Biofuels and the left - who's right: Lula, Prodi, Castro or Chavez?

Brazil's left-wing president Lula da Silva visits with Bush and signs a biofuel cooperation agreement, saying it will help in the fight against global poverty, increase energy security and help mitigate climate change. Fidel Castro lashes out and accuses Bush of promoting global hunger instead. Brazil replies respectfully that Castro 'doesn't really understand a thing about biofuels'. Senior Eurosocialist Romano Prodi for his part goes to Brazil to sign a pact for joint investments in biofuels in Africa, which, he says, will bring jobs, incomes and food security to some of the world's poorest farmers. Venezuela's supreme revolutionary and petroleum exporter Hugo Chavez meanwhile builds 17 ethanol factories at home, and actively supports the construction of another 11 biofuel plants in... Cuba. At the same time he keeps bashing Bush and cautions his collegue Lula against siding with the U.S. on other policy areas. Mexico, which supposedly already experienced first-hand what Castro described - a biofuel-induced food crisis - has meanwhile sided with Brazil and decided to start a biofuels program of its own...

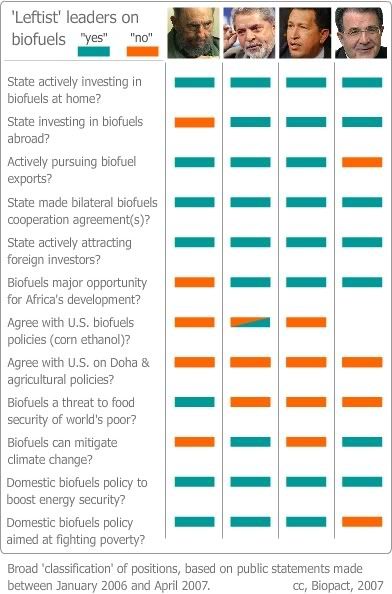

Clearly, biofuels and their potential effects on energy and food security are issues that divide some of the leading left-wing politicians of this world. They have become the kernel of different ideological views on economic development. The complexities of the debate allow for a wide range of positions, which the leaders do not hesitate to express vividly and with the necessary hyperbole. We try to summarise some of these positions in this article, and present a quick overview in the table (but mind you, this is just a rough interpretation and categorisation, based on public statements).

Besides these most outspoken protagonists, virtually all other South American countries ruled by left-wing governments - Chile, Uruguay, Argentina and Ecuador - have launched green fuel policies and production plans of their own, often presented within a social framework aimed at alleviating rural poverty. They proceed rather discreetly though. (Ecuador's socialist president Rafael Correa signs a biofuel cooperation agreement with Brazil as we write this.) Finally, that symbol of the pragmatic global left - the Chinese Communist Party - adds an interesting perspective on bioenergy, which it stressed during its latest party congress: biofuels offer an opportunity to close the dangerously growing income gap between rural China and its wealthy urban citizens; it can slow down rural-urban migration and strengthen the livelihoods of the country's 600 million poor farmers who will be encouraged to become energy producers provided they stop selling grain and food crops to biofuel producers.

Positions taken in the biofuels debate depend on a chosen set of factors, combined and accentuated to form a particular and unique discourse. It is therefor difficult to answer which one of the left-wing politicians is 'right' and who's 'wrong'? What we can do, though, is look at some of the hidden agendas that shadow their publicly expressed points of view.

But in order to do so, we first need to establish a few basic facts about agriculture, trade, biofuels and energy in the developing world:

bioenergy :: biofuels :: energy :: sustainability :: ethanol :: biodiesel :: biomass :: social sustainability :: rural development :: poverty alleviation :: food security :: capitalism :: ideology :: free trade ::

bioenergy :: biofuels :: energy :: sustainability :: ethanol :: biodiesel :: biomass :: social sustainability :: rural development :: poverty alleviation :: food security :: capitalism :: ideology :: free trade :: 1. the world produces a vast amount of agricultural products, more than enough to feed all people on this planet one and a half times. Still, given this enormous abundance, around 800 million people are chronically under-nourished today. On the other hand, according to the International Association of Agricultural Economists there are more overweight and clinically obese people today than under-nourished people. Obesity is becoming the norm globally and under-nutrition, while still important in several countries and in targeted populations in many others, is no longer the dominant disease. It is important however to ask why countries with a very large agricultural potential suffer chronic food deficits.

2. about half of the more than 80 countries facing periodic or chronic food deficits - the bulk of which can be found in Sub-Saharan Africa - have more than enough suitable agricultural land and the right agro-ecological conditions to feed their own populations several times over. With optimal inputs, countries like Mozambique, the Central African Republic, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Angola or the Democratic Republic of Congo - all 'food insecure' - should be world leading food exporters.

