A closer look at sustainability criteria for biofuels

Global interest in biofuels and bioenergy has increased rapidly over the past few years. It would be no exaggeration to speak of a real biofuel boom: large investments into the sector are being announced on an almost daily basis. There are many factors leading to this green fuel fever - from high energy prices and doubts about the long term security of supplies, to the latest insights into the potentially devastating effects of climate change and the need for low carbon energy.

Global interest in biofuels and bioenergy has increased rapidly over the past few years. It would be no exaggeration to speak of a real biofuel boom: large investments into the sector are being announced on an almost daily basis. There are many factors leading to this green fuel fever - from high energy prices and doubts about the long term security of supplies, to the latest insights into the potentially devastating effects of climate change and the need for low carbon energy.To many, these developments are going too quickly and they rightly caution against the potential dangers of a mass-adoption of biofuels. Environmental and social sustainability criteria should be put in place first, before a global trade in biofuels is allowed to emerge. But the creation and the controlled implementation of such a set of criteria is a slow process, whereas investors and their money move very fast... The nascent biofuels sector makes the conflict between narrow-minded, short-term economic interests and environmental sustainability very apparent.

Sadly, this somewhat simplistic dichotomy ('environment versus profit') has permeated the mainstream media. One type of media tends to focus on the mere commercial aspects of biofuels (announcing investment after investment), whereas another type dismisses all biofuels as an outright disaster without seeing the potential benefits for people, planet and profit. A more nuanced, scientifically sound perspective on the matter is very rare and urgently needed.

We try to offer such a view - hoping others will do so as well -, by presenting an in-depth look at some of the work being done by researchers into the rather complex matter of 'sustainability' as it relates to bioenergy and biofuels. We focus in on the analysis made by scientists from the Copernicus Institute for Sustainable Development and Innovation, at the Utrecht University's, Department of Science, Technology and Society.

Edward Smeets, André Faaij and Iris Lewandowski wrote "The impact of sustainability criteria on the costs and potentials of bioenergy production" for the International Energy Agency's Bioenergy Task 40, which analyses the potential for a global bioenergy trade.

Large potential

In the report, the authors begin by reminding us that many studies have been carried out that quantify the potential of the world to produce bioenergy. Results indicate that various world regions are in theory capable of producing significant amounts of bioenergy crops without endangering food supply or further deforestation. We earlier referred to some of this research (previous post).

The theoretical potential is huge: by 2050, the developing world can produce more than 800 Exajoules of exportable bioenergy, sustainably, whereas the global potential is around 1400Ej per year. Consider that today, the entire world uses around 420Ej worth of energy annually, from all sources (coal, oil, gas, nuclear, hydro and renewables). In short, there is a massive amount of energy that can be extracted from biomass.

The question is whether such large-scale production and trade of biomass can be undertaken in a way that is beneficial and balanced with respect to (1) the social well being of the people involved, (2) the ecosystem (planet) and (3) the economy (profit). The authors explore the impact of these different contrasting interests on the potential (quantity) and the costs (per unit) of bioenergy.

A spectrum of sets of sustainability criteria is developed - ranging from loose definitions to the most stringent - and applied to two case-studies, one for the Ukraine and one for Rio Grande do Sul, a region in South-Eastern Brazil. These regions were chosen because sufficient previous research is available, and because they have been identified as promising bioenergy producers and exporters. Poplar production in Ukraine and eucalyptus production in Brazil are used as the reference biomass feedstock. These feedstocks can be converted into liquid fuels (bio-oil or synthetic biofuels) or be used as solid biofuels for combustion (generating heat and electricity):

biomass :: bioenergy :: biofuels :: energy :: sustainability :: social sustainability :: environmental sustainability :: plantations :: energy crops :: bioenergy trade :: Ukraine :: Brazil ::

biomass :: bioenergy :: biofuels :: energy :: sustainability :: social sustainability :: environmental sustainability :: plantations :: energy crops :: bioenergy trade :: Ukraine :: Brazil :: For both regions cost calculations are included for a representative intensive commercial short rotation forestry management system. The year 2015 was chosen as a target, because this allows a 10-year period required to implement changes in land-use, establish plantations and develop a framework to implement criteria.

