Omani biofuel project involves tapping date palms - a closer look

From the futuristic science of synthetic biology, to the ancient art of tapping palm trees... Earlier we referred to a very ambitious biofuel project presented by an entrepreneur from Oman. Mohammed bin Saif al-Harthy and his associates at the Oman Green Energy Company announced they were going to utilize 10 million of the region's ubiquitous date palms as a feedstock for ethanol. Initially it was not clear which parts of the tree would be used, because al-Harty stressed that neither the fruit, nor the cellulosic biomass would be harvested.

From the vague project description we deduced that it might involve the traditional technique of tapping sucrose-rich sap from the palm tree (Phoenix Dactylifera), as is still done today to make date palm wine, sugar and syrup. Reuters' AlertNet service conducted a telephone interview with al-Harty and confirms that this is indeed the case.

Tapping traditions

Tapping trees is very labor intensive and demands traditional skills needed to guarantee the survival of the tree. The technique constitutes a severe intervention, but the rewards may be worth it: sap yields can be high (up to 10 liters per tree per day), the sugar content is high as well and the juice can be readily fermented and distilled (more below).

The date palm sap stores the bulk of its reserve of photosynthetically produced carbohydrates in the form of sucrose in solution in the vascular bundles of its trunk. When the central growing point or upper part of the trunk is incised the palm sap will exude as a fresh clear juice consisting principally of sucrose. When left to stand and favoured by the warm season (when tapping takes place), breakdown of sucrose will soon commence, increasing the invert sugar content, after which fermentation will set in spontaneously by naturally occurring yeasts and within a day most of the sugar will have been converted into alcohol.

Tapping deprives the palm of most of its (productive) leaves and food reserves and to recuperate these losses it is knocked out for at least 3 or 4 years before it will bear a full crop of fruit again. A severe wound inflicted on the palm is kept open every day to maintain the sap flow. The palm's survival depends on the skill of the tapper because if the daily scarring is carried on too far, the palm will die. Literally the palm's life balances on razor's edge:

biofuels :: energy :: sustainability :: date palm :: tapping :: sugar :: ethanol :: Oman ::

biofuels :: energy :: sustainability :: date palm :: tapping :: sugar :: ethanol :: Oman :: Other palms

In some countries, like India, tapping (wild) date palms is an established cottage industry and several other trees have undergone such traditions over the course of centuries - from the African oil palm and the coconut to less well known palms such as Arenga saccharifera, Caryota urens or Borassus flabellifer. Traditions go back thousands of years. Earlier, we reported about the Nypa fruticans or mangrove palm, a tropical species with a long history of being tapped for its sugar rich sap and which recently attracted a major ethanol investment in Malaysia (more here). A good overview of such ancient tapping techniques, the products they yield, and the wide variety of palms with potential can be found in Christophe Dalibard's study, titled "Overall view on the tradition of tapping palm trees and prospects for animal production", to which we referred earlier.

Yields

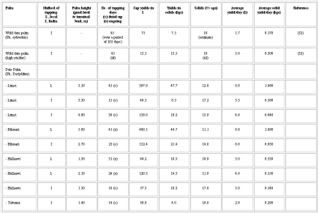

In his book 'Date Palm Products', written for the FAO, W.H. Barreveld devotes a chapter to different tapping techniques used on the date palm. He includes an overview of yields, both from Arabia (for Phoenix Dactylifera) and from India (where the 'wild' date palm, Phoenix Sylvestris, is tapped on a wide scale). The numbers look as follows (click to enlarge):

The sugar contained in the palm juice can be processed into a range of products, from jaggery and crystalline sugar with remaining molasses, to sugar-candy, large sugar crystals and sugar syrup.

Barreveld provides us with a number that allows us to estimate the ethanol potential of a hectare of tapped date palms. As an average the outturn of jaggery is 10-15% of the weight of the raw juice. Jaggery itself contains between 85-90% of total sugar (composed of different types), the rest being moisture, proteine and fat.

