Energy to produce biofuels, from the world's largest dam

This is part two of our series on Africa's natural resource conflicts and on how the biorevolution could change the way these resources are used (part one). In this essay, Laurens Rademakers looks at an 'energy secret' hidden deep in one of Africa's largest and least well-known countries, the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Whenever we hear about the Democratic Republic of Congo, formerly known as Zaire, we read superlatives: the country has huge reserves of mineral wealth (gold, diamond, coltan, copper, uranium...), its vast land resources could make it the breadbasket of Central Africa, the country's main river, the Congo, is the second biggest on earth, hosting the second largest pristine rainforest after the Amazon, and when it comes to politics, the country has been in the hands of ruthless dictators for more than 3 decades. In Congo, everything is big, and so are the country's problems.

Whenever we hear about the Democratic Republic of Congo, formerly known as Zaire, we read superlatives: the country has huge reserves of mineral wealth (gold, diamond, coltan, copper, uranium...), its vast land resources could make it the breadbasket of Central Africa, the country's main river, the Congo, is the second biggest on earth, hosting the second largest pristine rainforest after the Amazon, and when it comes to politics, the country has been in the hands of ruthless dictators for more than 3 decades. In Congo, everything is big, and so are the country's problems.

Congo just came out of a bloody and underreported resource war which killed 4 million people, more than in any other conflict since the Second World War. After a cumbersome and complex transitional peace process, the country recently held its first democratic elections, which went smoothly, to the great relief of the UN and the international community (the country hosts the largest UN peacekeeping force, and the elections in the vast country were the most difficult the international community has ever had to organise.)

The Congolese now hope that the elections are a sign of a new era. One that will bring prosperity and stability, one that will exorcise the demons of the past and open a future where the Congolese are in control of their own destiny. Potentially, Congo could be one of the wealthiest nations in the global South, so the optimism is not entirely unfounded. But the tasks ahead are enormous. The State has to be reorganised, its infrastructure has to be rebuilt, social and health care systems have to be created, corruption has to be rooted out, hospitals, schools and universities have to be created, rebel factions have to be reintegrated into society... the list of things to revive, to rebuild and to reorganise is endless.

However, there is one resource that has been lying around, dormant and untouched for all these years, and it could be used to the great benefit of Congo's development in a relatively short time. In order for it to work, enormous investment is required though. But states, multinationals and world banks have been eyeing it for decades, and the plans are ready, the feasibility studies have been carried out, it's only a matter of getting together and working it. We are talking about the exploitation of the Congo river's vast energy potential, as it can be seen at the Inga Dams.

Bigger than the Three Gorges and the Itaipu combined

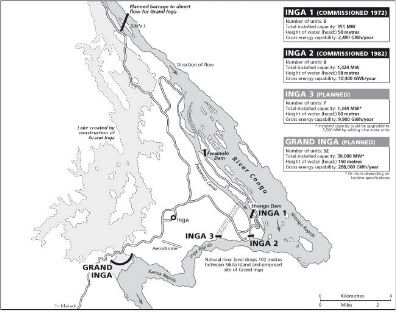

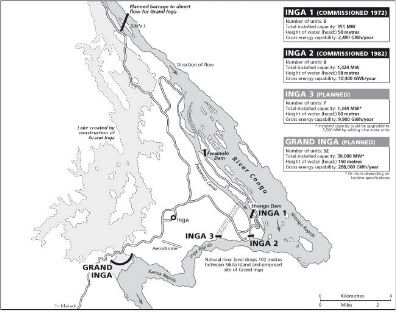

When the vast Congo river passes the capital Kinshasa and makes its way from the inland plateau to the Atlantic Ocean, the river rapidly descends over a short stretch. Some 150 kilometres from the coast, a series of rapids called les barrages d'Inga form a huge reservoir with a natural head of 150 metres (see picture). It is at this point where the potential for a hydroelectric complex of dams can be found. Back in the 1970s, dictator Mobutu already built a first series of small dams called "Inga I" with a capacity of 351MW, delivering 2400GWh of electricity per year. A decade later, "Inga II" was commissioned consisting of 8 units with a combined capacity of 1424MW and capability of 10,400GWh per year.