Overall, the results of the study indicate that:

- In several key world regions, sustainable biomass production potentials can be very significant on foreseeable term (10-20 years from now). Feasible efficiency improvements in conventional agricultural management (up to moderate intensity in the case regions studied) can allow for production of large volumes of biomass for energy, without competing with food production, forest or nature conservation. The key pre-condition for such a development are improvements in the efficiency of agricultural management.

- It seems feasible to produce biomass for energy purposes at reasonable cost levels and meeting strict sustainability criteria at the same time. Setting strict criteria that generally demand that socio-economic and ecological impacts should improve compared to the current situation will make biomass production more expensive and will limit potential production levels (both crop yield and land surface) compared to a situation that no criteria are set. However, the estimated impact on biomass production costs and potential is far from prohibitive. For the case studied (SE Brazil and Ukraine) estimated biomass production costs under strict conditions are still attractive and in the range of €2/GJ for the largest part of the identified potentials. (Compare with oil: at US$ 60 per barrel and at approximately 6.1GJ per barrel, petroleum currently costs US$9.8/GJ, which is around €7.4/GJ. Compare with "typical" butiminous coal: at prices between US$55 and US$80 and at approximately 27GJ/ton, the price per GJ is between US$2.0 and US$2.9 or between €1.5/GJ and €2.2/GJ. More on the competitiveness of biomass, see previous post.)

- It should be noted that such improvements, when achieved, also represent an economic value, which could be considerable (e.g value of jobs, improvement of soil quality, and so on). Such ‘co-benefits’ could especially be relevant for the less productive, marginal lands. Such a valuation has however not been part of the study.

- The results are indicative, based on a desktop approach (and not on field research) and pay limited attention to macro-effects such as indirect employment and both potential negative and positive impacts on conventional agriculture. More work to verify and refine the methodological framework developed is therefore needed, preferably involving specific regional studies and including regional/national stakeholders.

The researchers came to the above conclusions in the following way.

127 sustainability criteria

A list of 127 criteria relevant for sustainable biomass production and trade is composed based on an extensive analysis of existing certification systems on e.g. forestry and agriculture.

To be able to analyse the impact of these criteria on the cost and potential of bioenergy, the various criteria needed to be translated into a set of concrete (measurable) criteria and indicators that have an impact on the management system (costs) or the land availability (quantity). 12 criteria are included in this study, because not all criteria could reasonably be translated into practically measurable indicators and/or measures and many criteria are related and/or overlap.

Because there is no generally accepted definition of sustainability - except from very broad and often symbolic principles, such as those set out at the Earth Summit in 1992 - , two sets of criteria and indicators - a strict and a loose one - are defined, to represent the difference in individual perceptions of sustainability. The stricter set of criteria is more difficult to implement than the loose set, because the restrictions for production and other activities in the chain are more severe.

The twelve criteria in their loose and strict definition are presented in the table at the beginning of this article - click to enlarge.

Applying these two sets of criteria to the province of Rio Grande do Sul in Brazil and to the Ukraine as a whole, results in changes in both the costs of producing biofuels, and their potential availability. A reference scenario is included showing the cost-supply curve as it would emerge if no criteria were implemented. This reference scenario comes close to the 'loose' set of criteria. Results for the factors related to employment and land use are excluded from this first analysis and described below.

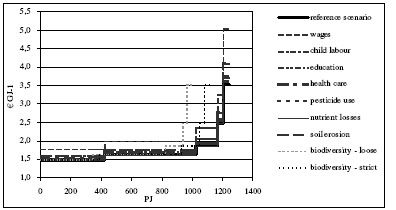

Figure 1 (click to enlarge). Cost supply curve for bioenergy crop production in a loose and strict set of criteria in Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, in 2015.

