Pesticides block nature's pathway to produce nitrogen for crops

Many farmers applying pesticides to boost crop yields may instead be contributing to growth problems, scientists report in a new study. According to years of research both in the test tube and, now, with real plants, the team found that artificial chemicals in pesticides – through application or exposure to crops through runoff – disrupt natural nitrogen-fixing communications between crops and soil bacteria. The disruption results in lower yields or significantly delayed growth.

Many farmers applying pesticides to boost crop yields may instead be contributing to growth problems, scientists report in a new study. According to years of research both in the test tube and, now, with real plants, the team found that artificial chemicals in pesticides – through application or exposure to crops through runoff – disrupt natural nitrogen-fixing communications between crops and soil bacteria. The disruption results in lower yields or significantly delayed growth.The research is important in light of the long-term sustainability of world agriculture, which will not only feed rapidly growing populations but also produce fuels that have to replace declining oil resources. If food and fuel production can rely less on pesticides, this is obviously a major environmental benefit.

In their open access paper appearing online this week ahead of the regular publication by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), the five-member team reports that agrichemicals bind to and block connections to specific receptors (NodD) inside rhizobia bacteria living in root nodules in the soil. Rotation legume crops such as alfalfa and soybeans require such interaction to naturally replace nitrogen levels that, in turn, benefit primary market crops like corn grown after legume rotations.

"Agrichemicals are blocking the host plant's phytochemical recruitment signal. In essence, the agrichemicals are cutting the lines of communication between the host plant and symbiotic bacteria. This is the mechanism by which these chemicals reduce symbiosis and nitrogen fixation." - Jennifer E. Fox, lead author, postdoctoral researcher at the Center for Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the University of Oregon.Legume plants secrete chemical signals that recruit the friendly bacteria, which work with the plants to convert atmospheric nitrogen into ammonia that, then, is used as fertilizer by the plants:

bioenergy :: biofuels :: energy :: agriculture :: energy crops :: nitrogen fixation :: pesticides :: legumes :: sustainability ::

bioenergy :: biofuels :: energy :: agriculture :: energy crops :: nitrogen fixation :: pesticides :: legumes :: sustainability :: Fox began the project as a doctoral student with John A. McLachlan, director of the Center for Bioenvironmental Research at Tulane University. She is working at the University of Oregon as a National Institutes of Health and National Research Service Award postdoctoral fellow under Joe Thornton, a professor of biology who focuses on phylogenomics and nuclear receptor genes.

Fox and colleagues began detailing their findings in the journal Nature (2001) and Environmental Health Perspectives (2004), testing more than 50 chemicals, including pentachlorophenol (PCP), in in-vitro assays. The paper in PNAS reports their in-vivo findings using real plants and bacteria.

None of the chemicals used in the research, including PCP, proved to be toxic to either the plants or bacteria, Fox says, "but PCP was unique in that it inhibited both seed germination and nitrogen fixation." More than 20 commonly used agricultural chemicals shared the same mechanism of action as PCP, but with varying amounts of signal disruption.

Fox, McLachlan and colleagues, in their PNAS paper, pointed to two published studies from 2000 that had found significant declines in both crop yield per unit of synthetic nitrogen fertilizer added and also a significant decline in overall symbiotic nitrogen fixation (image, click to enlarge).

The most common explanation for the observations is an overuse of agrichemicals applied to legume crops. That practice sets up "a vicious cycle," Fox said, because it reduces a legume crop's natural need for nitrogen fixation but leaves a shortage of natural nitrogen in the soil for the next year's crop to utilize. Thus, she said, there is the need for yet more fertilizer.

Other reasons, Fox said, have been poor soil quality due to overuse, which strips nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorous from the soil, and to tillage, which interrupts root structures and disturbs the nitrogen-fixing bacteria when soil is turned.

"Our research provides another explanation for declining crop yields," Fox said. "We showed that by applying pesticides that interfere with symbiotic signaling, the overall amount of symbiotic nitrogen fixation is reduced. If this natural fertilizer source is not replaced by increased application of synthetic nitrogen fertilizer, then crop yields are reduced and/or more growing time is needed for these crops to reach the yields obtained by untreated crops. We feel that this is a previously unforeseen factor contributing to declining crop yields."

The researchers say that field-wide experiments now are needed, in addition to tests to determine the exact elements of pesticides that inhibit natural plant-bacteria interaction.

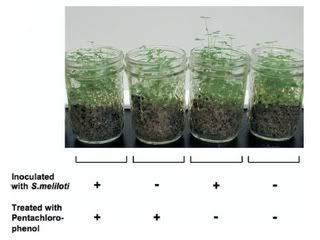

Image: Treatment groups pictured are (from left to right) alfalfa inoculated with S. melioti (bacteria) and treated with pentachlorophenol (pesticide), alfalfa that were not inoculated with S. melioti but were treated with pentachlorophenol, alfalfa inoculated with S. melioti and not treated with any chemicals,and alfalfa that were not inoculated with S. melioti and not treated with any chemicals. Pentachlorophenol treatment significantly reduced plant yield, both when plants were inoculated with S. melioti or left uninoculated.

More information:

Jennifer E. Fox, Jay Gulledge, Erika Engelhaupt, Matthew E. Burow, and John A. McLachlan, "Pesticides reduce symbiotic efficiency of nitrogen-fixing rhizobia and host plants", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, June 4, 2007, DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0611710104

--------------

--------------

According to the Barbados Agricultural Management Company (BAMC), the Caribbean island state has a large enough potential to meet both its domestic ethanol needs (E10) and to export to international markets. BAMC is working with state actors to develop an entirely green biofuel production process based on bagasse and biomass.

According to the Barbados Agricultural Management Company (BAMC), the Caribbean island state has a large enough potential to meet both its domestic ethanol needs (E10) and to export to international markets. BAMC is working with state actors to develop an entirely green biofuel production process based on bagasse and biomass.

1 Comments:

Apply biochar to the fields, and use American GM Seeds. Problem solved, Next.

Post a Comment

Links to this post:

Create a Link

<< Home