But it is the potential of Inga III and of the "Grand Inga" that has attracted attention. Combined, the projects have a hard to imagine total capacity of 42,000MW, making it the world's largest hydroelectric potential. Just think of what this means: the gigantic Three Gorges Dam in China, the world's largest, has a total capacity of 18,200MW; the world's second largest dam, the Itaipu on the Parana river located on the border between Brazil and Paraguay, has a capacity of 14,000MW. The Grand Inga would be bigger than both combined, and one can add two Grand Coulees to make up the total. Put differently, the Inga dams could provide more energy than 40 large nuclear power plants, more than 100 modern coal plants.

(See large map with statistics, here)

According to the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP), the Inga dams can, in principle, power the entire African continent and even export excess electricity to Europe. Projections show that the Grand Inga can lift Congo's 55 million people out of poverty all by itself. Investors such as South Africa's power company Eskom and the World Bank are ready to jump on the project, provided political stability reigns in the country.

Energy to mass-produce biofuels

But what does Inga's tantalizing potential have to do with biofuels and bioenergy? And why refer to a mega-project that has spun the heads of more than one megalomaniac, when otherwise the logic behind the biofuture is one of small-scale, localised and decentralised projects driving bottom-up approaches to development? The link is easy to understand:

ethanol :: biodiesel :: biofuels :: energy :: sustainability :: hydroelectric :: dam :: Inga :: Congo ::

ethanol :: biodiesel :: biofuels :: energy :: sustainability :: hydroelectric :: dam :: Inga :: Congo ::

First of all, the production of biofuels itself is energy intensive. In order to convert biomass into a high energy density liquid or gaseous fuel that can be used in vehicles, energy is required (either for distillation, transesterification, pyrolysis or gasification). Often, biomass residues are used to power this proces, as is the case in Brazil's ethanol industry, where distilleries are powered by bagasse (fibrous cane residue).

Critics have often pointed to the fact that some first generation biofuels, such as corn-ethanol, have a negative 'energy return on energy invested' (EROEI). They suggest that it takes more energy to plant, harvest and convert biomass, than you get out of the biofuel. Now for tropical energy crops, the energy balance is very positive (for sugar cane it is around 8, oil palm comes close to 12), but energy inputs remain an important cost factor.

Now it is not difficult to see where the Inga comes in. The cheap and abundant electricity from the huge dam complex could power a vast cluster of biofuel plants located nearby, that use biomass that was produced further in land, to make liquid biofuels ready for export.

A futuristic scenario

We have looked at the Congo's geography and infrastructure, and it is not unthinkable to see the following scenario develop in the near future: biomass from the country's vast inland production zones would be densified in decentralised plants, located alongside the Congo river. From there, the intermediate feedstocks are transported over the Congo to the capital Kinshasa, where rail would bring them to the port of Matadi. In that city, near the Atlantic Ocean, bioterminals and processing plants could be located, using the cheap and abundant electricity from the nearby Inga Dams.

In order to attract investments to realize the potential of the Inga Dams, a viable and large-scale industry would have to be in place, preferrably one that forms a synergy based on using raw materials coming from Congo itself. In previous decades, the idea was to use the Inga electricity to power the mining operations in Congo, but that would require a vast grid because the mining resources are located thousands of kilometres away from the dam, in the South-West of the country. Such an infrastructure was built, but has since decayed.

A biofuels industry would overcome this problem, as processing clusters and bioterminals aimed at exporting biofuels to the wider world could be located close-by. The exploitation of Congo's agricultural potential for the production of biofuels could thus be one step closer, because the problem of energy inputs has been solved.

Now this might all sound megalomaniacal, but there are some signs that tell us things might indeed go the way we sketched them here. The port of Antwerp, in Belgium (Congo's former colonial ruler) has recently announced that it will help build the harbors of Matadi [*Dutch] and Banana, in order to relaunch export activities in the country. Meanwhile, Antwerp itself is rapidly becoming a 'bioterminal' which imports raw and processed biomass and biofuels from all over the world to be distributed throughout Europe. In the future, the link might become more outspoken: 'bioterminal' Antwerp could become the importer of biofuels coming from 'bioport' Matadi or Banana.

