A closer look at Gynerium Sagittatum: a new plantation crop?

Earlier we reported on an interesting project in Peru, where a company will be using a wild but highly productive grass species for the production of bio-oil (previous post). The crop, Gynerium Sagittatum, known locally as 'caña brava', 'bitter cane', 'wild cane' or 'uva grass', is a potential plantation crop that may be established in tropical and subtropical areas in the future and serve as an energy crop.

Earlier we reported on an interesting project in Peru, where a company will be using a wild but highly productive grass species for the production of bio-oil (previous post). The crop, Gynerium Sagittatum, known locally as 'caña brava', 'bitter cane', 'wild cane' or 'uva grass', is a potential plantation crop that may be established in tropical and subtropical areas in the future and serve as an energy crop.The company in question, Samoa Fiber Holdings, has worked with the Peruvian Government for the creation of a Growers Association as a mechanism to allow indigenous peoples already familiar with the crop to harvest it from the wild to supply the pyrolysis plant.

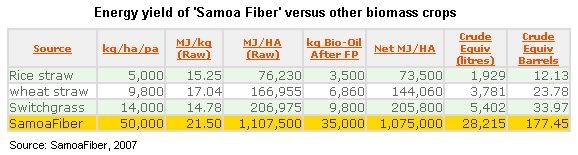

Samoa Fiber claims that if the cane (which it calls 'Samoa Fiber') is established as a plantation crop, it yields an average of 50MT/ha of dry biomass per year. This is more than three times the average yield of switchgrass, which is often used as a reference biomass crop (see table, click to enlarge). With the advent of a new generation of biochemical and thermochemical bioconversion technologies (cellulosic ethanol, biomass-to-liquids), biomass yields have become the single most important factor determining the viability of biofuel production. Applying highly efficient technologies on low yielding crops results in a low overal energy balance and makes the effort futile; starting out with abundant biomass resources results in the opposite equation.

Samoa Fiber claims that if the cane (which it calls 'Samoa Fiber') is established as a plantation crop, it yields an average of 50MT/ha of dry biomass per year. This is more than three times the average yield of switchgrass, which is often used as a reference biomass crop (see table, click to enlarge). With the advent of a new generation of biochemical and thermochemical bioconversion technologies (cellulosic ethanol, biomass-to-liquids), biomass yields have become the single most important factor determining the viability of biofuel production. Applying highly efficient technologies on low yielding crops results in a low overal energy balance and makes the effort futile; starting out with abundant biomass resources results in the opposite equation.Let us have a closer look at the cane, several properties of which might make it an ideal new energy crop for the tropics:

biomass :: bioenergy :: biofuels :: energy :: sustainability :: gynerium sagittatum :: energy crop :: plantation :: tropics :: energy balance :: biomass-to-liquids :: pyrolysis :: bio-oil ::

biomass :: bioenergy :: biofuels :: energy :: sustainability :: gynerium sagittatum :: energy crop :: plantation :: tropics :: energy balance :: biomass-to-liquids :: pyrolysis :: bio-oil :: General description

Gynerium Sagittatum is a giant reed, a member of the grass (Poceae) family that grows naturally and abundantly along the banks of tropical rivers in Latin America. Its culms are usually 5 or 6 m in height and 2 or 3 cm in diameter but may reach 10 m in height and 4 cm in diameter in Puerto Rico. The species varies from 5 to 14 m in height in the western Amazon Basin.

The culms arise from underground rhizomes which also produce weak and flexible lateral roots, mostly 1 mm or less in diameter. The culms have closely imbricated woody sheaths around a hard, woody exterior, and a fibrous interior. They are usually unbranched and taper little except near the top. The older leaves are shed, leaving a plainer, fan-like group near the apex. The leaf blades are 1 to 2 m long and have sharp serrulate margins. The clonal groups of plants are dioecious. The grayish-white plume-like terminal panicles are large, up to 2 m long. The male and female inflorescences are similar in appearance, but pistillate plants have a slightly fuzzy appearance because of hairy lemmas. The fruits are brown and about 1 mm long.

