DR Congo: Chinese company to invest $1 billion in 3 million hectare oil palm plantation

To some it may sound like the ultimate nightmare, others see a great sign of hope: a Chinese company, ZTE International, is to invest US$1 billion in an immense 3 million hectare oil palm plantation in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) with the aim to produce biofuels. The vast Central-African country formerly known as Zaire is a potential bioenergy 'superpower' which could supply a large part of the world's fuel needs. But it faces some hard choices. Congo is home to the world's second largest undisturbed tropical rainforest, an invaluable hotspot of biodiversity and carbon sink that is increasingly under pressure from (illegal) logging operations. A rush into the biofuel sector could threaten these ecosystems further. On the other hand, if managed carefully, the biofuels opportunity could help lift the Congolese people - who rank amongst the poorest in the world - out of dire poverty and revive the DRC's economy.

Congo is only slowly waking up from the nightmare it experienced over the past decades. Everything has to be rebuild, from the state apparatus and the economy to social and health services, from schools and hospitals to roads and railroads. In this immense country the size of Western Europe there are only 300 kilometres of paved roads...

But things are changing fast in the nation of 60 million. The relative macro-economic and political stability brought about by the new government is attracting investors who spot countless business opportunities. The economy is growing at a rate of 6 to 7 per cent annually, inflation is under control, attractive investment rules are in place and millions are looking for a job that will take them out of the informal economy and out of poverty (80% of Congolese live on less than a dollar per day). But here too, there is a huge need for reconstruction and governance: the banking sector is in ruins, transport infrastructures and ports need to be rebuild and corruption is rampant.

Meanwhile, media in Kinshasa have become extatic and dithyrambic on hearing the news of the Chinese biofuels investment, with headlines boasting that Congo will become the new 'Saudi Arabia of the tropics'. They see the return of foreign investors and their immediate interest in the bioenergy sector as a sign of positive change, a symbol of the fact that the war is over and that stability and prosperity are about to arrive. Others are far more critical and point to the great risks the sector represents to Congo's environment.

An analyst writing in Kinshasa's Le Potentiel (*French) sums up the reasons as to why he thinks biofuels are the way forward for the DRC:

energy :: sustainability :: ethanol :: biodiesel :: biomass :: bioenergy :: biofuels :: oil palm :: deforestation :: poverty alleviation :: energy security :: Democratic Republic of Congo ::

energy :: sustainability :: ethanol :: biodiesel :: biomass :: bioenergy :: biofuels :: oil palm :: deforestation :: poverty alleviation :: energy security :: Democratic Republic of Congo ::

Projections show that, even with a rapidly growing population (currently growing at 3% annually), the country has the technical potential to both supply its own population and that of Central-Africa as a whole with food, fuel and fiber, and to produce an excess in the form of bioenergy that could replace up to a tenth of the world's oil demand by 2030, without endangering the rainforest or the food security of people. Obviously, such technical assessments say nothing about the reality on the ground (e.g. Congo currently is a net food importer). And the question as to whether this vast potential will be exploited in a sustainable and socially acceptable way is a matter of governance, policy, trade rules, development assistance, investment approaches and business practises.

Meeting local demand first

The Chinese project will be implemented in the Equateur and Bandundu provinces, in the Province Orientale and in part of West-Kasaï.

In first instance the Chinese company will satisfy local demand for oil palm. Despite its vast potential, Congo currently imports a relatively small quantity of 15,000 tonnes per year, mainly due to the breakdown of logistical chains that are supposed to bring the product from the hinterland to the capital. Current oil palm production stands at around 240,000 tonnes, with demand expected to grow to 465,000 tonnes in 2010 and 540,000 tonnes in 2015.

When the palms for the 3 million hectares are planted this and next year, and reach full maturity 5 years later (in 2013) the plantations would yield around 12 million tonnes of oil (at 4 tonnes per hectare), easily meeting local demand. The excess of around 11.5 million tonnes would be used for the production of biofuels (or for human consumption, depending on the market situation and the reality of peak oil, which should become apparent by that time).

