Biofuels, mining and the scramble for Africa

This is part one of our series on Africa's resource conflicts and on how the bioenergy future might change the plight of the continent. Today, we focus on mining in Africa - by Laurens Rademakers

Let's start with a commonplace: Africa's wealth in natural resources is the single most important cause of the continent's misery. Gold, diamonds, uranium, cobalt, copper,... you name it, in Africa there's a mine full of it, and a violent conflict because of it. If you are the owner of a mobile phone, there's a piece of Congolese war in it, in the form of coltan. Your girlfriend's necklace could contain an African blood diamond.

Let's start with a commonplace: Africa's wealth in natural resources is the single most important cause of the continent's misery. Gold, diamonds, uranium, cobalt, copper,... you name it, in Africa there's a mine full of it, and a violent conflict because of it. If you are the owner of a mobile phone, there's a piece of Congolese war in it, in the form of coltan. Your girlfriend's necklace could contain an African blood diamond.

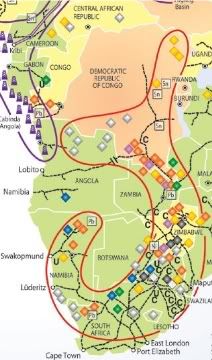

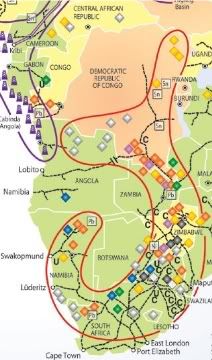

The stellar growth of China and India's economies puts pressure on these mineral commodities, and is fuelling a new scramble for Africa's resources. China is investing massively in infrastructure, mines, energy projects, ports and harbors to get the minerals out of the black continent as smoothly as possible. The human rights abuses that go with it, the lack of local social development, the enormous corruption - to China these are minor considerations. But the USA and France are pretty much playing the game along, trying to secure resources over which they claim some kind of ghost-sovereignty, based on their (colonial) past (see the brilliant piece "United States: the new scramble for Africa" in Le Monde Diplomatique) [And have a look at this large map to see what's at stake for France]. The UK, another major former colonial power, has been accused by the UN of looting part of the enormous mining resources of the Congo, which fuelled a horrible but underreported resource war that killed an estimated 4 million people - the most deadly conflict since WWII.

In short, super powers have a track record of causing misery in Africa because of their insatiable thirst for the continent's wealth. And with rising commodity prices, this situation is unlikely to change anywhere soon.

Check out Marcus Bleasdale's photo series "The Rape of a Nation" - about Congo's mines.

Two logics

The resource wars in Africa thrive on a hit-and-run logic whereby war lords create militias that terrorize local populations and force them to work in mines as slaves. Alliances change every day - creating chaos and uncertainty is the key to success. Everything happens in a very high, feverish tempo. Death, rape, slavery, and primitive capitalism mix in an obscene cocktail. Dig up the minerals, get them out. The war lords are mere proxies to Western companies and governments who are the final beneficiaries. Take this quite literally: at the Congo-Zambia border, Chinese, Indian, American, French and British trucks stand by to load tonnes of ores that have been hand dug by slaves in the war zone. Once they're out of the country, they end up on the world market as clean "commodities". And in your mobile phone.

This is globalization in its rawest form: a ruthless, violent form of exploitation, where people are considered to be expendable tools to be exploited by corporations who refuse to invest durably. Predatory capitalism.

Enter the bioenergy logic. As we have said before, it is one of local rootedness, slow growth, local and democratic resource control, durability, sustainability. It is this logic that can stabilize the volatile mining regions. Under the predatory logic, local men are often squeezed between two unpleasant choices: either become a militiaman and kill people, or become a slave and perish in the mines. And when a resource conflict does eventually end, the reintegration in society of former militiamen often remains a huge problem. The reason: lack of jobs, looting is more lucrative (this is what is happening today in the mining regions of Eastern and Southern Congo, Liberia, Sierra Leone, and South Sudan). Large-scale bioenergy projects could offer a way out - especially when they are part of mining operations.

Companies who could offer jobs do not invest in Africa's mines as long as there is no security. There is no security as long as there are no jobs. And as long as there are neither jobs, nor security, war lords and their predatory logic are in control. A vicious circle... But suppose a mining zone does get stabilized and investments are made, then it is crucial to keep it that way. Introducing bioenergy projects might be exactly the strategy to do so.