One thing is certain, though: the Inga dam's enormous potential could power Africa out of electricity scarcity, and synergies between Congo's yet to be established bio-economy and the Inga could one day evolve into a highly efficient cluster of bioports and biorefineries, making Congo the Saudi Arabia of green energy.

Laurens Rademakers

Biopact, 2006, some rights reserved.

More information:

:: United Nations Environment Program: Congo River to Power Africa Out of Poverty - 24 February 2005

:: Afrol News: Congo River dam to industrialise Africa, Europe - February, 2005

:: Africa-energy.com: Large map of the Inga plans, showing a planned transcontinental grid to distribute the Inga electricity all over the continent and on to Europe (the same map can be found here).

Article continues

Whenever we hear about the Democratic Republic of Congo, formerly known as Zaire, we read superlatives: the country has huge reserves of mineral wealth (gold, diamond, coltan, copper, uranium...), its vast land resources could make it the breadbasket of Central Africa, the country's main river, the Congo, is the second biggest on earth, hosting the second largest pristine rainforest after the Amazon, and when it comes to politics, the country has been in the hands of ruthless dictators for more than 3 decades. In Congo, everything is big, and so are the country's problems.

Whenever we hear about the Democratic Republic of Congo, formerly known as Zaire, we read superlatives: the country has huge reserves of mineral wealth (gold, diamond, coltan, copper, uranium...), its vast land resources could make it the breadbasket of Central Africa, the country's main river, the Congo, is the second biggest on earth, hosting the second largest pristine rainforest after the Amazon, and when it comes to politics, the country has been in the hands of ruthless dictators for more than 3 decades. In Congo, everything is big, and so are the country's problems.Congo just came out of a bloody and underreported resource war which killed 4 million people, more than in any other conflict since the Second World War. After a cumbersome and complex transitional peace process, the country recently held its first democratic elections, which went smoothly, to the great relief of the UN and the international community (the country hosts the largest UN peacekeeping force, and the elections in the vast country were the most difficult the international community has ever had to organise.)

The Congolese now hope that the elections are a sign of a new era. One that will bring prosperity and stability, one that will exorcise the demons of the past and open a future where the Congolese are in control of their own destiny. Potentially, Congo could be one of the wealthiest nations in the global South, so the optimism is not entirely unfounded. But the tasks ahead are enormous. The State has to be reorganised, its infrastructure has to be rebuilt, social and health care systems have to be created, corruption has to be rooted out, hospitals, schools and universities have to be created, rebel factions have to be reintegrated into society... the list of things to revive, to rebuild and to reorganise is endless.

However, there is one resource that has been lying around, dormant and untouched for all these years, and it could be used to the great benefit of Congo's development in a relatively short time. In order for it to work, enormous investment is required though. But states, multinationals and world banks have been eyeing it for decades, and the plans are ready, the feasibility studies have been carried out, it's only a matter of getting together and working it. We are talking about the exploitation of the Congo river's vast energy potential, as it can be seen at the Inga Dams.

Bigger than the Three Gorges and the Itaipu combined

When the vast Congo river passes the capital Kinshasa and makes its way from the inland plateau to the Atlantic Ocean, the river rapidly descends over a short stretch. Some 150 kilometres from the coast, a series of rapids called les barrages d'Inga form a huge reservoir with a natural head of 150 metres (see picture). It is at this point where the potential for a hydroelectric complex of dams can be found. Back in the 1970s, dictator Mobutu already built a first series of small dams called "Inga I" with a capacity of 351MW, delivering 2400GWh of electricity per year. A decade later, "Inga II" was commissioned consisting of 8 units with a combined capacity of 1424MW and capability of 10,400GWh per year.

But it is the potential of Inga III and of the "Grand Inga" that has attracted attention. Combined, the projects have a hard to imagine total capacity of 42,000MW, making it the world's largest hydroelectric potential. Just think of what this means: the gigantic Three Gorges Dam in China, the world's largest, has a total capacity of 18,200MW; the world's second largest dam, the Itaipu on the Parana river located on the border between Brazil and Paraguay, has a capacity of 14,000MW. The Grand Inga would be bigger than both combined, and one can add two Grand Coulees to make up the total. Put differently, the Inga dams could provide more energy than 40 large nuclear power plants, more than 100 modern coal plants.