Export potential

According to the latest IEA figures (2004) Congo consumes around 390,000 tonnes of gasoline and diesel per year, an equivalent of around 2.3 million barrels annually or 6,400 bpd. Total oil products demand stands at 8,200 bpd. In other words, this vast country of 60 million inhabitants consumes in a year what the U.S. consumes in less than one minute... Estimating demand for oil products in Congo to grow at around 5 per cent per annum, by 2013, the country would require approximately 12,702 bpd. Such an amount of oil equivalent energy can be obtained from around 193,000 tonnes of palm oil. Substracting this from the 11.5 million tonnes means that around 11.3 million tonnes are available for exports.

In short, the Chinese project alone could meet rapidly growing local demand for palm oil, replace all of Congo's petroleum products with locally produced biofuels, and result in an excess of 11.3 million tonnes of palm oil or 67.8 million barrels of oil equivalent biofuels per year for export. This comes down to 186,000 barrels of oil equivalent per day, roughly the output of an oil exporting country like Bahrain. This single Chinese project could export enough the meet all the oil needs of a highly developed country like New Zealand or Ireland.

Note that palm plantations yield a tremendous amount of biomass, currently not used for the production of liquid biofuels. The 4 tonnes of oil that are expected from an average hectare of trees represents a fraction of the total stream of biomass residues - fronds, trunks, fruit press cakes, fibers, empty fruit bunches, kernel shells and kernel meal, and palm oil mill effluent -, which contains up to three times more energy than the palm oil and the palm kernel oil produced by a mill.

Technically speaking, if second generation biofuel production technologies that can tap into these large biomass residue flows become viable, the liquid fuel output of a hectare of oil palm trees could be doubled. Alternatively, the biomass obtained from palm processing activities can already be used for the production of green electricity and biogas with currently existing technologies. It will be interesting to see how ZTE International integrates these new forms of exploiting oil palm residues.

Finally, it is not clear whether the Chinese project involves planting high-yield clonal varieties that have been developed over the past few years. In 2003, a Malaysian company succeeded in creating a clone that yields up to 30% more oil.

Social and environmental sustainability

This type of mega-projects presents an obvious threat to the Congo basin rainforest that is already under pressure from (illegal) logging. In all countries with a large palm oil sector - Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, Colombia - the establishment of industrial-scale plantations has gone at the expense of forests. Recent attempts to make the sector more sustainable - through bodies like the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil - are encouraging, but the simple fact remains that forests go when palm oil arrives.

Oil palms are perennial crops that can only be exploited profitably in monocultural systems. Once they are planted, they are kept in place for 25 years after which they are replaced, often with higher yielding varieties. Monocultures imply the use of fertilizers and pesticides even though organic farming techniques are being researched. Attempts at integrating oil palm on a commercial scale in small farms that grow a diversity of crops are largely unsuccessful. There is an unbridgeable gap between traditional, cottage palm oil production and industrial-scale exploitation based on vast plantations. There is no middle ground.

Large palm oil projects have complex social consequences that can be interpreted as positive or negative, depending on which perspective one is inclined to take. In many cases, smallholders see the sector as their best shot at staying out of poverty, but the truth is that they often don't have any other economic opportunity available. In a country like Indonesia, up to 50% of all palm fruit producers are small farmers with less than 5 hectares, the rest is made up of estates owned by industrial groups. The expansion of palm plantations for biofuels is hailed by several developing country governments as a historic chance to bring jobs to millions of unemployed rural people and small farmers.

Moreover, the palm oil industry 'opens up' remote and often marginal rural areas by bringing new infrastructures (roads, canals, energy and irrigation infrastructures) and by creating new markets and access to new products. This often radically changes the local economy and commerce. It is not certain whether these impacts are as beneficial as the oil palm sector often wants us to believe, because they clearly increase pressures on the local environment.

In any case, behind this classic logic that depicts the palm sector as largely beneficial from a social and economic perspective, hides a less pleasant tradition: that of putting local communities in front of a choice they might not want to make. This choice is often as banal as the option of becoming palm oil farmers and turning land into plantations, or to face political and economic marginality and often outright violence. There are numerous cases of indigenous people being forcibly displaced to make way for palm estates.

A local newspaper in Kinshasa is worried that in the future certain forest-dwelling populations might be forced out of their environment because of the expansion of palm plantations. It cites an example which indicates that this has already happened in the context of logging operations. And as we know, palm oil often moves in after loggers have paved the way:

In a country like Congo, which once used to be the world's second largest palm oil producer (in the 1960s), the extensive experience and history with palm production in other tropical countries can be used as the basis for the creation of robust policies that must ensure socially acceptable forms of production. But Congo comes out of a situation of total state collapse, so it will need all the help it can get to devise strong governance structures and strategies. If it succeeds in taking a pragmatic and wise set of policies, the country's potential for biofuel production might indeed bring prosperity to those who need it most.