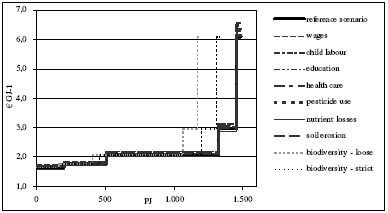

Figure 2 (click to enlarge). Cost supply curve for bioenergy crop production in a loose and strict set of criteria in Ukraine, in 2015.

Total costs for bioenergy crop production in Brazil and Ukraine are calculated at €1.5/GJ to €3.5/GJ and €1.7/GJ to €6.1/GJ dependant on the land suitability class (and respective yields), including the impact of basic levels for the various sustainability criteria.

These criteria can be further grouped into three clusters.

Land use, socio-economic factors, environment

Land use patterns

Land use patterns include criteria related to the avoidance of deforestation, competition with food production and protection of natural habitats. The theoretical potential to generate surplus agricultural land in 2015 was estimated, following the methodology of Smeets (earlier post). This methodology includes, among other variables, population growth, income growth and the efficiency of food production.

Results indicate that (in theory) large areas surplus agricultural land could be generated without further deforestation or endangering the food supply. However, additional investments in agricultural intensification may be required to realise these technical potentials.

Socio-economic criteria

Socio-economic criteria include criteria related to e.g. child labour, (minimum) wages, employment, health care and education. Compliance with the various criteria results in additional (non) wage labour costs, which are a separate cost item in the calculation of the production costs of biomass. The loose set of criteria does not influence the costs or quantity of bioenergy crop production. The strict criteria related to child labour, health care and education has a very limited impact on the costs of bioenergy crop production, between up to 8% in Ukraine and up to 14% in Brazil (see the tables).

The impact of the strict criterion related to wages is larger, which results in an increase of the costs of bioenergy crop production of up to 8% in Ukraine to up to 42% in Brazil. In general, the impact of the strict set of criteria is limited, because labour costs account for maximum two-fifth of the total production costs.

Another key socio-economic issue is the generation of direct and indirect employment. The direct impact of bioenergy crop production on employment is calculated based on the labour requirement for the various management activities.

The indirect impact of bioenergy crop production consists of two aspects. First, the employment effect of the increase in demand for agricultural machinery and other inputs due to bioenergy crop production and the intensification of food production. Second, the investments in agriculture require increasing the efficiency of food production, which may lead to more mechanisation and a loss of employment. Indirect (employment) effects of increased agricultural productivity and additional biomass production are very likely to be positive though. Due to a lack of data and suitable methodologies the indirect employment effects could not be calculated in the framework of this study, but these indirect effects could be significant and require further study.

Environmental criteria

Environmental criteria include criteria related to e.g. soil erosion, fresh water use, pollution from the use of fertilizers and agricultural chemicals. Compliance with various environmental criteria requires an adaptation of the bioenergy crop management system, e.g. an increase in mechanical and manual weeding to avoid the use of agricultural chemicals. For the loose set of criteria no additional costs were required.

The impact of the strict criteria related to soil erosion is limited to 15% and 4% maximum in Brazil and Ukraine, respectively. The impact of the strict set of criteria related to pollution from chemicals is up to 16% in Brazil and up to 6% in Ukraine.

The strict set of criteria related to nutrient leaching and soil depletion results in a cost decrease of up to –2% in Brazil and up to –4% in Ukraine, which is the combined effect of increasing labour and machinery costs and decreasing fertilizer costs.

For the protection of biodiversity protection, 10 to 20% of the surplus agricultural land could be set aside, although we acknowledge that this may be insufficient for the protection of biodiversity and that additional or other requirements for the plantation management may be required.

Due to a lack of data and suitable methodologies, indirect effects from the intensification of agriculture were not included, but these are potentially significant. A logical consequence would be that similar criteria should be in please for conventional agriculture as for biomass production.