Obviously, this sounds idealistic, so let us make this more concrete. How could biofuels and bioenergy be used in mining operations? And what makes them so attractive that mining companies would really want to invest in them?

ethanol :: biodiesel :: biomass :: bioenergy :: biofuels :: energy :: mining :: sustainability :: Africa ::

ethanol :: biodiesel :: biomass :: bioenergy :: biofuels :: energy :: mining :: sustainability :: Africa ::

Mining and biofuels

First of all, bioenergy projects are job creation machines. By nature, they are agricultural projects, and most of them (at least in the tropics) rely on manual labor. The mere fact that they offer so many jobs, partly defuses the violent catch-22 that we discussed above.

But there are other advantages. Most obviously, rising energy costs and lack of local energy infrastructures impedes investments in mines. Bioenergy offers a solution. Mining companies are also often accused of polluting the environment through their unscrupulous use of water resources, their lack of care when it comes to preventing erosion and leaching, and the public health risks they cause when fine toxic particles pollute the air in the vicinity of their mine. The critique is most often entirely justified. And biofuels and bioenergy systems may offer solutions to many of these problems, once again.

A symbiosis can be created between the rough business of scratching the earth for ores, and the noble task of growing renewable, clean energy.

Bioremediation

A huge public health problem in the Copper Belt that stretches from Zambia far into Congo, is the lack of any pollution or air quality standards. The majority of those mines are open pits and once a patch is abandoned, the degraded land suffers under erosion and leaching; fine toxic particles get dispersed by the wind and spread out over vast regions; water bodies and streams get polluted. Local populations bear the burden and suffer under a range of respiratory diseases, while their bodies are gradually poisoned by trace elements in the water.

Biofuels plantations can rehabilitate these heavily degraded lands. Energy crops are not destined for human consumption, so they can be grown there. While they do, they fix the soil with their roots, preventing erosion, leaching and particle dispersion. They also replenish the soil with organic nutrients, gradually restoring the balance of the soil. At the same time, the crops provide a source of cleaner energy for the local mine. Several projects are underway with this bioremediation technique, involving for example jatropha shrubs.

Reducing energy costs

Mining is a very energy intensive industrial activity. It involves large machines scratching the earth for ores, carriages and trucks to transport the heavy loads to the surface, belts and crushers to refine the raw material. Many mines in the developing world have their own dedicated power stations, because they are located away from either the grid or the natural gas pipelines. Diesel fuel has to be imported often over very large distances. It is not surprising then that with today's high fossil fuel prices, energy has become the major operational cost for many mining operations (for many companies, this ranges between 25 and 30%).

This situation makes it logical to consider locally produced, dedicated bioenergy as an alternative. In fact, several mining companies are already investing in the idea. Energy plantations on mining grounds can take on the form of soil bioremediation systems, and in some circumstances as waste-water treatment systems (see below). Most fossil fuels used in mining operations - gas, solid fuels such as coal for electricity, or diesel fuel - have their green counterpart: biogas, solid biomass and liquid biofuels. In the tropics, these can already be produced competitively, cheaper than oil, gas and coal. Hence, mines in Africa could benefit tremendously from adopting bioenergy programs to power local operations.

Transport and logistics

But getting the ores out of the mine and to the export hubs costs energy too. Many of Africa's most productive mines are located far away from ports. An extensive network of railroads exists or is being built, but a large amount of the ores is still transported by truck. Traditionally, diesel fuel is imported by rail or truck to the mine, where trains and trucks then get refilled. Because of their landlocked location, the fuel costs involved in transporting the ores are increasing rapidly and eat away profit margins.

It is not difficult to understand that locally produced biofuels could cut transport costs considerably.

Waste-water management

Mines are known to deplete local water resources and to pollute streams and water bodies on which thousands of local people depend. In many countries in Africa this often amounts to a true public health disaster; water purification and waste-water management systems are simply non-existent at these mines, for lack of policies and laws.