Palm oil does not necessarily have to be environmentally and socially destructive. Some organisations have been calling for a complete 'moratorium' on biofuels made from palm oil, but this may not be the smartest approach towards more sustainability. Earlier, we referred to an interesting analysis which showed that a hypothetical import ban by the West on fuels made from the most productive energy crop would be far more disastrous for the environment than stimulating the production of eco-friendlier palm oil, even if it means expanding the sector.

The main reasons:

(1) palm oil employs millions of small farmers; taking away their livelihoods without providing realistic alternatives results in far more environmental destruction (poverty and correlated high fertility rates are the key drivers of deforestation and environmental degradation);

(2) Asian demand is growing rapidly and only a sustainability offensive launched by the EU or by an international body can bring a counter-weight; in order to kickstart this drive towards eco-friendlier production, more investments are needed in the sector, not less. Palm oil producers might decide to export to a country like China, where sustainability criteria for imported oil are non-existent and where demand is insatiable; an international effort is needed to create a consensus on sustainable production and the EU can preventively invest in sustanability policies and frameworks for the sector in a country like Congo;

(3) in the specific case of Congo, palm oil can bring in much needed billions that will be required for the reconstruction of the state, for economic development and for poverty alleviation on a vast scale; palm oil may seem like a quick-fix, but in fact, if the vast rural populations of Congo are not soon helped economically and provided with formal employment, the pressures they exert on the environment will be enormous. The example of Malaysia shows that a single sector like palm oil can contribute substantially to the health of the economy as a whole;

(4) further, and related to the potential for economic growth: Congo faces a demographic explosion that can only be slowed down by fast economic growth, and growth the effects of which can be felt by rural people. Poverty and fertility rates are strictly correlated; if palm oil can contribute to significantly increasing the incomes of millions of Congolese farmers, then there would be indirect demographic effects. UN projections show that, for Congo, the difference between a low population growth scenario and a medium and high one means the difference between a population of 160 million or 210 million in 2050. Palm oil can help work towards the low scenario, which would be beneficial for the people and the environment at large;

(5) finally, in a best-case scenario, the establishment of a palm oil sector in Congo will bring infrastructures and access to new markets and products for rural populations. This will allow them, for the first time, to rely on agricultural production techniques that require less land and yield more. Access to modern inputs (fertilizers, pesticides, quality seeds, etc) are absolutely primordial. Currently, subsistence agriculture in the African country is highly unsustainable and requires a constant expansion of land; modest modernisation could turn this situation around. Both the material infrastructures and the funds to allow such interventions could come from an export-driven palm oil sector. Access to new markets for agricultural products would boost rural incomes and reduce poverty - the key driver in environmental destruction. 70 per cent of the DRC's population currently makes a living in agriculture.

Notwithstanding these general observations, the developed world has an obligation to assist a country like Congo with devising policy frameworks and governance structures that limit the negative environmental impacts of the palm oil sector. This would be smarter than a simple ban on palm oil products.

Moreover, the EU and other biofuel importing countries will have to devise a subtle set of social and environmental sustainability criteria that allow a country like Congo to produce and export biofuels, but that encourages it to invest radically in sustainability. Such criteria can not become a new set of trade barriers; farm subsidies in Europe and the U.S. as well as tariffs and non-tariff barriers are already having disastrously negative consequences for the developing world - so much so that a country like Congo is actually a net food importer, whereas technically it should be a major agricultural producer and exporter. Sustainability criteria must go hand in hand with trade reform.

Avoided deforestation

At the same time, Congo is analysing whether a concept like 'avoided deforestation' would work to its advantage. This concept is based on the idea that developing countries should be compensated in one form or another to preserve their rainforests, which are valuable carbon sinks. If the carbon sequestered and cycled in these forests receives a value that can be converted into cash (e.g. via international carbon markets), countries like Congo would have a major incentive to reduce deforestation. The need for palm oil plantations which require deforestation would disappear because a viable alternative presents itself under the form of carbon trading.

