An in-depth look at Brazil's "Social Fuel Seal"

Even though the Brazilian biofuels revolution has been a scientific, agronomic and technological success, it has not been a very equitable one. Professor Ignacy Sachs, economist at the EHESS, green geopolitical thinker, éminence grise of development economics, and expert [*.pdf] on the social effects of Brazil's ethanol industry, is formal: the sector has strengthened an age-old tradition with roots going back to the colonial era, in which the increasing concentration of capital, land and power, and the commodification of rural labor go hand in hand. Segments of Brazil's civil society share Sachs' vision on the ethanol industry (amongst them Brazil's socially engaged Catholic Church) and are calling for stronger interventions by the left-leaning Lula government.

Even though the Brazilian biofuels revolution has been a scientific, agronomic and technological success, it has not been a very equitable one. Professor Ignacy Sachs, economist at the EHESS, green geopolitical thinker, éminence grise of development economics, and expert [*.pdf] on the social effects of Brazil's ethanol industry, is formal: the sector has strengthened an age-old tradition with roots going back to the colonial era, in which the increasing concentration of capital, land and power, and the commodification of rural labor go hand in hand. Segments of Brazil's civil society share Sachs' vision on the ethanol industry (amongst them Brazil's socially engaged Catholic Church) and are calling for stronger interventions by the left-leaning Lula government.Sugarcane ethanol as it is currently produced may well be environmentally sustainable and highly efficient (earlier post), doubts clearly remain over its equally important social sustainability (earlier post): labor conditions for sugarcane cutters and planters are poor (even though new laws on safety are changing this situation), wage levels are basic (but here too, new minimum wages have seriously improved the fate of the workers) and the industry stimulates seasonal labor and internal migrations. On the other hand, increased mechanisation - 1 in 3 plantations are now harvested mechanically - takes away the chance for many rural poor to make a living alltogether, and transforms them from rural into urban migrants who join the millions of poor living in the favelas of Brazil's mega-cities.

The left-leaning Brazilian government is now trying to create a rupture in this complex situation by implementing unique legislation that offers the opportunity to make biofuels the motor of a process in which the redistribution of wealth and the fight against rural poverty are key, and which provides secure livelihoods to poor farmers. The goal is to create a win-win synergy between industrial biofuel producers' needs to be competitive and small family-run farms whose livelihoods are otherwise threatened. Mind you, the policy is new and concrete results still have to prove its viability. But at first sight, the compromise looks promising.

'Social fuel'

The core of the new policy is the so-called 'Social Fuel Seal' - an instrument that gives biodiesel producers incentives to source their raw materials from smallholders and family farmers. The farmers in turn receive technical assistance and agricultural training, organised by an extension service financed by the biofuel producer that goes beyond mere feedstock production and that enhances food production and security. Under the Social Fuel Seal both biodiesel producers and family farmers can tap into special credit lines, whereas small farmers enjoy a strong body of social rights that empower them during contract and price negotiations. They are assisted and stimulated to create 'Family Farmer Cooperatives' that act as the intermediary between the smallholders and the biodiesel producers. In fact, the system itself contains a mechanism that makes biodiesel producer prefer to work with such cooperatives.

The Social Fuel Seal is tied to Brazil's new National Biodiesel Program, and was crafted precisely to break with the problems inherent in the older Bioethanol Program. The Seal is quite refined and directly intervenes in the most crucial aspect of biodiesel production: feedstock costs and modes of production. The system takes into account regionally determined social inequalities and the geographically specific agro-ecological potential for biodiesel feedstock production. It can become a model for other developing countries aiming to launch biofuel programs.

What follows is an in-depth look into this social policy, based on the original legislation. The Biopact team translated the most significant texts in its series of Biofuel Policy Documents, which can be downloaded for free (see below).

Incentives: tax breaks

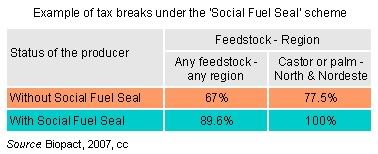

The idea behind the Social Fuel Seal is simple: biodiesel producers receive tax breaks if they source feedstocks produced by small farmers. The progressive tax breaks are determined by (1) the kind of farmer the producer sources from, (2) by the region in which the farmers produce their oil-rich crops, (3) by the specific crop (this distinction is made because investments in particular crops - like castor or jatropha which grow well in semi-arid zones - logically imply investments in particular regions associated with these agro-ecological conditions; the same regions are correlated with social inequality levels) and (4) by the share of feedstocks sourced from the particular categories of farmers as a percentage of the total amount of raw materials used by the biodiesel producer.

