soft loans for investment in the relevant types of knowledge assets. Such support should be undertaken as a costsharing public–private partnership for creating public goods, particularly in relation to the development of design and engineering skill through enterprise-based practice. These STI capacity-building activities could be particularly useful if they are linked to value chain development schemes, FDI linkage development and the facilitation of South–South cooperation.

“Aid for Trade”

There is widespread support for scaling up this kind of aid amongst LDCs. Experiences show that technological learning and innovation are central to successful cases of trade development. However, technological learning and innovation have been conspicuously absent from past efforts to provide Aid for Trade. They are neglected within current attempts to define the scope of the subject.

It is recommended that aid for technological learning and innovation for tradable sectors be a key component of Aid for Trade, and LDC development partners should adopt best practices which are evident from successful cases of trade development, such as palm oil in Malaysia and Nile perch in Uganda. Note that environmentalists have condemned precisely these two examples as cases of how trade development can destroy the most basic foundations of sustainability.

Conclusion

By way of conclusion, we can say that many insights and recommendations from the UNCTAD report can be readily applied to the development of strategies with which LDCs can approach the opportunities of the emerging bio-economy. Such an new, green economy holds the potential to boost local development and allows poor countries to leapfrog beyond the fossil fuel era. But in order to transit towards this sustainable, biobased economy, investments in knowledge and technology are urgently needed. The sector is highly competitive, and mere comparative advantages (agro-ecological resources) won't suffice for these countries to participate in it in a meaningful way.

Biopact readers know that we have often stressed the need for appropriate tech transfer strategies in the biofuels sector. Brazil has gone some way in this respect, and has forged South-South collaboration efforts by linking its own expert agricultural research organisations with those of poor countries. There's also France's bioenergy knowledge-exchange initiative, which couples students from the country to collegues in developing countries. But overall, these initiatives remain marginal. A much more urgent and broader effort is needed to create robust ways for the North to help the South strengthen its capacities to boost investments in STI.

For example, policies in LDCs must ensure that when foreign companies from highly developed countries enter the sector in poor countries, technology and knowledge transfers as well as opportunities for joint-ventures occur that allow local players to acquire expertise and technological capabilities. Else, biofuels may become just another 'resource grab'.

On the other hand, States need to craft policies and infrastructures that make it possible for local players to 'absorb' knowledge (it's a two-way process). Finally, as we have stressed earlier, national and international policy frameworks and investments in STI in developing countries are crucial for the bioenergy sector to flourish in a genuinely sustainable way.

Professor John Mathews, an expert on STI and knowledge-driven industrial development strategies has writen in-depth analyses on the subject as it relates to the biofuels sector in developing countries (for an example, see 'A Biofuels Manifesto').

On an ending note, consider this. Those of us who understand the complex and multi-dimensional concept of 'sustainable development' will admit that such an understanding requires study, exchanges between thinkers, scientists and policy makers. Don't we all want the people in the South - who are often merely the passive subjects of such concepts - to acquire the capacities needed to develop their own notions of sustainability and the skills to implement them?

References:

UNCTAD: The Least Developed Countries Report, 2007. Knowledge, technical learning and innovation for development [*.pdf, full report] - July 2007.

UNCTAD: The Least Developed Countries Report, 2007 [*.pdf, summary] - July 19, 2007.

UNCTAD: The Least Developed Countries Report, 2007, Highlights - July 19, 2007.

John Mathews, A Biofuels Manifesto: Why Biofuels Industry Creation Should be 'Priority Number One' for the World Bank and for Developing Countries [*.pdf] - September 2006.

--------------

--------------

PetroChina, one of China's biggest oil companies, aims to invest RMB 300 million (€28.7/US$39.6m) in biofuel production development plans. A special fund is also going to be jointly set up by PetroChina and the Ministry of Forestry to reduce carbon emissions. Two thirds of the total investment will be channeled into forestry and biofuel projects in the provinces of Sichuan, Yunnan and Hebei, the remainder goes to creating a China Green Carbon Foundation, jointly managed by PetroChina and the State Forestry Administration.

PetroChina, one of China's biggest oil companies, aims to invest RMB 300 million (€28.7/US$39.6m) in biofuel production development plans. A special fund is also going to be jointly set up by PetroChina and the Ministry of Forestry to reduce carbon emissions. Two thirds of the total investment will be channeled into forestry and biofuel projects in the provinces of Sichuan, Yunnan and Hebei, the remainder goes to creating a China Green Carbon Foundation, jointly managed by PetroChina and the State Forestry Administration.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Links to this post:

Create a Link

<< Home