The way in which such 'avoided deforestation' schemes will be implemented is currently being researched, but they are quite promising. On the other hand, they also represent risks in that they are top-down schemes that do not directly and automatically benefit the people on the ground who make a living from forests and from deforestation, such as the many small farmers whose susbsistence farming techniques force them to slash and burn their way through forest. Moreover, it is not clear what the effect of high oil prices would be on the feasibility of avoided deforestation schemes. If 'peak oil' becomes real and prices skyrocket, it might be more attractive for forest-rich developing countries to produce biofuels, which bring energy security in a very tangible form. Finally, biofuel production brings incomes to rural populations in a direct and straightforward way, because they are at the basis of the production scheme.

In short, biofuels follow a 'bottom-up' pathway partly controlled by small farmers (certainly in the case of palm oil), whereas avoided deforestation represents a 'top-down' scheme of which it is not sure that the funds, managed by bureaucrats and states, will ever reach the people who are entitled to them.

China's new plantation rules

So far, Congo's immeasurable wealth in natural resources has been a cause of recurring colonial and postcolonial conflicts. The question is whether the new government will succeed in turning this dark history around. Some think China will play a decisive role in determining the outcome. The country's growing presence in Africa and in Congo can be seen as a stabilizing force, while others perceive it as a new round of colonialism.

In this context, environmentalists have accused the PRC of destroying the world's remaining tropical forests to fuel its own needs for wood and agricultural products. The country is clearly sensitive to the critiques, so much so that it recently unveiled a draft sustainable forestry handbook for Chinese companies operating overseas.

The guidelines call for a ban on illegal logging and clearing of natural forests for plantations. The manual, which was announced last year, has been distributed to China's 31 provinces, its forestry department, and various industry groups, and will soon go out to officials in 333 cities and 2,862 counties, according to a statement posted on the Forestry Ministry Web site.

Image courtesy of Gazopalm.

References:

Le Potentiel (via AllAfrica): Congo-Kinshasa: Biocarburant - La RDC doit faire le choix entre le palmier elaeis et le jatropha curcas - July 10, 2007 (alternative location, here at Congoforum).

La Conscience (Kinshasa) (via Congoforum): La RD Congo est potentiellement capable de devenir l'un des plus grands producteurs du monde - July 05, 2007.

Biopact: Fuel shortages in the heart of Africa - biofuels to the rescue? - April 17, 2007.

Biopact: New Congo government identifies bioenergy as priority for industrialisation - May 03, 2007

Mongabay: China calls for sustainable logging by Chinese firms overseas - July 11, 2007.

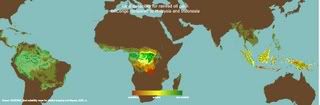

Land suitability for oil palm in Congo, compared to Malaysia and Indonesia (click to enlarge)

From 1996 to 2002, the former Belgian colony was at the center of a brutal continental war that took the lives of an estimated 4.5 million Congolese people - the deadliest (and most underreported) conflict since the Second World War. Last year, with the aid of the international community, the country held its first democratic elections since independence in 1960, bringing Joseph Kabila to power. In the east of the country, the war over mineral resources rages on, despite the presence of a large UN peace keeping force.Congo is only slowly waking up from the nightmare it experienced over the past decades. Everything has to be rebuild, from the state apparatus and the economy to social and health services, from schools and hospitals to roads and railroads. In this immense country the size of Western Europe there are only 300 kilometres of paved roads...

But things are changing fast in the nation of 60 million. The relative macro-economic and political stability brought about by the new government is attracting investors who spot countless business opportunities. The economy is growing at a rate of 6 to 7 per cent annually, inflation is under control, attractive investment rules are in place and millions are looking for a job that will take them out of the informal economy and out of poverty (80% of Congolese live on less than a dollar per day). But here too, there is a huge need for reconstruction and governance: the banking sector is in ruins, transport infrastructures and ports need to be rebuild and corruption is rampant.

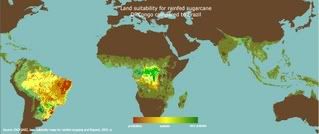

Land suitability for sugarcane in Congo, compared to Brazil (click to enlarge)

When it comes to biofuels, the Congolese are gradually beginning to understand the worldchanging prospect that in a post-oil era, their country, together with Brazil, will largely determine the energy security of the world. The DRC's new government has just recently established an interministerial commission on biofuels to assess the complex opportunities and the many risks of this future. Policy work is urgently needed. The EU is thinking of assisting the country with impact and sustainability analyses.Meanwhile, media in Kinshasa have become extatic and dithyrambic on hearing the news of the Chinese biofuels investment, with headlines boasting that Congo will become the new 'Saudi Arabia of the tropics'. They see the return of foreign investors and their immediate interest in the bioenergy sector as a sign of positive change, a symbol of the fact that the war is over and that stability and prosperity are about to arrive. Others are far more critical and point to the great risks the sector represents to Congo's environment.