Depending on the combination of these categories, the tax breaks are progressive and can be represented in the following matrix (which is just one example):

biomass :: bioenergy :: biofuels :: energy :: sustainability :: biodiesel :: social sustainability ::poverty alleviation :: rural development :: cooperative ::Brazil ::

biomass :: bioenergy :: biofuels :: energy :: sustainability :: biodiesel :: social sustainability ::poverty alleviation :: rural development :: cooperative ::Brazil :: - The federal social security contribution, levied on the gross revenue of the biodiesel company ("Cofins"), which is fixed at 7.6%.

- The federal social inclusion contribution, part of a Social Integration Program ("PIS/PASEP"), equally levied on the company's gross revenue, fixed at 1.65%.

In practise, and as things stand today, this comes down to the following numbers per cubic meter of biodiesel: a producer without the Social Fuel Seal, who doesn't source from either kind of regionally categorised small farmers, pays R$39.65 PIS/PASEP and R$182.55 COFINS (or US$19.2 and US$88.4, or a total of around US$110 per ton). If he sources from the best category, he saves US$ 110 per ton - which is a highly attractive proposition.

Several major biodiesel producers in Brazil have joined the program. Testimony to the fact that the Social Fuel Seal's regionally and socially determined tax break scheme is quite refined, can be found in a map which shows the regional distribution of biodiesel producers who joined the program in 2006 (click to enlarge).

Several major biodiesel producers in Brazil have joined the program. Testimony to the fact that the Social Fuel Seal's regionally and socially determined tax break scheme is quite refined, can be found in a map which shows the regional distribution of biodiesel producers who joined the program in 2006 (click to enlarge).Obtaining the Social Fuel Seal

But there are costs involved for the biodiesel producer - he will have to weigh them off against the benefits of the tax break. If a biodiesel producer wants to obtain the Social Fuel Seal, he must adhere to the following strict criteria:

- he must enter into formal contracts with the feedstock producers and follow a strict contract negotiation procedure

- he must allow the presence of a rural union representative during all negotiations; this representative can be delegated by the Family Farmers Cooperative, or, in case the producer sources from individual farmers, by a government-recognised rural union appointed for this task (note that the biodiesel producer will prefer to negotiate with Cooperatives, in order to cut back on red tape and cumbersome contract negotiations with individual producers; this system stimulates the creation of Family Farmer Cooperatives)

- he must provide clearly described extension services, technical assistance and agricultural training aimed at helping the farmer increase production, not only of biofuel feedstocks, but of an integrated fuel-and-food production system; he can organise this himself, but in that case an easy but strict procedure must be followed that guarantees high quality services to the family farmers; alternatively, he can outsource these tasks to trustworthy (and certified) institutions.

- his must allow a yearly evaluation of the project by external agencies, managed by the Ministry of Rural Development

The Social Fuel Seal further breaks down the amount of feedstock the producer must minimally source from small farmers, relative to the geographical zone he operates in and sources from. The zones are refined and correlate strongly with socio-economic indicators (such as income inequality, poverty, educational and health status, etc...). Three broad regions are identified (and further refined by the PRONAF - see below). The quantities involved can be expressed both as a percentage of the value of the crops, or in absolute numbers, as a metric quantity (tons). The methods depend on which crops are involved and the combination of feedstocks the biodiesel manufacturer wishes to use.

- The semi-arid North and the Nordeste - this is by far Brazil's poorest region and has been the subject of many attempts to create policies that effectively fight poverty here; if the producer wants to obtain the Social Fuel Seal and the best tax breaks, he must source 50% of his biodiesel feedstocks from (small farmers) from this zone

- The South-East and South: fertile but relatively poor regions; if the producer wants to obtain the Social Fuel Seal and the best tax breaks, he must source 30% of his biodiesel feedstocks from (small farmers) from this zone

- The North and Center-West region - Brazil's most fertile regions for the biodiesel crops covered by the legislation; if the producer wants to obtain the Social Fuel Seal and the best tax breaks, he must source 10% of his biodiesel feedstocks from (small farmers) from this zone

All feedstock sales and acquisitions are carefully registered by both parties, biodiesel producer and small farmer.