Range

Wild cane is native to the West Indies except the Bahamas, and from Mexico through Central America and South America to Paraguay. It is not known to have naturalized elsewhere. Two types coexist in the western Amazon Basin: a “small” and a “large” type that differ considerably in physical form and mode of reproduction.

Ecology

Wild cane grows on sites with moist soils, usually high in organic matter, often with the water table near the surface. These sites are seasonally flooded areas such as lake shores, swamps, river flood planes, or sand bars. The species grows at elevations from 10 to 1,600 m above sea level in Costa Rica. Wild cane resists damage from moderate flooding and sprouts after being covered with sediment. “Large type” stands in the western Amazon region vary in density from 0.6 to 2.6 culms/m2. Forest edges “shade out” portions of wild cane stands, and occasional trees grow up through stands and eventually suppress culms growing under their crowns. The species affects the course of forest succession. Apparently, disturbance that creates bare, wet soil is necessary for seedling establishment.

Reproduction

In some environments flowering occurs throughout the year, in others it occurs near the end of the low water period. The species is apparently wind pollinated. There are 1.67 million seeds/kg, and they can be expected to germinate between 3 and 7 days following sowing at temperatures between 20 and 30 °C.

Almost all the seeds of the “short” type from the Amazon Basin germinated within 3 weeks, and 0 to 2 percent of the “large” type germinated. Seeds are dispersed by wind and water. Vegetative propagation is also important, both for expanding colonies and establishing new ones.

Horizontal runners or rhizomes, surface or underground, are constantly active and establish new plants or clumps as far as 20 m from the parent plants. Segments of culm or rhizome, carried by floodwaters and covered with soil or debris, sprout and start new colonies.

Growth and Management

Growth of wild cane is rapid. Nursery seedlings reached 20, 30, and 50 cm after 1, 2, and 4 months. How long seedlings take to reach maturity and how rapidly suckers grow is unknown. Theoretically, baring catastrophes and invasion and shading by trees, clones can endure indefinitely. Culms of Amazon Basin plants produced close to 200 leaves during their lifetimes, having from 19 to 28 living leaves at a time.

Unbranched culms die after flowering, but only the branches of branched culms die. If not controlled, wild cane slowly invades wet bottomland pastures and eliminates forage plants. Periodic mowing appears to be adequate for control of advancing clumps.

Benefits and traditional uses

Wild cane provides cover for wildlife and protects stream banks from erosion. Its culms lack the strength and toughness of hardwoods and bamboo but still are used in rude construction, drying racks, vegetable stakes and fruit props, and for weaving mats, baskets, and hats. In the Amazon area, arrow shafts are made from the

dried culms. Plumes are used for dry floral arrangements.

Plantation potential

The seeds of the cane are sterile which makes it “non-invasive” when planted in plantations. Spread is easily controlled by monitoring the plantation perimeters. In addition, in the wild the cane exhibits “self thinning” over time.

Large plantations may be developed either with planting of stem pieces containing nodes or with seedlings produced by micro-cultivation techniques depending on size and relative labor costs. Further, unlike wild cane which is subject to alternate flooding and dry seasons, optimal hydration strategies can be worked out depending of the type of land.

More information:

John K. Francis, Gynerium sagittatum (Aubl.) Beauv. wild cane (POACEAE) [*.pdf], International Institute of Tropical Forestry.

Samoa Fiber Holdings: What is Samoa Fiber?

-------------------

-------------------

Spanish company Ferry Group is to invest €42/US$55.2 million in a project for the production of biomass fuel pellets in Bulgaria.

The 3-year project consists of establishing plantations of paulownia trees near the city of Tran. Paulownia is a fast-growing tree used for the commercial production of fuel pellets.

Spanish company Ferry Group is to invest €42/US$55.2 million in a project for the production of biomass fuel pellets in Bulgaria.

The 3-year project consists of establishing plantations of paulownia trees near the city of Tran. Paulownia is a fast-growing tree used for the commercial production of fuel pellets.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Links to this post:

Create a Link

<< Home