An analyst writing in Kinshasa's Le Potentiel (*French) sums up the reasons as to why he thinks biofuels are the way forward for the DRC:

The revival of our economy largely depends on access to energy and in particular to petroleum products. One of the largest obstacles to the development of our industrial and agricultural sectors has always been the lack of energy. During the past 3 decades the totality of petroleum products has been imported, draining our country's treasury and weakening its trade balance. The future of our economy is inconceivable without the national production of biofuels, in particular biodiesel.The author then sketches two scenarios in an oil-dependent future in which prices for petroleum are as high as today, and concludes that Congo better invest in biofuels rightaway, which allows for local control over energy resources, price stability and energy security.

1. Either supplies of petroleum products can no longer be guaranteed by the State with a collapse of all economic developments as a consequence, which will further increase and generalise poverty: 80% of the Congolese people live on less than a dollar a day.When it comes to the technical biofuels potential of Congo, we can be brief: the country has Africa's largest base of potential arable land, some 167 million hectares of non-forest land (roughly as much as all countries of Western Europe combined), it has the world's largest expanse of agro-ecologically highly suitable land for crops like sugarcane and oil palm (see maps), besides having a vast potential for most other tropical (energy) crops such as soybeans, sorghum, cassava, grasses and energy trees. Currently, the country has around 4.7% of its arable land base under cultivation:

2. Or demand for oil can be met somehow with the support of the private sector, and a certain degree of industrial and agricultural progress can be expected, but the country would suffocate financially, see its debts explode and be devoid of means to invest in its enormous agricultural potential and in the mining sector.

No matter which scenario is most likely, no decision maker can be blind to the potential for renewables and biofuels. Today, the production of biofuels is the path our country must undeniably take in order to prevent the further drainage of our treasury resulting from oil imports.

energy :: sustainability :: ethanol :: biodiesel :: biomass :: bioenergy :: biofuels :: oil palm :: deforestation :: poverty alleviation :: energy security :: Democratic Republic of Congo ::

energy :: sustainability :: ethanol :: biodiesel :: biomass :: bioenergy :: biofuels :: oil palm :: deforestation :: poverty alleviation :: energy security :: Democratic Republic of Congo ::Projections show that, even with a rapidly growing population (currently growing at 3% annually), the country has the technical potential to both supply its own population and that of Central-Africa as a whole with food, fuel and fiber, and to produce an excess in the form of bioenergy that could replace up to a tenth of the world's oil demand by 2030, without endangering the rainforest or the food security of people. Obviously, such technical assessments say nothing about the reality on the ground (e.g. Congo currently is a net food importer). And the question as to whether this vast potential will be exploited in a sustainable and socially acceptable way is a matter of governance, policy, trade rules, development assistance, investment approaches and business practises.

Meeting local demand first

The Chinese project will be implemented in the Equateur and Bandundu provinces, in the Province Orientale and in part of West-Kasaï.

In first instance the Chinese company will satisfy local demand for oil palm. Despite its vast potential, Congo currently imports a relatively small quantity of 15,000 tonnes per year, mainly due to the breakdown of logistical chains that are supposed to bring the product from the hinterland to the capital. Current oil palm production stands at around 240,000 tonnes, with demand expected to grow to 465,000 tonnes in 2010 and 540,000 tonnes in 2015.

When the palms for the 3 million hectares are planted this and next year, and reach full maturity 5 years later (in 2013) the plantations would yield around 12 million tonnes of oil (at 4 tonnes per hectare), easily meeting local demand. The excess of around 11.5 million tonnes would be used for the production of biofuels (or for human consumption, depending on the market situation and the reality of peak oil, which should become apparent by that time).