The producer's project is evaluated on a yearly basis but is normally granted the Social Fuel Seal for a period of five years. A simple concession, evaluation, renewal and cancellation procedure has been created. Additionally, he must inform the agricultural cadaster of his activities (related to land use and raw material sourcing), which installs a certain level of transparency.

Who are the small farmers?

The farmers who are the subject of the policy are clearly defined: they are registered within a framework called "Programa Nacional de Fortalecimento da Agricultura Familiar" - "National Program to Strengthen Family-run Agriculture" (PRONAF), managed by the Ministry of Rural development. A well organised data-stream identifies each farmer, the contracts he entered into, his social position and his training needs.

A clear profile of each farmer is thus available, which allows the administration to classify him according to a particular category. This category is then used to calculate the tax breaks for the biodiesel producer.

The farmers are assisted and stimulated into joining their forces by creating Family Farmer Cooperatives. It is reasonable to assume that the biodiesel producer prefers to negotiate with such a Cooperative: what he pays in terms of losing a bit of his negotiation power, he wins in cutting red tape and in time lost by contracting with individual farmers.

The farmers in question are typically smallholders who own between 1 and 4 hectares of land, often just enough to support themselves. With training and better inputs - foreseen under the program - they improve their food security while producing biofuel feedstocks on the side. What is more, they are stimulated to acquire more land, given the fact that they enjoy minimum prices and well defined, advantageous supply contracts, which strengthens their capacity to plan over a longer term, make better informed decisions on what to grow, and ultimately to invest savings into more land.

There are examples of biodiesel producers using the Social Fuel Seal, who have actively negotiated better land deals for the small farmers they contract.

Farmers from Brazil's poorest, semi-arid region, the Nordeste, are the main beneficiaries of the program. It is here that biodiesel crops like jatropha and castor thrive well and require relatively low inputs. Importantly, these crops are highly suitable for small, integrated systems that strengthen food production. Since they are perennial crops, they can act as shades for legumes. Clear scientific evidence has established that win-win synergies appear when intercropping schemes are used (to go short and to stick with just this example: the perennial crops in question produce and enhance fungi growth, which is beneficial for legume cultivation, whereas legumes fix nitrogen which stimulates the growth of the perennial shrubs).

The biodiesel producer's extension service focuses on such integrated systems. The different crops and their implied potential for integration in food-and-fuel systems, is clearly described in the legislation. It is one more - albeit implicit - criterion used to determine the level of the tax break.

Credit lines

Both the small farmers and the biodiesel producer can tap special credit lines and low interest loans from designated banks and financial agents. For the small farmer, a system of micro-credits was created for the production of oil-rich crops (the lines are crop-specific) within the framework of the PRONAF. This institution already offers credits to assist small farmers in their normal agricultural activities; the new credit-line does not compete with the existing one.

PRONAF is integrated in a broader set of highly effective social programs aimed at reducing rural poverty (see below).

Advantages of the system

Besides the attractive tax-breaks, the Social Fuel Seal can be used by the biodiesel producer as a marketing instrument. Even though there are no studies yet on the appeal of the 'brand' and the concept, it is reasonable to assume that it offers a great marketing advantage.

We do have some references in this regard: studies on the value of sustainably produced palm oil, in which 'sustainable' was explicitly illustrated with references to small integrated food-and-fuel systems used by typical smallholders, show that the concept has a considerable marketing strength. Experts predict that as biofuels from the tropics and the developing world become more important, the commercial value of such a label will increase likewise. This provisional evidence was produced by the Roundtable for Sustainable Palm Oil - an ongoing dialogue between civil society and industry - and its smallholder taskforce. See this study - Towards better practice in smallholder palm oil production - [*.pdf] and more specifically the chapter on smallholders and biofuels.

For the farmers, the advantages of the Social Fuel Seal are obvious as well:

- they receive clearly negotiated supply contracts, with a clearly indicated time-frame and prices

- their contracts are negotiated collectively (via the Cooperative) and in the presence of experienced social actors (a rural union representative)

- they enjoy mandatory extension services and training;

- they can rely on the protection of a sophisticated registration, monitoring and evaluation system;

Finally, the system strengthens the creation of cooperatives, and consequently offers the advantages inherent in this organisation form: a democratic decision making process, low entrance and membership barriers and stronger positions during negotiations.

In short, at first sight, the Social Fuel Seal has found an interesting and fine balance between on the one hand the many criteria that need to be fulfilled in order to be able to speak of biofuels that are genuinely 'socially sustainable', and on the other hand, the need for biodiesel producers to remain competitive.