One solution could come again from a bioenergy system based on the water hyacinth, a plant that thrives in (sub)tropical regions where it is often considered to be a major pest. However, in terms of raw biomass productivity, the water hyacinth is one of the most productive plants of the world, and it also happens to thrive on wastewater pollutants, especially heavy metals. This makes it an ideal plant for natural waste-water treatment, as several projects have already demonstrated. The artificial wastewater basins of mines are confined spaces, and growing water hyacinth in them diminishes the risk of the plant spreading to natural water bodies.

As the hyacinth grows so prolifically, it can be used as a major biomass feedstock for local biogas production [see previous post]. This gas in turn could be used to power mining operations.

Underground air quality

Research indicates that the use of biodiesel in a conventional diesel engine results in substantial reduction of unburned hydrocarbons, carbon monoxide, and particulate matter. Emissions of nitrogen oxides are either slightly reduced or slightly increased depending on the duty cycle and testing methods. The use of biodiesel decreases the solid carbon fraction of particulate matter (since the oxygen in biodiesel enables more complete combustion to CO2), eliminates the sulfate fraction (as there is no sulfur in the fuel), while the soluble, or hydrocarbon, fraction stays the same or is increased. Therefore, biodiesel works well with new technologies such as catalysts (which reduces the soluble fraction of diesel particulate but not the solid carbon fraction), particulate traps, and exhaust gas recirculation (potentially longer engine life due to less carbon). In underground mining, it betters the air quality considerably - an important advantage of the biofuel over fossil fuels.

As said, such targetted bioenergy projects create a considerable amount of local jobs. Interestingly, the local conditions in mining zones are such that biofuels projects solve another profound problem. As is well known, mining communities live in the vicinity of the mine, where the men do the labor, whereas the women have the task of growing their own food on heavily polluted patches of land. Even inside African mining towns, so-called cité-farming is practised on small plots. Now it makes sense to replace that dangerous practise which results in toxic food, by switching to biofuels production, an activity suited for women, who traditionally do most of the agricultural work. The simple equation becomes: grow biofuels instead of toxic food, and import healthy food from elsewhere with the income you made from growing energy.

This is just a rough overview of how bioenergy projects could benefit mining operations in Africa. These mines have a bloody, violent past, and we think bioenergy might radically alter that dreadful situation.

Laurens Rademakers

Biopact, 2006, some rights reserved.

Let's start with a commonplace: Africa's wealth in natural resources is the single most important cause of the continent's misery. Gold, diamonds, uranium, cobalt, copper,... you name it, in Africa there's a mine full of it, and a violent conflict because of it. If you are the owner of a mobile phone, there's a piece of Congolese war in it, in the form of coltan. Your girlfriend's necklace could contain an African blood diamond.

Let's start with a commonplace: Africa's wealth in natural resources is the single most important cause of the continent's misery. Gold, diamonds, uranium, cobalt, copper,... you name it, in Africa there's a mine full of it, and a violent conflict because of it. If you are the owner of a mobile phone, there's a piece of Congolese war in it, in the form of coltan. Your girlfriend's necklace could contain an African blood diamond.The stellar growth of China and India's economies puts pressure on these mineral commodities, and is fuelling a new scramble for Africa's resources. China is investing massively in infrastructure, mines, energy projects, ports and harbors to get the minerals out of the black continent as smoothly as possible. The human rights abuses that go with it, the lack of local social development, the enormous corruption - to China these are minor considerations. But the USA and France are pretty much playing the game along, trying to secure resources over which they claim some kind of ghost-sovereignty, based on their (colonial) past (see the brilliant piece "United States: the new scramble for Africa" in Le Monde Diplomatique) [And have a look at this large map to see what's at stake for France]. The UK, another major former colonial power, has been accused by the UN of looting part of the enormous mining resources of the Congo, which fuelled a horrible but underreported resource war that killed an estimated 4 million people - the most deadly conflict since WWII.

In short, super powers have a track record of causing misery in Africa because of their insatiable thirst for the continent's wealth. And with rising commodity prices, this situation is unlikely to change anywhere soon.

Check out Marcus Bleasdale's photo series "The Rape of a Nation" - about Congo's mines.

Two logics

The resource wars in Africa thrive on a hit-and-run logic whereby war lords create militias that terrorize local populations and force them to work in mines as slaves. Alliances change every day - creating chaos and uncertainty is the key to success. Everything happens in a very high, feverish tempo. Death, rape, slavery, and primitive capitalism mix in an obscene cocktail. Dig up the minerals, get them out. The war lords are mere proxies to Western companies and governments who are the final beneficiaries. Take this quite literally: at the Congo-Zambia border, Chinese, Indian, American, French and British trucks stand by to load tonnes of ores that have been hand dug by slaves in the war zone. Once they're out of the country, they end up on the world market as clean "commodities". And in your mobile phone.