Export potential

According to the latest IEA figures (2004) Congo consumes around 390,000 tonnes of gasoline and diesel per year, an equivalent of around 2.3 million barrels annually or 6,400 bpd. Total oil products demand stands at 8,200 bpd. In other words, this vast country of 60 million inhabitants consumes in a year what the U.S. consumes in less than one minute... Estimating demand for oil products in Congo to grow at around 5 per cent per annum, by 2013, the country would require approximately 12,702 bpd. Such an amount of oil equivalent energy can be obtained from around 193,000 tonnes of palm oil. Substracting this from the 11.5 million tonnes means that around 11.3 million tonnes are available for exports.

In short, the Chinese project alone could meet rapidly growing local demand for palm oil, replace all of Congo's petroleum products with locally produced biofuels, and result in an excess of 11.3 million tonnes of palm oil or 67.8 million barrels of oil equivalent biofuels per year for export. This comes down to 186,000 barrels of oil equivalent per day, roughly the output of an oil exporting country like Bahrain. This single Chinese project could export enough the meet all the oil needs of a highly developed country like New Zealand or Ireland.

Cutting bunches of palm fruit at the plantations of Busira Lomami, eastern Congo.

Note that palm plantations yield a tremendous amount of biomass, currently not used for the production of liquid biofuels. The 4 tonnes of oil that are expected from an average hectare of trees represents a fraction of the total stream of biomass residues - fronds, trunks, fruit press cakes, fibers, empty fruit bunches, kernel shells and kernel meal, and palm oil mill effluent -, which contains up to three times more energy than the palm oil and the palm kernel oil produced by a mill.

Technically speaking, if second generation biofuel production technologies that can tap into these large biomass residue flows become viable, the liquid fuel output of a hectare of oil palm trees could be doubled. Alternatively, the biomass obtained from palm processing activities can already be used for the production of green electricity and biogas with currently existing technologies. It will be interesting to see how ZTE International integrates these new forms of exploiting oil palm residues.

Finally, it is not clear whether the Chinese project involves planting high-yield clonal varieties that have been developed over the past few years. In 2003, a Malaysian company succeeded in creating a clone that yields up to 30% more oil.

Social and environmental sustainability

This type of mega-projects presents an obvious threat to the Congo basin rainforest that is already under pressure from (illegal) logging. In all countries with a large palm oil sector - Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, Colombia - the establishment of industrial-scale plantations has gone at the expense of forests. Recent attempts to make the sector more sustainable - through bodies like the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil - are encouraging, but the simple fact remains that forests go when palm oil arrives.

Oil palms are perennial crops that can only be exploited profitably in monocultural systems. Once they are planted, they are kept in place for 25 years after which they are replaced, often with higher yielding varieties. Monocultures imply the use of fertilizers and pesticides even though organic farming techniques are being researched. Attempts at integrating oil palm on a commercial scale in small farms that grow a diversity of crops are largely unsuccessful. There is an unbridgeable gap between traditional, cottage palm oil production and industrial-scale exploitation based on vast plantations. There is no middle ground.

Large palm oil projects have complex social consequences that can be interpreted as positive or negative, depending on which perspective one is inclined to take. In many cases, smallholders see the sector as their best shot at staying out of poverty, but the truth is that they often don't have any other economic opportunity available. In a country like Indonesia, up to 50% of all palm fruit producers are small farmers with less than 5 hectares, the rest is made up of estates owned by industrial groups. The expansion of palm plantations for biofuels is hailed by several developing country governments as a historic chance to bring jobs to millions of unemployed rural people and small farmers.

Moreover, the palm oil industry 'opens up' remote and often marginal rural areas by bringing new infrastructures (roads, canals, energy and irrigation infrastructures) and by creating new markets and access to new products. This often radically changes the local economy and commerce. It is not certain whether these impacts are as beneficial as the oil palm sector often wants us to believe, because they clearly increase pressures on the local environment.

In any case, behind this classic logic that depicts the palm sector as largely beneficial from a social and economic perspective, hides a less pleasant tradition: that of putting local communities in front of a choice they might not want to make. This choice is often as banal as the option of becoming palm oil farmers and turning land into plantations, or to face political and economic marginality and often outright violence. There are numerous cases of indigenous people being forcibly displaced to make way for palm estates.