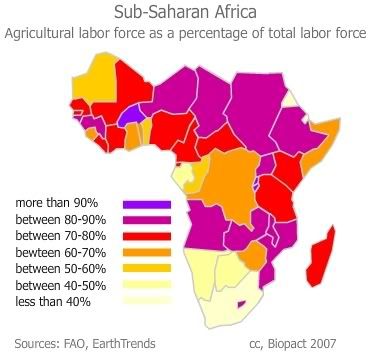

3. more than 60% of sub-Saharan Africa's population is employed in the agricultural sector. In many countries the percentage of the labor force making a living off the land exceeds 70%:

4. there is a consensus amongst development economists about the main macro-economic reasons for food-insecurity in the developing world. These factors are (randomly ranked): (1) lack of investments in agriculture (sub-Saharan Africa's productivity is 30% of what it should be if standard agricultural techniques, knowledge and skills were utilised), (2) lack of investments infrastructure (primary, secondary and tertiary roads, railroads, ports, harbors - obviously, without these infrastructures, there is no way to bring food to market or to export it and create income) and a lack of access to markets, (3) distorted markets (subsidies, tariffs, non-trade barriers - the Doha Development Round has stalled over this, because the US and the EU are not willing to lift their subsidies); this has turned many developing countries into net food-importers, whereas, from a purely agronomic point of view, they should be food exporters, (4) policy and political factors: political instability, bad governance, corruption, weak institutions and a bad investment climate in general, and (5) energy dependence levels and a lack of access to energy.

5. there is a strict correlation between virtually all the factors determining 'Human Development' (as defined by the UN), and access to low-priced fuels and energy. The lower the access to energy, the lower the availability of basic social services (education, health), the lower access to clean drinking water, the higher food insecurity. In short: fuel and energy are absolutely critical for a nation to develop. Without general access to affordable fuels and energy there is no human development and generalised poverty. (We will be exploring the very clear correlation between the HDI and the EDI - the Energy Development Index - in another piece soon; but see Chapter 9 of the IEA's World Energy Outlook 2004, which is entirely devoted to 'Energy and Development' [*.pdf] and which remains one of the most complete analyses on the importance of energy to development).

6. the economies of oil-importing countries with a high 'energy intensity' - the bulk of which can be found in the developing world - suffer greatly under rising fossil fuel prices; the impact is direct and can be felt in all socio-economic sectors, from agriculture and trade to basic social services provided by the state. In every country studied, the IEA found that a combination of capital, labour and energy contributed more to economic growth than did productivity increases; increased fuel prices directly reduce economic growth, in a very straightforward way. So on this front too, there is a strict correlation: the higher the energy intensity of an economy and its oil import burden, the higher the effect of rising energy prices on fundamental macro-economic factors (such as lower GDP growth, increased inflation, debt burden and deficits). Finally, and most obviously, funds that are spent on imported oil cannot be spent on social development, poverty alleviation or indeed on initiatives aimed at strengthening the food security of people [see the IEA report referred to in point 6].

7. biofuels produced in an explicitly sustainable manner in the tropics and the subtropics - such as ethanol from sorghum, sweet potatoes, sugarcane or cassava - are competitive with petroleum today. Brazilian sugarcane-based ethanol costs between US$35 to US$40 per barrel of oil equivalent energy. In other words, for every barrel of biofuels produced, a developing country's economy can mitigate the disastrous socio-economic effects of high fossil fuel prices considerably.

8. biofuels can be produced in an environmentally sound manner; researchers from the a-political International Energy Agency have determined that sugarcane-based ethanol production in Brazil, as it exists today, is 'largely sustainable'.

9. the IEA's Bioenergy Task 40 - an a-political research group uniting some of the leading researchers in (bio)energy - has determined that from a purely technical perspective, around 750 Exajoules of energy can be produced from biofuels the feedstocks of which are grown in the developing world; and this in an explicitly sustainable manner, that is, without destroying any tropical rainforest or established biodiversity hotspots and without threatening the food security of (rapidly) growing populations (earlier post). In short, the technical potential is there; the way this potential is exploited is another matter.

10. another IEA Bioenergy study shows that if the most stringent and complete set of social and environmental sustainability criteria were adopted for biofuels, production costs would only increase marginally (or alternatively the potential would decrease only slightly) - we reviewed this research elsewhere.

Complexity allows different points of view

These are neutral, objective facts. The reader can think of ways to combine them and make up his mind about the challenges, risks, potential advantages and disadvantages associated with biofuels within this context.