Professor Sachs, with who we opened this article and who inspired the Lula government, has given careful thumbs up for this program. As a leading figure in the analysis of the relationships between the world food and energy system, and of the social effects of rapid agro-industrial expansion in the Global South, his fiat is important (some of Sach's publications are classics in development economics; they include Brazilian Perspectives of Sustainable Development of the Amazon Region, Global Ecology: Transition Strategies for the Twenty-first Century, and Food and Energy: Strategies for Sustainable Development.)

In Sach's mildly philosophical view, biofuel production, like agriculture, is centered around resources and modes of production that are so primordial to man that they embed a kind of 'social memory', not only of capitalism and colonialism but of pre-capitalist and pre-colonial modes of production. Collective land tenure, nature, farming and social and territorial 'rootedness' form the core of this archetypal order of things. Man's relationship with these material conditions is 'primordial' in the sense that if a 'disaster' ever were to strike a society, a community's resilience and survival depends on these conditions.

Sachs thinks that, precisely for this reason, the biofuels future may open the doors to a radically alternative development paradigm, - pointing to explicitly post-capitalist and post-colonialist modes of production - in which cooperation between social actors, forms of communal land ownership, a redistribution of wealth and sustainability are central. Such a paradigm leads to more social equality and the de-commodification of (rural) labor.

The question obviously is: is the 'Social Fuel Seal' really a first, small step towards such a future? And will such a mechanism ever be strong enough to counter a purely economic, market-driven logic of production and accumulation? It remains an open question.

To complement this brief analysis of the Social Fuel policy, we quickly want to look at existing efforts to fight poverty in Brazil, and especially in the regions where it is traditionally and explicitly prevalent - the Nordeste - and for different classes of people - in this case, small, family operated farms and their poor owners. These efforts are tightly linked to the social biofuels program.

The broader context: Brazil's poverty alleviation programs

The Brazilian government has created several socio-economic programs aimed at re-anchoring small farmers in their environment and at reintegrating poor populations into the formal economic fabric of the country. These programs, such as the “Bolsa Familia” (Family Allowance) and the “Salario Familia” (Family Wage) are much more effective tools to fight poverty and reduce income inequality than classic recipees such as raising the minimum wage, according to a recent study by the Institute of Applied Economic Research (IPEA). It is interesting to quickly look at these programs, because they are the building blocks for Brazil's 'Social Fuel Seal'.

When it comes to fighting extreme poverty, the Family Allowance program is seven times more efficient than increasing the minimum wage, points out Paulo Mansur Levy, Director of Macroeconomic Studies at IPEA and coauthor of “An Agenda for Economic Growth and Poverty Reduction in Brazil.” In other words, the Family Allowance program has a similar impact on extreme poverty as an increase in the minimum wage, but uses 85 percent less resources. Levy added that the program’s impact on moderate poverty is 2.5 times more efficient than wage increases.

In terms of income inequality, the Family Allowance cash transfer program is 5 times more effective than a minimum wage increase. Likewise, the Family Wage is also clearly superior to minimum wage increases in all these scenarios, though its impact is smaller than that of the Family Allowance program, Levy said.

The limited effectiveness of using minimum wage increases as a social policy is not all that surprising, according to Levy, given that minimum wage increases apply to everyone; they are not focused specifically on target populations. The fact is that less than 15 percent of poor families have at least one family member working at the minimum wage rate.

Another reason that minimum wage increases do not reach many people living in poverty is that less than 10 percent of workers with incomes close to the minimum wage rate live in extremely poor families, and only 22 percent of workers earning the minimum wage are heads of poor households, according to the study.

Social policies are more effective at fighting poverty due to integration with other policies and their specific focus, Levy said, referring to both programs, which take into account individual income and the number of children in the household.

To eradicate poverty, poor families must become capable of meeting their basic needs autonomously, Levy said. Social programs such as the Family Allowance and Family Wage programs create conditions that allow poor families to take advantage of opportunities to improve their skills and to make the most of them.

Although many families living in poverty probably could not cover their basic needs without the help of these social programs, the support is not intended to be permanent. Rather, it provides an incentive to get out of poverty and helps them learn how to support their families on their own.

Conclusion

The social sustainability of biodiesel production has become the object of legislation and of concrete projects in Brazil. The policy draws on insights obtained from other poverty alleviation programs.