A local newspaper in Kinshasa is worried that in the future certain forest-dwelling populations might be forced out of their environment because of the expansion of palm plantations. It cites an example which indicates that this has already happened in the context of logging operations. And as we know, palm oil often moves in after loggers have paved the way:

The Mbuti (Efe) pygmees who live in the Ituri forest have been removed from their land since the 1990s and have been forced to give up their traditional livelihoods, so that European and Malaysian forestry companies could take their place. Since the middle of 2006, the construction of new roads and tracks through their forest has led to the destruction of the natural habitat of the Efe who have become disoriented and whose communities have disintegrated.International perspectives and support

In a country like Congo, which once used to be the world's second largest palm oil producer (in the 1960s), the extensive experience and history with palm production in other tropical countries can be used as the basis for the creation of robust policies that must ensure socially acceptable forms of production. But Congo comes out of a situation of total state collapse, so it will need all the help it can get to devise strong governance structures and strategies. If it succeeds in taking a pragmatic and wise set of policies, the country's potential for biofuel production might indeed bring prosperity to those who need it most.

Palm oil does not necessarily have to be environmentally and socially destructive. Some organisations have been calling for a complete 'moratorium' on biofuels made from palm oil, but this may not be the smartest approach towards more sustainability. Earlier, we referred to an interesting analysis which showed that a hypothetical import ban by the West on fuels made from the most productive energy crop would be far more disastrous for the environment than stimulating the production of eco-friendlier palm oil, even if it means expanding the sector.

The main reasons:

(1) palm oil employs millions of small farmers; taking away their livelihoods without providing realistic alternatives results in far more environmental destruction (poverty and correlated high fertility rates are the key drivers of deforestation and environmental degradation);

(2) Asian demand is growing rapidly and only a sustainability offensive launched by the EU or by an international body can bring a counter-weight; in order to kickstart this drive towards eco-friendlier production, more investments are needed in the sector, not less. Palm oil producers might decide to export to a country like China, where sustainability criteria for imported oil are non-existent and where demand is insatiable; an international effort is needed to create a consensus on sustainable production and the EU can preventively invest in sustanability policies and frameworks for the sector in a country like Congo;

(3) in the specific case of Congo, palm oil can bring in much needed billions that will be required for the reconstruction of the state, for economic development and for poverty alleviation on a vast scale; palm oil may seem like a quick-fix, but in fact, if the vast rural populations of Congo are not soon helped economically and provided with formal employment, the pressures they exert on the environment will be enormous. The example of Malaysia shows that a single sector like palm oil can contribute substantially to the health of the economy as a whole;

(4) further, and related to the potential for economic growth: Congo faces a demographic explosion that can only be slowed down by fast economic growth, and growth the effects of which can be felt by rural people. Poverty and fertility rates are strictly correlated; if palm oil can contribute to significantly increasing the incomes of millions of Congolese farmers, then there would be indirect demographic effects. UN projections show that, for Congo, the difference between a low population growth scenario and a medium and high one means the difference between a population of 160 million or 210 million in 2050. Palm oil can help work towards the low scenario, which would be beneficial for the people and the environment at large;

(5) finally, in a best-case scenario, the establishment of a palm oil sector in Congo will bring infrastructures and access to new markets and products for rural populations. This will allow them, for the first time, to rely on agricultural production techniques that require less land and yield more. Access to modern inputs (fertilizers, pesticides, quality seeds, etc) are absolutely primordial. Currently, subsistence agriculture in the African country is highly unsustainable and requires a constant expansion of land; modest modernisation could turn this situation around. Both the material infrastructures and the funds to allow such interventions could come from an export-driven palm oil sector. Access to new markets for agricultural products would boost rural incomes and reduce poverty - the key driver in environmental destruction. 70 per cent of the DRC's population currently makes a living in agriculture.

Notwithstanding these general observations, the developed world has an obligation to assist a country like Congo with devising policy frameworks and governance structures that limit the negative environmental impacts of the palm oil sector. This would be smarter than a simple ban on palm oil products.

Moreover, the EU and other biofuel importing countries will have to devise a subtle set of social and environmental sustainability criteria that allow a country like Congo to produce and export biofuels, but that encourages it to invest radically in sustainability. Such criteria can not become a new set of trade barriers; farm subsidies in Europe and the U.S. as well as tariffs and non-tariff barriers are already having disastrously negative consequences for the developing world - so much so that a country like Congo is actually a net food importer, whereas technically it should be a major agricultural producer and exporter. Sustainability criteria must go hand in hand with trade reform.