This is globalization in its rawest form: a ruthless, violent form of exploitation, where people are considered to be expendable tools to be exploited by corporations who refuse to invest durably. Predatory capitalism.

Enter the bioenergy logic. As we have said before, it is one of local rootedness, slow growth, local and democratic resource control, durability, sustainability. It is this logic that can stabilize the volatile mining regions. Under the predatory logic, local men are often squeezed between two unpleasant choices: either become a militiaman and kill people, or become a slave and perish in the mines. And when a resource conflict does eventually end, the reintegration in society of former militiamen often remains a huge problem. The reason: lack of jobs, looting is more lucrative (this is what is happening today in the mining regions of Eastern and Southern Congo, Liberia, Sierra Leone, and South Sudan). Large-scale bioenergy projects could offer a way out - especially when they are part of mining operations.

Companies who could offer jobs do not invest in Africa's mines as long as there is no security. There is no security as long as there are no jobs. And as long as there are neither jobs, nor security, war lords and their predatory logic are in control. A vicious circle... But suppose a mining zone does get stabilized and investments are made, then it is crucial to keep it that way. Introducing bioenergy projects might be exactly the strategy to do so.

Obviously, this sounds idealistic, so let us make this more concrete. How could biofuels and bioenergy be used in mining operations? And what makes them so attractive that mining companies would really want to invest in them?

ethanol :: biodiesel :: biomass :: bioenergy :: biofuels :: energy :: mining :: sustainability :: Africa ::

ethanol :: biodiesel :: biomass :: bioenergy :: biofuels :: energy :: mining :: sustainability :: Africa :: Mining and biofuels

First of all, bioenergy projects are job creation machines. By nature, they are agricultural projects, and most of them (at least in the tropics) rely on manual labor. The mere fact that they offer so many jobs, partly defuses the violent catch-22 that we discussed above.

But there are other advantages. Most obviously, rising energy costs and lack of local energy infrastructures impedes investments in mines. Bioenergy offers a solution. Mining companies are also often accused of polluting the environment through their unscrupulous use of water resources, their lack of care when it comes to preventing erosion and leaching, and the public health risks they cause when fine toxic particles pollute the air in the vicinity of their mine. The critique is most often entirely justified. And biofuels and bioenergy systems may offer solutions to many of these problems, once again.

A symbiosis can be created between the rough business of scratching the earth for ores, and the noble task of growing renewable, clean energy.

Bioremediation

A huge public health problem in the Copper Belt that stretches from Zambia far into Congo, is the lack of any pollution or air quality standards. The majority of those mines are open pits and once a patch is abandoned, the degraded land suffers under erosion and leaching; fine toxic particles get dispersed by the wind and spread out over vast regions; water bodies and streams get polluted. Local populations bear the burden and suffer under a range of respiratory diseases, while their bodies are gradually poisoned by trace elements in the water.

Biofuels plantations can rehabilitate these heavily degraded lands. Energy crops are not destined for human consumption, so they can be grown there. While they do, they fix the soil with their roots, preventing erosion, leaching and particle dispersion. They also replenish the soil with organic nutrients, gradually restoring the balance of the soil. At the same time, the crops provide a source of cleaner energy for the local mine. Several projects are underway with this bioremediation technique, involving for example jatropha shrubs.

Reducing energy costs

Mining is a very energy intensive industrial activity. It involves large machines scratching the earth for ores, carriages and trucks to transport the heavy loads to the surface, belts and crushers to refine the raw material. Many mines in the developing world have their own dedicated power stations, because they are located away from either the grid or the natural gas pipelines. Diesel fuel has to be imported often over very large distances. It is not surprising then that with today's high fossil fuel prices, energy has become the major operational cost for many mining operations (for many companies, this ranges between 25 and 30%).