Taking a yield of 8 liters of sap per tree, a planting density of between 156 to 204 trees per hectare, and a harvesting period of 45 days per year (continuous tapping), between 56,160 and 73,440 liters of juice can be harvested per hectare per year. From this amount some 5616 to 7344 kilograms of jaggery can be obtained at low conversion efficiencies, which comes down to 4550 to 6240 kilograms of pure sugar (low estimate). As a rule of thumb, conventional yeast fermentation produces around 0.5 kg of ethanol from 1 kg of any the C6 sugars. In short, from one hectare of tapped date palms, some 2275 to 3120 kilos of ethanol can be obtained.

These raw numbers are based on yields observed in villages that practise the ancient tapping techniques. With some research they can probably be increased significantly. Even the relatively simple act of tapping a tree can become a field of biotech research and innovation, as was demonstrated over the course of the past years in the case of rubber tapping, a process that has seen the introduction of novel techniques such as gas stimulation with ethylene, which enhances the flow of sap (more here). Basic R&D in date palm tapping techniques will yield similar innovations.

Labor intensity

Still, technicalities, potential and traditions aside, tapping is labor intensive. This explains the very high number of jobs that the project is expected to deliver (up to 3500 people working on 80,000 trees -, in a second phase, 10 million trees will be tapped). In the field of energy this is rather problematic. The entire purpose of modern energy is to allow man to use up less physical energy from his own body, and to let the energy technology do it for him. If an army of low-paid tappers is needed to harvest fuel for another segment of society, then questions about equity and social sustainability must be asked.

Earlier, we hinted at this problem by comparing the 'jobs delivered per joule of energy' for a series of energy technologies and resources: from oil, gas and coal to renewables such as wind, solar and different biofuels. In the case of biofuels, harvesting some crops is so labor intensive, that they can only function in a social system based on low-skilled, manual and badly paid labor.

Some crops, like palm oil, are harvested manually, but because of their extremely high yields, they allow smallholders and harvesters to make a decent living. For a crop like jatropha, this is not certain. Sugarcane is being mechanised.

Of all possible non-mechanised harvesting techniques - cutting (cane), picking (jatropha seeds), slashing (oil palm fruit bunches) and tapping (palms, rubber trees) - tapping belongs to the more labor intensive ones because it requires quite some precision work.

Conclusion

It is very interesting to see an entrepreneur from a developing nation sharing the enthusiasm for biofuels. Mohammed bin Saif al-Harty wants to export to world markets and turn his oil-producing Sultanate into a biofuel empire.

He has seen an opportunity and if it works out in a socially acceptable way, then all the better, because reviving an ancient art to fuel the future is a beautiful idea. Moreover, if the project succeeds, we could be looking at a vast new expanse of land - stretching from the semi-arid zones and deserts of North Africa over the Middle East and well into Central Asia - where sugar can be tapped for biofuels.

Slide show: all pictures on the traditional date palm tapping technique were taken from 'Date Palm Products', written for the FAO, by W.H. Barreveld.

References:

Reuters: Interview-Omani sees date palms as future fuel - June 28, 2007

Christophe Dalibard, Overall view on the tradition of tapping palm trees and prospects for animal production, International Relations Service, Ministry of Agriculture, Paris, France, Volume 11, Number 1 1999.

W.H. Barreveld, Date Palm Products, FAO Agricultural Services Bulletin N° 101, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, 1993

Biopact: Nipah ethanol project receives major investment, January 05, 2007

--------------

--------------

Siemens Energy & Automation, Inc. and the U.S. National Corn-to-Ethanol Research Center (NCERC) today announced a partnership to speed the growth of alternative fuel technology. The 10-year agreement between the center and Siemens represents transfers of equipment, software and on-site simulation training. The NCERC facilitates the commercialization of new technologies for producing ethanol more effectively and plays a key role in the Bio-Fuels Industry for Workforce Training to assist in the growing need for qualified personnel to operate and manage bio-fuel refineries across the country.

Siemens Energy & Automation, Inc. and the U.S. National Corn-to-Ethanol Research Center (NCERC) today announced a partnership to speed the growth of alternative fuel technology. The 10-year agreement between the center and Siemens represents transfers of equipment, software and on-site simulation training. The NCERC facilitates the commercialization of new technologies for producing ethanol more effectively and plays a key role in the Bio-Fuels Industry for Workforce Training to assist in the growing need for qualified personnel to operate and manage bio-fuel refineries across the country.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Links to this post:

Create a Link

<< Home