Avoided deforestation

At the same time, Congo is analysing whether a concept like 'avoided deforestation' would work to its advantage. This concept is based on the idea that developing countries should be compensated in one form or another to preserve their rainforests, which are valuable carbon sinks. If the carbon sequestered and cycled in these forests receives a value that can be converted into cash (e.g. via international carbon markets), countries like Congo would have a major incentive to reduce deforestation. The need for palm oil plantations which require deforestation would disappear because a viable alternative presents itself under the form of carbon trading.

The way in which such 'avoided deforestation' schemes will be implemented is currently being researched, but they are quite promising. On the other hand, they also represent risks in that they are top-down schemes that do not directly and automatically benefit the people on the ground who make a living from forests and from deforestation, such as the many small farmers whose susbsistence farming techniques force them to slash and burn their way through forest. Moreover, it is not clear what the effect of high oil prices would be on the feasibility of avoided deforestation schemes. If 'peak oil' becomes real and prices skyrocket, it might be more attractive for forest-rich developing countries to produce biofuels, which bring energy security in a very tangible form. Finally, biofuel production brings incomes to rural populations in a direct and straightforward way, because they are at the basis of the production scheme.

In short, biofuels follow a 'bottom-up' pathway partly controlled by small farmers (certainly in the case of palm oil), whereas avoided deforestation represents a 'top-down' scheme of which it is not sure that the funds, managed by bureaucrats and states, will ever reach the people who are entitled to them.

China's new plantation rules

So far, Congo's immeasurable wealth in natural resources has been a cause of recurring colonial and postcolonial conflicts. The question is whether the new government will succeed in turning this dark history around. Some think China will play a decisive role in determining the outcome. The country's growing presence in Africa and in Congo can be seen as a stabilizing force, while others perceive it as a new round of colonialism.

In this context, environmentalists have accused the PRC of destroying the world's remaining tropical forests to fuel its own needs for wood and agricultural products. The country is clearly sensitive to the critiques, so much so that it recently unveiled a draft sustainable forestry handbook for Chinese companies operating overseas.

The guidelines call for a ban on illegal logging and clearing of natural forests for plantations. The manual, which was announced last year, has been distributed to China's 31 provinces, its forestry department, and various industry groups, and will soon go out to officials in 333 cities and 2,862 counties, according to a statement posted on the Forestry Ministry Web site.

[The manual] positively guides and standardizes Chinese companies' sustainable forestry activities overseas, promotes the sustainable development of forestry in those countries (and) protects the international image of our government being responsible - Deputy Forestry Minister Li Yucai said in a statementIt remains to be seen how big the gap will be between these guidelines and the actual practises on the ground. The vast Chinese-owned plantation in Congo will offer an interesting case study in this respect. The good thing is that environmentalists now have a quasi-legal basis with which to hold Chinese investors in the forestry and plantation sector in the tropics, accountable.

Image courtesy of Gazopalm.

References:

Le Potentiel (via AllAfrica): Congo-Kinshasa: Biocarburant - La RDC doit faire le choix entre le palmier elaeis et le jatropha curcas - July 10, 2007 (alternative location, here at Congoforum).

La Conscience (Kinshasa) (via Congoforum): La RD Congo est potentiellement capable de devenir l'un des plus grands producteurs du monde - July 05, 2007.

Biopact: Fuel shortages in the heart of Africa - biofuels to the rescue? - April 17, 2007.

Biopact: New Congo government identifies bioenergy as priority for industrialisation - May 03, 2007

Mongabay: China calls for sustainable logging by Chinese firms overseas - July 11, 2007.

--------------

--------------

Together with Chemical & Engineering News' Stephen K. Ritter, the journal Environmental Science & Technology sent Erika D. Engelhaupt to Brazil from where she wrote daily dispatches of news and observations about biofuels research. In particular she focuses on a bioenerrgy research partnership between the American Chemical Society, the Brazilian Chemical Society, and the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (EMBRAPA). Check out her blog.

Together with Chemical & Engineering News' Stephen K. Ritter, the journal Environmental Science & Technology sent Erika D. Engelhaupt to Brazil from where she wrote daily dispatches of news and observations about biofuels research. In particular she focuses on a bioenerrgy research partnership between the American Chemical Society, the Brazilian Chemical Society, and the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (EMBRAPA). Check out her blog.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Links to this post:

Create a Link

<< Home