(See large map with statistics, here)

According to the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP), the Inga dams can, in principle, power the entire African continent and even export excess electricity to Europe. Projections show that the Grand Inga can lift Congo's 55 million people out of poverty all by itself. Investors such as South Africa's power company Eskom and the World Bank are ready to jump on the project, provided political stability reigns in the country.

Energy to mass-produce biofuels

But what does Inga's tantalizing potential have to do with biofuels and bioenergy? And why refer to a mega-project that has spun the heads of more than one megalomaniac, when otherwise the logic behind the biofuture is one of small-scale, localised and decentralised projects driving bottom-up approaches to development? The link is easy to understand:

ethanol :: biodiesel :: biofuels :: energy :: sustainability :: hydroelectric :: dam :: Inga :: Congo ::

ethanol :: biodiesel :: biofuels :: energy :: sustainability :: hydroelectric :: dam :: Inga :: Congo ::First of all, the production of biofuels itself is energy intensive. In order to convert biomass into a high energy density liquid or gaseous fuel that can be used in vehicles, energy is required (either for distillation, transesterification, pyrolysis or gasification). Often, biomass residues are used to power this proces, as is the case in Brazil's ethanol industry, where distilleries are powered by bagasse (fibrous cane residue).

Critics have often pointed to the fact that some first generation biofuels, such as corn-ethanol, have a negative 'energy return on energy invested' (EROEI). They suggest that it takes more energy to plant, harvest and convert biomass, than you get out of the biofuel. Now for tropical energy crops, the energy balance is very positive (for sugar cane it is around 8, oil palm comes close to 12), but energy inputs remain an important cost factor.

Now it is not difficult to see where the Inga comes in. The cheap and abundant electricity from the huge dam complex could power a vast cluster of biofuel plants located nearby, that use biomass that was produced further in land, to make liquid biofuels ready for export.

A futuristic scenario

We have looked at the Congo's geography and infrastructure, and it is not unthinkable to see the following scenario develop in the near future: biomass from the country's vast inland production zones would be densified in decentralised plants, located alongside the Congo river. From there, the intermediate feedstocks are transported over the Congo to the capital Kinshasa, where rail would bring them to the port of Matadi. In that city, near the Atlantic Ocean, bioterminals and processing plants could be located, using the cheap and abundant electricity from the nearby Inga Dams.

In order to attract investments to realize the potential of the Inga Dams, a viable and large-scale industry would have to be in place, preferrably one that forms a synergy based on using raw materials coming from Congo itself. In previous decades, the idea was to use the Inga electricity to power the mining operations in Congo, but that would require a vast grid because the mining resources are located thousands of kilometres away from the dam, in the South-West of the country. Such an infrastructure was built, but has since decayed.

A biofuels industry would overcome this problem, as processing clusters and bioterminals aimed at exporting biofuels to the wider world could be located close-by. The exploitation of Congo's agricultural potential for the production of biofuels could thus be one step closer, because the problem of energy inputs has been solved.

Now this might all sound megalomaniacal, but there are some signs that tell us things might indeed go the way we sketched them here. The port of Antwerp, in Belgium (Congo's former colonial ruler) has recently announced that it will help build the harbors of Matadi [*Dutch] and Banana, in order to relaunch export activities in the country. Meanwhile, Antwerp itself is rapidly becoming a 'bioterminal' which imports raw and processed biomass and biofuels from all over the world to be distributed throughout Europe. In the future, the link might become more outspoken: 'bioterminal' Antwerp could become the importer of biofuels coming from 'bioport' Matadi or Banana.

One thing is certain, though: the Inga dam's enormous potential could power Africa out of electricity scarcity, and synergies between Congo's yet to be established bio-economy and the Inga could one day evolve into a highly efficient cluster of bioports and biorefineries, making Congo the Saudi Arabia of green energy.

Laurens Rademakers

Biopact, 2006, some rights reserved.

More information:

:: United Nations Environment Program: Congo River to Power Africa Out of Poverty - 24 February 2005

:: Afrol News: Congo River dam to industrialise Africa, Europe - February, 2005

:: Africa-energy.com: Large map of the Inga plans, showing a planned transcontinental grid to distribute the Inga electricity all over the continent and on to Europe (the same map can be found here).