Whereas the by now widely known ProAlcool program symbolises the past, with its vast industrially run monocultures and its armies of impoverished sugarcane cutters, the new Biodiesel Program symbolises a new era: one of small-scale agriculture and cooperatively run production units, tightly linked to improving the material conditions of the country's poorest.

Ultimately, a convergence between the two modes of production might emerge in the future and result in an ideal order of things that takes into account all conflicting factors that drive large-scale biofuel production.

The land area that is currently up for the social experiments is around 1.5 million hectares and will supply a mandated mixture of 2% biodiesel to the Brazilian market. This pales in comparison with the ethanol program and expansion.

Besides state-run oil company Petrobras, several private companies are already participating in the Social Fuel Seal system. Amongst them the Companhia Refinadora da Amazônia, Brasil Ecodiesel, Soyminas Biodiesel Derivados e Vegetais Ltda, who, together, are cooperating with more than 20,000 rural families registered in the scheme, many of whom are united in 'Family Farmers Cooperatives'.

It is too early to assess the merits of this recently developed system. We do however think it represents an elegant balance between the many conflicting factors at play in producing biofuels in the tropics. Brazil's deep-running social inequalities and contemporary conflicts stemming from its complex history which traditionally opposed large landowners and small farmers, will not be solved by the Social Fuel scheme. But it might offer a first step. If concrete results show the system's effectiveness, Brazil has one more field of expertise to share with developing countries in a South-South relationship.

Jonas Van Den Berg & Laurens Rademakers, CC

More information

The Biopact Team has been collecting a set of some of the most interesting policy documents and legislative texts dealing with biofuel production in the developing world. Brazil's experiences and experiments are of particular interest, because of the country's long-running and large-scale programs.

For this article, we drew on three documents that outline the Social Fuel Seal policy. Translations of the official texts can be freely downloaded. They are:

-Decreto N° 5.297, de 6 de Dezembro de 2004: Dispõe sobre os coeficientes de redução das alíquotas da Contribuição para o PIS/PASEP e da COFINS incidentes na produção e na comercialização de biodiesel, sobre os termos e as condições para a utilização das alíquotas diferenciadas, e dá outras providências [*.pdf], English translation [*.pdf]

-Ministério do Desenvolvimento Agrário: Instrução Normativa no. 01, de 05 de Julho de 2005: Dispõe sobre os critérios e procedimentos relativos à concessão de uso do selo combustível social [*.pdf], English translation [*.pdf]

-Ministério do Desenvolvimento Agrário: Instrução Normativa no. 02, de 30 de Setembro de 2005: Dispõe sobre os critérios e procedimentos relativos ao enquadramento de projetos de produção de biodiesel ao selo combustível social [*.pdf], English translation [*.pdf]

Note: these are working translations.

Ignacy Sachs, "Biofuels are coming of age", [*.pdf] Keynote address at the International Seminar "Assessing the Biofuels Option", IEA Headquarters, Paris, IEA / UN Foundation / Brazilian Government, June 20, 2005

Miguel Clüssener-God and Ignacy Sachs, Brazilian Perspectives of Sustainable Development of the Amazon Region, Man and the Biosphere Series.

Brazil's official website on the Programa Nacional de Produção e Uso de Biodiesel.

A handy leaflet outlining the biodiesel program, in English [*.pdf].

Basic overview of the Selo Combustível Social scheme [*Portuguese].

Website of the PRONAF - "Programa Nacional de Fortalecimento da Agricultura Familiar" - (National Program to Strengthen Family-run Agriculture), with which the small farmers are registered and which manages part of the scheme and its dedicated credit lines; the PRONAF's biodiesel section.

The second part of the documentary "Biocarburants: la révolution brésilienne"/"Sprit aus Zucker", which we discussed earlier, is entirely devoted to the Social Fuel Seal. It shows a 'Family Farmers Cooperative' at work in the arid Nordeste, cultivating Jatropha as a biodiesel feedstock, in an intercropping system with legumes.

--------------

--------------

One of India's largest sugar companies, the Birla group will invest 8 billion rupees (US$187 million) to expand sugar and biofuel ethanol output and produce renewable electricity from bagasse, to generate more revenue streams from its sugar business.

One of India's largest sugar companies, the Birla group will invest 8 billion rupees (US$187 million) to expand sugar and biofuel ethanol output and produce renewable electricity from bagasse, to generate more revenue streams from its sugar business.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Links to this post:

Create a Link

<< Home