The bioeconomy at work: new success in engineering plant oils, replacing petrochemicals

As we progressively move towards the post-petroleum, bio-based economy, new breakthroughs in biotechnology become more frequent. The vision behind advocates of the bioeconomy is that all products derived from oil can and should gradually be replaced by biodegradable, efficient, climate neutral plant-based alternatives.

As we progressively move towards the post-petroleum, bio-based economy, new breakthroughs in biotechnology become more frequent. The vision behind advocates of the bioeconomy is that all products derived from oil can and should gradually be replaced by biodegradable, efficient, climate neutral plant-based alternatives.Researchers at the U.S. Department of Energy's Brookhaven National Laboratory, collaborating with scientists from the Georg-August University of Göttingen (Germany), have made another contribution to achieving this goal: using genetic manipulation to modify the activity of a plant enzyme, they succeeded in converting an unsaturated oil in the seeds of a temperate plant to the more saturated kind usually found in tropical plants, such as palm oil. The technique may yield materials that can replace petrochemicals. Interestingly, the process works in reverse: tropical oil-bearing plants can be triggered to deliver oils with a higher ratio of unsaturated fatty acids.

Potentially, the technique allows for a finetuned 'economy' of engineered oils, in which the metabolism of the seeds of oil bearing plants and the biosynthesis of the enzymes they rely on, is managed in such a way that it yields the ideal type of oil suited for the production of a particular product, be it biofuels with specific properties (cold tolerance, cloud point, melting point), green lubricants and resins, or bioplastics and biopolymers.

The research has been published online by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS):

biomass :: bioenergy :: energy :: sustainability :: vegetable oils :: fatty acids :: biofuels :: bioplastics :: bio-based :: genetic engineering :: biotechnology :: bioeconomy ::

biomass :: bioenergy :: energy :: sustainability :: vegetable oils :: fatty acids :: biofuels :: bioplastics :: bio-based :: genetic engineering :: biotechnology :: bioeconomy :: While conversion of an unsaturated oil to an oil with increased saturated fatty acid levels may not sound like a boon to those conscious about consuming unsaturated fats, "the development of new plant seed oils has several potential biotechnological applications," says Brookhaven biochemist John Shanklin, lead author on the paper.

For one thing, the new tropical-like oil has properties more like margarine than do temperate oils, but without the trans fatty acids commonly found in margarine products. Furthermore, engineered oils could be used to produce feedstocks for industrial processes in place of those currently obtained from petrochemicals. Shanklin also suggests that the genetic manipulation could work in the reverse to allow scientists to engineer more heart-healthy food oils.

"Scientists have known for a long time that the ratio of saturated to unsaturated fatty acids plays a key role in plants' ability to adapt to different climates, but to change this ratio specifically in seed oils without changing the climate is an interesting challenge," remarked Shanklin. "Our group sought to gain a better understanding of the enzymes and metabolic pathways that produce these oils to find ways to manipulate the accumulation of fats using genetic techniques."

The researchers focused on an enzyme known as KASII that normally elongates fatty acid chains by adding two carbon atoms. The longer 18-carbon chains are more likely to be acted on by enzymes that desaturate the fat. So the scientists hypothesized that if they could prevent the chain lengthening by reducing the levels of KASII, they could decrease the likelihood of desaturation and increase the level of saturated fats in the plant seeds.

Their hypothesis was supported by the fact that scientists had previously identified a plant with a mutated KASII that showed reduced enzyme activity, and these plants were able to accumulate more saturated fats than was normal. So the Brookhaven team set out to reduce KASII activity with the use of RNA-interference (RNAi) to see if they could further increase the level of saturation in plant seed oils.

The Brookhaven scientists performed their experiments on Arabidopsis, a plant commonly used in research. Like other plants from temperate climates (e.g., canola, soybean, and sunflower), Arabidopsis contains predominantly 18-carbon unsaturated fatty acids in its seed oil. Tropical plants, in contrast (e.g. palm), contain higher proportions (approximately 50 percent) of 16-carbon saturated fatty acids.

The results were surprising. The genetic manipulations that reduced KASII activity resulted in a seven-fold increase in 16-carbon unsaturated fatty acids - up to an unprecedented 53 percent - in the temperate Arabidopsis plant seed oils.

"These results demonstrate that manipulation of a single enzyme's activity is sufficient to convert the seed oil composition of Arabidopsis from that of a typical temperate pant to that of a tropical palm-like oil," Shanklin said. "It is fascinating - and potentially very useful - to know that we can change the oil composition so drastically by simple specific changes in seed oil metabolism, and that this process can occur independently from the adaptation to either tropical or temperate climates."

For example, such a technique could lead to the engineering of temperate crop plants to produce saturated oils as renewable feedstocks for industrial processes. Such renewable resources could help reduce dependence on petroleum.

Conversely, methods to increase the activity of KASII, and therefore the production of 18-carbon desaturated plant oils, may provide a useful strategy to limit the accumulation of saturated fatty acids in edible oils, leading to more healthful nutrition.

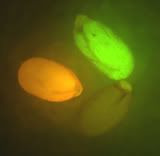

Picture: Arabidopsis seeds viewed through a fluorescence microscope. Two show the fluorescent markers used to track inserted genes; the third is an unmodified, wild type seed, which appears dark. Courtesy: BNL Media & Communications Office

More information:

Mark S. Pidkowich, Huu Tam Nguyen, Ingo Heilmann, Till Ischebeck, and John Shanklin, Modulating seed {beta}-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase II level converts the composition of a temperate seed oil to that of a palm-like tropical oil, [*abstract] Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 10.1073/pnas.0611141104, March 5, 2007

--------------

--------------

During a session of Kazakhstan's republican party congress, President Nursultan Nazarbayev announced plans to construct two large ethanol plants with the aim to produce biofuels for exports to Europe. Company 'KazAgro' and the 'akimats' (administrative units) of grain-growing regions will be charged to develop biodiesel, bioethanol and bioproducts.

During a session of Kazakhstan's republican party congress, President Nursultan Nazarbayev announced plans to construct two large ethanol plants with the aim to produce biofuels for exports to Europe. Company 'KazAgro' and the 'akimats' (administrative units) of grain-growing regions will be charged to develop biodiesel, bioethanol and bioproducts.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Links to this post:

Create a Link

<< Home