|

About | Contact | Mongabay on Facebook | Mongabay on Twitter | Subscribe |

|

Finding new speciesBy Jeremy Hance, mongabay.comOctober 21, 2010 Species discovery: how do scientists find and describe new species—and the answer to other taxonomy questions

Currently scientists have described 1.9 million species from Balaenoptera musculus (the blue whale) to Oxysternon festivum (the red dung beetle), yet conservative estimates of the number of species on Earth range anywhere from 10 to 20 million species (some estimates jump to 100 million). If bacteria are added to this list then the number of species on Earth likely jumps another 10 million or so.

The search for species is even more pressing now that scientists believe we are either entering or already in the midst of a mass extinction. Due to a variety of human driven impacts—including deforestation, habitat loss, pollution, climate change, invasive species, and overexploitation such as through bushmeat or the pet trade—species populations are falling worldwide.

But how do scientists find and describe new species? The process of describing species When describing a new species, scientists must collect a 'type specimen': this means a dead individual of the species. There have been a few instances where photographs including other genetic samples have been used to describe a new species successfully, and no individual is killed, but these are currently much in the minority.

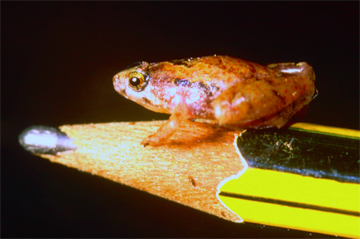

Once the species is determined as new to science, researchers write a formal description of it, take photos and/or provide illustrations, and invent a new scientific name. After completing the paper, researchers then submit it to a scientific journal. The editor of the journal will circulate the new finding to other experts with those particular types of animals or plants. If the other experts agree that the new species is valid, the journal accepts the paper and the specimen officially becomes a new species. This process is long and often takes years between initial discovery and formal acceptance of the new species. Cryptic species throw a wrench into this: these are species that look remarkably similar to another species, but are genetically unique. DNA is increasingly being used as a tool to determine new species as well as to discover the relationship between previously known species. Finding species: where are the unknown species hiding? If you want to earn scientific fame by discovering a new species, here are a few tips: think small, think underwater or underground, and think invertebrates and plants. This is not to imply that all the world's large land-dwelling species have been found—just this year researchers announced the discoveries of a new species of monitor lizard that was as long as a adult human, a new monkey from the Brazilian Amazon, and a new carnivorous mammal from a lake in Madagascar—but such discoveries are more a matter of right place-right time over persistence. While scientists still find new species in terrestrial ecosystems, a single dive to the depths of the ocean is likely to produce a new species. Cave systems have also yielded a number of new species, especially those that have only recently been explained. When it comes to types of species, insects are the most commonly discovered: thousands of new insects are found every year. Beetles are the most numerous. History of species discovery and description The history of species discovery and description is not only exciting—madness, exploration, untimely demise—it is also important for understanding the structure taxonomists use to describe species, for example the reason why every species is known by two Latinized names—the scientific name—one representing the genus and the other the species. While the effort to categorize species stretches far back in history—Aristotle attempted it—today's modern system of categorizing and naming species largely stems from 18th Century Swedish scientist, Carl Linnaeus. In two seminal works—Species Plantarum and Systema Naturae—Linnaeus outlined the hierarchal structure employed today for classifying species. Latin was the language of choice, because it was dead and therefore fixed. Within his works, Linnaeus classified thousands of plants and animals from all around the world with Latinized names. But Linnaeus didn't just build a structure to categorize species that would last to present-day, he was also instrumental in pushing the science of taxonomy further. As one of the most influential scientists of his day, Linnaeus chose and funded young biologist to travel the world, find new species, and return to him with specimens. These students have come to be known as 'the apostles of Linnaeus'. Seven of these 'apostles' died on their explorations, a couple went mad or became addicts, but many brought home species from as far away as China, South Africa, and the Amazon. Linnaeus updated While Linnaeus, with help from his traveling apostles, began the formal and large-scale effort to describe the world's life-forms, it has, of course, changed considerably in over two hundred years. When biologists refer to species today they often give the year of the species' formal description and the scientist who described it. For example, the well-known panda bear is Ailuropoda melanoleuca David, 1869. Also contemporary scientists categorize a species according to where it fits in the evolutionary tree, a concept that would have been unknown to Linnaeus as he developed his system over a hundred years before Darwin outlined the theory of evolution. In other words, animals that share the same genus are more closely related in evolutionary terms than animals that share only the same family. Instead of relying on five classifications, as Linnaeus did, researchers have developed a seven rung hierarchy to describe a unique life form: kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, genus, and species. For example, the tiger, which was described by Linnaeus, is classified in descending order as anamalia (animal), chordate (vertebrates), mammalia (mammals), carnivore (carnivores or mostly meat-eaters), felidae (cats), panthera (cats that roar), and tigris (the tiger). The tiger is additionally further separated into six surviving subspecies and three extinct subspecies. Subspecies are a puzzling and at times difficult classification that establishes when a species has clearly splintered into distinct populations, usually geographically separated, but has not yet evolved far enough from each other to be considered separate species. One could think of a subspecies as unconnected populations: in other words the distinct populations would interbreed if they could, yet something—most often a physical barrier—is making interbreeding impossible. Debates over whether or not an animal is a unique species or simply a subspecies can be complex, rowdy, and linger for decades. This is because the debate over subspecies and species has real-world consequences: subspecies are rarely given conservation attention and funding. One example of a subspecies in flux is the forest elephant from the African Congo. The forest elephant is considered by some scientists to be distinct enough from the African elephant to be considered its own species, others, however, claim it is only a subspecies. If the forest elephant was accepted as a species today, the effort to save it from extinction would likely gain sudden life and an influx of funding. On the other side, if too many 'subspecies' are upgraded without cause, conservationists worry it could 'cheapen' the idea of a species. Articles on recent species discoveries [an error occurred while processing this directive] News index | RSS | News Feed | Twitter | Home Advertisements:

|

|

|

WEEKLY NEWSLETTER

Photos HIGH RESOLUTION PHOTOS / PRINTS

CALENDARS

CANVAS BAGS

MONGABAY BLOG

Loading...

|

| | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Copyright mongabay 2010 Carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions generated from mongabay.com operations (server, data transfer, travel) are mitigated through an association with Anthrotect, an organization working with Afro-indigenous and Embera communities to protect forests in Colombia's Darien region. Anthrotect is protecting the habitat of mongabay's mascot: the scale-crested pygmy tyrant. |