The total costs increase by 35% to 88% in Brazil and 10% to 26% in Ukraine, dependant on the land suitability class (yield). The highest impact on costs (in €/oven dry ton) can be found on the lowest productive areas, because a large share of the costs are fixed, while the yield level depends on the land suitability class. For many of the areas of concern included in this study, data and methods used to quantify the impact of sustainability criteria on costs or potential are crude and therefore uncertain.

The ecological criteria require a more site-specific analysis with specific attention for e.g. soil type, slope gradient and rainfall. The social oriented criteria require more reliable and detailed data e.g. at a household level data and better methodologies to analyse indirect effects. Further research in this area is needed to provide more accurate estimates of the impact that various sustainability criteria may have on the costs and potential of bioenergy crop production.

Conclusion

The researchers propose an approach that provides an original and quantitative framework that can be used as a basis for designing sustainable biomass production systems and for monitoring existing ones.

They suggest that, besides more detailed and refined approaches, the framework may also be developed into a more simplified quickscan method to identify and monitor biomass production regions. Such a quickscan would be a useful tool for stakeholders - NGO's, governments, businesses, civil society organisations - to use as a guideline for discussions about particular projects or to craft policies.

The main conclusion of the report is that a very large amount of biomass for energy can be produced in the foreseeable future, especially in the developing world, and that this potential can be realised in a sustainable manner. Moreover, the biofuels thus produced, would be quite competitive with fossil fuels at current prices.

Finally, site-specific research remains crucial. A general, quantitative sustainability framework may offer a starting point, but it can never replace the particularities of actual projects that involve unique communities and eco-systems, all with their own histories and their visions on what the future should bring.

More information:

The International Energy Agency's Bioenergy website, with an overview of its different Bioenergy Task Forces.

The IEA's Bioenergy Task 40, which analyses all aspects of sustainable international bioenergy trade.

Fair Biotrade project (2001-2004): M. Juninger, "Overview of recent developments in sustainable biomass certification" [*.pdf] - a paper giving a comprehensive outline of initiatives on biomass certification from different viewpoints of stakeholders. The scope of this paper includes mainly new initiatives in the development of biomass certification system, though existing certification systems are also briefly described, as experiences from these systems provide valuable inputs. The study includes an inventory of initiatives in the field of biomass certification from the perspective of various stakeholder groups, such as NGOs, companies, national government and international bodies. A second objective of the paper is to identify opportunities and limitations in the development of biomass certification, and to present possible approaches onhow to introduce biomass certification systems. The paper finishes with some recommendations and conclusions.

IEA Bioenergy Task 40: Edward Smeets, André Faaij and Iris Lewandowski, "The impact of sustainability criteria on the costs and potentials of bioenergy production. An exploration of the impact of the implementation of sustainability criteria on the costs and potential of bioenergy production, applied for case studies in Brazil and Ukraine" [*.pdf], Utrecht University, Department of Science, Technology and Society, Copernicus Institute for Sustainable Development and Innovation, May, 2005.

Biopact: Brazilian ethanol is sustainable and has a very positive energy balance - IEA report, Oct. 8, 2006.

Biopact: A look at Africa's biofuels potential, July 30, 2007.

--------------

--------------

During a session of Kazakhstan's republican party congress, President Nursultan Nazarbayev announced plans to construct two large ethanol plants with the aim to produce biofuels for exports to Europe. Company 'KazAgro' and the 'akimats' (administrative units) of grain-growing regions will be charged to develop biodiesel, bioethanol and bioproducts.

During a session of Kazakhstan's republican party congress, President Nursultan Nazarbayev announced plans to construct two large ethanol plants with the aim to produce biofuels for exports to Europe. Company 'KazAgro' and the 'akimats' (administrative units) of grain-growing regions will be charged to develop biodiesel, bioethanol and bioproducts.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Links to this post:

Create a Link

<< Home