Obviously, there are also facts that are not essential to the production of biofuels per se, but that do say a lot about our current economic system and the pressures it exerts on the environment and on the social relations between the poor and the wealthy. Facts like: the destruction of rainforests for palm plantations in South-East Asia, or the fact that sugarcane cutters in Brazil only receive minimum wages and are faced with the grim choice of doing hard, temporary work on a plantation or ending up in even greater poverty in the favelas of the mega-cities. There is also the fact of Brazil's Social Fuel policy, which tackles the problem of a lack of social sustainability in a way that seems to work quite well...

With these basics in mind, biofuels can obviously go many different ways. They can be produced in a sustainable or in a totally unsustainable but highly profitable manner; they can benefit millions of farmers when they are allowed to become energy farmers, or push them out of the market; they can benefit the world's poor (because access to mobility and energy is crucial for development); they can mitigate climate change like no other technology (e.g. in carbon negative energy systems), or they can add to the problem (e.g. when carbon sinks such as rainforests are logged or peatlands damaged to make way for biofuel crops); they can push back environmental degradation and save biodiversity, or destroy it; they can make the poorest economies independent of the high oil prices that devastate them so much...

This complexity and the diversity of possible outcomes is responsible for the confusion about the potential benefits and disadvantages of biofuels and for the way the left-wing politicians mentioned earlier position themselves. Depending on which factors they highlight, they can bring a largely positive story about the opportunities brought by biofuels, or they can paint a dark, threatening situation.

The following is an overview of the different actor's positions. We limit ourselves to describing the views of the four protagonists presented in the table.

Brazil

The Brazilian government, and president Lula in particular, stress the opportunity biofuels bring to (1) stimulate energy independence, (2) fight climate change, (3) alleviate poverty, especially in developing countries with large rural populations and high oil import bills, (4) protect biodiversity and ecosystem survival on a massive scale (the use of efficient and sustainable biofuels is one of the most effective strategies of rapidly reducing climate change, as it can be implemented on a large scale, both in the power generation and transport sectors, without too much added costs and while still allowing economic growth; pragmatically speaking, not using biofuels results in more greenhouse gas emissions, with potentially disastrous effects on biodiversity and the global environment).

In order to achieve the rapid spread of biofuels across the world and to create a truly global market, cooperation with large consumers and producers (such as the US and the EU) is needed. Brazil intends to lead a revolution in the Global South, by providing developing countries access to its expertise, knowledge and technologies. To this aim, Brazil recently created an Africa office, led by the country's main agricultural research organisation, Embrapa.

Brazil stresses that there is no shortage of land, neither in Brazil itself nor in the developing countries it aims to partner with. It estimates that in Brazil alone, a total of 330 million hectares suitable for energy crops are available, of which some 150 million hectares are former pastures that need reconversion. The country currently utilises less than 6 million hectares of land for the production of ethanol. Sugarcane does not grow in rainforest soils.

Venezuela

The government of Venezuela takes an ambiguous approach towards biofuels. On the one hand the fifth largest oil exporting country is seriously investing in biofuels itself and recently announced it would be building 17 ethanol plants and establish energy plantations across the country, as a way to provide employment to the rural poor. The country also signed a biofuels cooperation pact with Cuba aimed at strengthening energy independence and self-reliance. The deal focuses on the construction of 11 ethanol plants that will make use of Cuba's revived sugarcane industry.

Last year, during a visit to Malaysia, president Hugo Chavez invited Malaysian palm oil companies looking for land to come to Venezuela to establish plantations. He said his country has a large amount of 'excess' land suitable for palm oil, and that it is available to his Asian 'friends' in case they cannot expand in their own country.

Analysts think Chavez's constantly changing position on biofuels, and his criticism of Lula's agreement with the US, can be explained in part by his fear that the US has found a way to negate his attempts to become the dominant political force in South America. The alliance with Brazil effectively weakens Chavez's position and reduces the effectiveness of his use of Venezuela's oil resources as a political weapon. On the other hand, the amount of petroleum that can be replaced by biofuels in the immediate future is marginal, so Chavez doesn't really have to fear losing his grip on his partial control of America's oil supplies. For this reason, the American argument that the green alliance with Brazil side-steps Chavez's influence remains largely symbolical.

Italy

Italian Prime Minister Romano Prodi recently visited Brazil and announced a cooperation agreement to stimulate biofuel expansion in Africa. Two countries were named as first candidates: Angola and Mozambique, which both have a very large sustainable biofuels potential. The motivation is largely similar to that of the Brazilian government's initiatives in Africa: biofuels offer an opportunity to revive, modernise and strengthen the agricultural sector, which employs most of the country's people (the percentage of Mozambique's and Angola's labor force making a living off the land is 81% and 85% respectively). Both countries are still recovering from civil conflict, that ruined their once thriving agricultural sector and the infrastructures that allowed the distribution of agricultural products. From this strengthened agriculture comes rural development, increased food security, access to energy and a new development paradigm. That is the idea. Direct foreign investments provide the capital, Brazilian biofuels expertise the knowledge and the technologies.