Article continues

-------------------

-------------------

Spanish company Ferry Group is to invest €42/US$55.2 million in a project for the production of biomass fuel pellets in Bulgaria.

The 3-year project consists of establishing plantations of paulownia trees near the city of Tran. Paulownia is a fast-growing tree used for the commercial production of fuel pellets.

Spanish company Ferry Group is to invest €42/US$55.2 million in a project for the production of biomass fuel pellets in Bulgaria.

The 3-year project consists of establishing plantations of paulownia trees near the city of Tran. Paulownia is a fast-growing tree used for the commercial production of fuel pellets.

Monday, September 04, 2006

Soybean farmers preparing for the biofuels scenario - doubts over sustainability

A worker moves soya beans in the hold of a ship bound for Amsterdam at the port of Santos near Sao Paulo, Brazil.

Big soybean farmers meeting in Paraguay have agreed to create an institution charged with minimizing the environmental and social costs associated with large-scale production of the crop. Soybeans are known to be one of the world's most destructive crops, responsible for the deforestation of vast swathes of rainforest. Recently, consumer pressure in Europe even resulted in the continent's main food chains banning soy that was produced on illegally logged land. The rise of the global biofuels industry, however, complicates the debate, because the 'green' fuels offer a huge new market (soybean oil is a preferred feedstock for biodiesel). This is why the second "Global Roundtable on Responsible Soybean" development has given itself 18 months to decide on "criteria and indicators" that will govern development of soybean farming and minimize the crop's negative environmental and social impacts, including the possibility of an "environmental friendly" soybean certification.

The two day meeting in Asuncion, Paraguay’s capital, took place with the backstage of international soaring energy prices, the alleged depletion of existing hydrocarbons resources and global enthusiasm on the launching of the biofuels option.

The forum brought together farmers from several producer countries in South America - Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, Bolivia and Uruguay - and from India, as well as members of environmental groups such as Worldwide Fund for Nature. Alberto Yanosky, director of the environmental group Guyra Paraguay and coordinator of the event is quoted saying that during the talks participants analyzed the negative aspects of the expansion of soy farming into rainforest areas, the misuse of pesticides, the migration of indigenous communities to urban areas due to large-scale production and the new world scenario of biofuels.

"We know that in some places the (crop's) advance has been at the expense of the forests" said the expert, who supports the idea of certifying products made from soybeans that are grown in areas where environmental norms are respected. "These are clear initiatives to halt the expansion of the agricultural frontier. We think the current area is sufficient to achieve the estimated production levels for the next five or ten years" added Yanosky.

Behind closed doors the infringement on the Amazon region and possible limits to Mercosur soybean cropland or reduction of extensive livestock farming were discussed as well as agrochemicals, soil depletion, the deterioration of working conditions and promoting more organic production. The world's leader in soybean production is United States with 85 million tons per year, followed by Brazil, 56 million tons; Argentina, 40 million; China, 16 million; India, 6 million and Paraguay, 3.7 million tons. However no representatives from the United States or China were present at the gathering.

We will closely follow up on this meeting and the sustainability criteria the 'Roundtable' comes up with. It will be very difficult to design credible criteria because after all, this is a monoculture industry, which, if it wants to expand, automatically puts pressure on forests. Direct logging for soy may become a thing of the past, but we fear the indirect pressures, involving a complex mechanism of different agro-industrial sectors interacting without nobody knowing who's really to blame for the end result which remains the same, deforestation. It is well known, for example, that in Brazil forest is logged to make way for pastures for cattle, after which the soybean industry moves in, receives the attention, while the cattle firms have meanwhile moved elsewhere, stealthily.

The palm oil industry faces similar problems, for which it too has created a "Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil", involving all major stakeholders. The results from this roundtable might be an indicator of what will come out of the Soybean panel. It will show that the bare fundamentals cannot be changed: these tropical monocultures prey on the world's last remaining rainforests, and if they want to expand, the forest always loses out.

At the Biopact we therefor continuously stress that the only way to arrive at really sustainable tropical biofuels, is by using crops that explicitely thrive on lands far away from rainforests (such as cassava, jatropha, or sorghum). [Entry ends here].

Article continues

posted by Biopact team at 7:05 PM 0 comments links to this post