This situation makes it logical to consider locally produced, dedicated bioenergy as an alternative. In fact, several mining companies are already investing in the idea. Energy plantations on mining grounds can take on the form of soil bioremediation systems, and in some circumstances as waste-water treatment systems (see below). Most fossil fuels used in mining operations - gas, solid fuels such as coal for electricity, or diesel fuel - have their green counterpart: biogas, solid biomass and liquid biofuels. In the tropics, these can already be produced competitively, cheaper than oil, gas and coal. Hence, mines in Africa could benefit tremendously from adopting bioenergy programs to power local operations.

Transport and logistics

But getting the ores out of the mine and to the export hubs costs energy too. Many of Africa's most productive mines are located far away from ports. An extensive network of railroads exists or is being built, but a large amount of the ores is still transported by truck. Traditionally, diesel fuel is imported by rail or truck to the mine, where trains and trucks then get refilled. Because of their landlocked location, the fuel costs involved in transporting the ores are increasing rapidly and eat away profit margins.

It is not difficult to understand that locally produced biofuels could cut transport costs considerably.

Waste-water management

Mines are known to deplete local water resources and to pollute streams and water bodies on which thousands of local people depend. In many countries in Africa this often amounts to a true public health disaster; water purification and waste-water management systems are simply non-existent at these mines, for lack of policies and laws.

One solution could come again from a bioenergy system based on the water hyacinth, a plant that thrives in (sub)tropical regions where it is often considered to be a major pest. However, in terms of raw biomass productivity, the water hyacinth is one of the most productive plants of the world, and it also happens to thrive on wastewater pollutants, especially heavy metals. This makes it an ideal plant for natural waste-water treatment, as several projects have already demonstrated. The artificial wastewater basins of mines are confined spaces, and growing water hyacinth in them diminishes the risk of the plant spreading to natural water bodies.

As the hyacinth grows so prolifically, it can be used as a major biomass feedstock for local biogas production [see previous post]. This gas in turn could be used to power mining operations.

Underground air quality

Research indicates that the use of biodiesel in a conventional diesel engine results in substantial reduction of unburned hydrocarbons, carbon monoxide, and particulate matter. Emissions of nitrogen oxides are either slightly reduced or slightly increased depending on the duty cycle and testing methods. The use of biodiesel decreases the solid carbon fraction of particulate matter (since the oxygen in biodiesel enables more complete combustion to CO2), eliminates the sulfate fraction (as there is no sulfur in the fuel), while the soluble, or hydrocarbon, fraction stays the same or is increased. Therefore, biodiesel works well with new technologies such as catalysts (which reduces the soluble fraction of diesel particulate but not the solid carbon fraction), particulate traps, and exhaust gas recirculation (potentially longer engine life due to less carbon). In underground mining, it betters the air quality considerably - an important advantage of the biofuel over fossil fuels.

As said, such targetted bioenergy projects create a considerable amount of local jobs. Interestingly, the local conditions in mining zones are such that biofuels projects solve another profound problem. As is well known, mining communities live in the vicinity of the mine, where the men do the labor, whereas the women have the task of growing their own food on heavily polluted patches of land. Even inside African mining towns, so-called cité-farming is practised on small plots. Now it makes sense to replace that dangerous practise which results in toxic food, by switching to biofuels production, an activity suited for women, who traditionally do most of the agricultural work. The simple equation becomes: grow biofuels instead of toxic food, and import healthy food from elsewhere with the income you made from growing energy.

This is just a rough overview of how bioenergy projects could benefit mining operations in Africa. These mines have a bloody, violent past, and we think bioenergy might radically alter that dreadful situation.

Laurens Rademakers

Biopact, 2006, some rights reserved.

-------------------

-------------------

Spanish company Ferry Group is to invest €42/US$55.2 million in a project for the production of biomass fuel pellets in Bulgaria.

The 3-year project consists of establishing plantations of paulownia trees near the city of Tran. Paulownia is a fast-growing tree used for the commercial production of fuel pellets.

Spanish company Ferry Group is to invest €42/US$55.2 million in a project for the production of biomass fuel pellets in Bulgaria.

The 3-year project consists of establishing plantations of paulownia trees near the city of Tran. Paulownia is a fast-growing tree used for the commercial production of fuel pellets.

1 Comments:

Interesting piece, I didn't know Afric had such large mineral reserves.

But what makes you think biofuels plantations will not become a part of the very "resource wars" you're trying to end?

BB

Post a Comment

Links to this post:

Create a Link

<< Home