Prodi publicly stated that Italy can never free enough arable land to satisfy its own growing thirst for biofuels. Thus its proposition for Africa is at least in part purely opportunistic: to import cheap biofuels from the South, in order to meet the EU's targets in an easy way.

Moreover, the agent who will actively implement Italy's initiative in Africa is ENI, the oil company in which the Italian state holds the majority. ENI is Italy's largest industrial company, but it has been experiencing great problems with its petroleum production activities in Nigeria. For this reason it is exploring new markets in Africa, the last petroleum frontier. Biofuels and the arguments used by ENI to promote them, might be nothing more than window-dressing, even though the oil company has forged its Africa-centered alliance with Petrobras, Brazil's state-run oil company.

Of Petrobras one can be relatively sure that it is serious about promoting biofuels for the sake of biofuels. After all, Petrobras is the company that made Brazil's green revolution happen; it is also actively engaged in promoting Brazil's Social Fuel policy, which ensures biofuels are produced in a socially sustainable way and help lift the rural poor out of poverty.

Cuba

In two columns, President Fidel Castro has lashed out at President Bush and the ethanol agreement with Brazil. He accuses the American president (but not his Brazilian counterpart) of promoting hunger on a global scale. Brazil has meanwhile responded, saying that Castro's criticisms are very old, have been debunked long ago, and show a deep lack of understanding of what biofuels are about.

Castro's position and the use of the hunger-metaphor must be read as an attack against an economic paradigm that, indeed, has led to a concentration of power and capital, particularly in the agricultural sector. He fears that this model might be replicated in the area of biofuels. In this he does have a point: large multinationals have succeeded in dominating the ethanol industry in Brazil and have pushed small farmers off the land.

But his hyperbole that biofuels automatically lead to increased food shortages is a myth that has no basis in development economics. Biofuels allow a particular group of countries - like Cuba - to mitigate some of the devastating effects of increased energy prices. High oil prices impact food production, trade and the economy at large. Fidel Castro knows this better than anyone else, given his experience with the chronic and dramatic fuel shortages that came with the collapse of the Soviet Union, which supplied Cuba with all the oil it needed. This episode brought Cuba's economy to a standstill; shrinking energy supplies were the single biggest factor causing this disaster.

This last point is important, because it has pushed Fidel Castro himself to promote biofuels in Cuba - and not in a particularly marginal way. The island state used to be a major sugar producer, but again, with the USSR gone, the agricultural sector and Cuba's sugar exports collapsed. Today, the Cuban government is extatic about the opportunities biofuels offer to revive the sector and help solve its energy insecurity problem at the same time.

As said earlier, Cuba signed a biofuel cooperation agreement with Venezuela, that will result in the construction of not less than 11 ethanol plants. No doubt, Cuba's biofuels are more innocent that those made in other countries...

Castro has to play his role as symbolic whip. The dictator embodies a critical discourse on globalisation that is legitimate and welcome as it cautions against the dangers inherent in uncontrolled capitalism. Biofuels and the way they are produced are not immune to this danger. But they are not automatically or necessarily the code-word of the laissez-faire capitalism that fuels inequality across the globe. The can fit perfectly into a left-wing paradigm about energy and development. Brazil is making the point.

To conclude this brief panorama of the way the left-wing is divided over biofuels, we wish to present the following, simplified illustration of how bioenergy can be the sign of a new era in which more equality, less poverty, energy access for all and sustainable development go hand in hand. Since we are walking in the minefield of ideology anyways, the reader will forgive us the binary, antagonistic and mildly propagandistic representation:

The Biopact team - explicitly built around the idea that promoting biofuels can open a bright green and somewhat reddish world in the Global South.

--------------

--------------

The Michigan Economic Development Corporation last week awarded a $3.4 million grant to redevelop the former Pfizer research facility in Holland into a bioeconomy research and commercialization center. Michigan State University will use the facility to develop technologies that derive alternative energy from agri-based renewable resources.

The Michigan Economic Development Corporation last week awarded a $3.4 million grant to redevelop the former Pfizer research facility in Holland into a bioeconomy research and commercialization center. Michigan State University will use the facility to develop technologies that derive alternative energy from agri-based renewable resources.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Links to this post:

Create a Link

<< Home