The spirit of Rudolf Diesel: peanuts and socialism

Rudolf Diesel was a great inventor and a typical 'universal man', an erudite whose interests ranged from mechanics and physics to linguistics and sociology. The french-born German inventor's biography reads like a Greek tragedy, with his deportation to London during the Franco-Prussian War, his brilliant career as a student, the disputes surrounding his patents and business deals, his rise to the status of multi-millionaire, and his political activism as an internationalist and socialist which contrasted with his wealth. His huge debt in later life, the peculiarities of his psyche (mildly paranoid) and his suspicious death (suicide or murder), add to the suspense.

Rudolf Diesel was a great inventor and a typical 'universal man', an erudite whose interests ranged from mechanics and physics to linguistics and sociology. The french-born German inventor's biography reads like a Greek tragedy, with his deportation to London during the Franco-Prussian War, his brilliant career as a student, the disputes surrounding his patents and business deals, his rise to the status of multi-millionaire, and his political activism as an internationalist and socialist which contrasted with his wealth. His huge debt in later life, the peculiarities of his psyche (mildly paranoid) and his suspicious death (suicide or murder), add to the suspense.For biofuel advocates, Diesel has become somewhat of a symbol, but for rather humble reasons: at the Exposition Universelle of 1900 in Paris, he demonstrated his revolutionary engine by using pure peanut oil as fuel. His own words have inspired many biodiesel enthusiasts eversince: "The use of vegetable oils for engine fuels may seem insignificant today. But such oils may become in the course of time as important as the petroleum and coal tar products of the present time" (1912).

Wealth, socialism, energy, engines and peanuts. A bizarre combination. But one that might work in the future. Suppose we were to take Diesel's vision of peanut-oil fueled engines seriously, then the question obviously becomes: where will all the peanuts come from? The answer immediately takes us to the sub-tropics, and in particular to the Sahel in Africa.

Peanuts, an important oil crop

Peanuts or groundnuts (Arachis hypogaea L.) are a nitrogen-fixating legume that is cultivated in over 100 countries in the global south [overview at the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics]. It is the 13th most important food crop of the world. Today, groundnut is the world's 4th most important source of edible oil and the 3rd most important source of vegetable protein. Groundnut seeds contain high quality oil (50%), easily digestible protein (25%) and carbohydrates (20%).

The nut is currently grown on 26.4 million ha worldwide with a total production of 36.1 million metric tons, and an average productivity of 1.4 metric tons per hectare. Major groundnut producers in the world are: China, India, Nigeria, USA, Indonesia and Sudan. Developing countries account for 96% of the global groundnut area and 92% of the global production.

Globally, 50% of groundnut produce is used for oil extraction, 37% for confectionery use and 12 % for seed purpose. Groundnut haulms (vegetative plant parts) provide excellent hay for feeding livestock. They are rich in protein and have better palatability and digestibility than other fodder. The production of groundnuts is concentrated in Asia and Africa, where the crop is grown mostly by smallholder farmers under rain-fed conditions with limited inputs.

Groundnut as a biofuel feedstock

Groundnut is an interesting energy crop for several reasons:

- it grows well in semi-arid regions and requires limited fertilizer and water inputs

- therefor it does not cause any pressures on rainforest ecologies, a critique often raised against other tropical energy crops (most notably palm oil)

- the regions where groundnut thrives are populated by the world's poorest people (especially Sahelian countries, like Mali, Niger, Mauritania, Chad, the Central African Republic, Sudan -- who all rank at the bottom of the scale of, for example, the Human Development Index)

- many non-commercial and non-edible varieties with high yields can be developed and improved (with several such varieties being tested in Georgia, U.S. - see below)

- In contrast to other energy crops which thrive well in semi-arid regions, such as the perennial shrubs jatropha curcas and pongamia pinnata, groundnut can be harvested mechanically

- the nuts themselves have a high oil content (around 50%) and one hectare of groundnut yields around 1000 litres of oil; the oil has a relatively low melting point, a medium iodine value and a high flash-point - characteristics which make it a suitable oil for biodiesel production

- the groundnut has a residue-to-product ratio (earlier post) of around 0.5-1.2 for pods and 2.2-2.9 for straw; this means that for every ton of nuts produced, 500 to 1200kg of shells become available and 2.2 to 2.9 tons of straw residue are harvested; in total groundnut yields between 3.7 and 5.1 tons of biomass per hectare

- these residues offer an interesting solid biofuel, with a relatively high energy content of 16Mj/kg for shells and 18Mj/kg for straw - with advanced bioconversion technologies (cellulosic ethanol or dry pyrolisis) this 'waste' biomass can be turned into liquid fuels and bioproducts; alternatively, it could be densified and used in biomass (co-firing) power plants

According to the African Groundnut Council, there are several projects underway with peanut oil as a biodiesel feedstock (in Europe and Brazil) and the nut's byproducts make it a crop with potential applications outside biodiesel production. The use of compacted groundnut shells in the form of 'bio-coal' (fuel briquettes) may save millions of hectares of woodlands which are under pressure because they are a source of firewood. This could be a very effective strategy for tackling desertification in the Sahel:

biodiesel :: biomass :: bioenergy :: biofuels :: energy :: sustainability :: Sahel :: briquettes :: peanuts :: groundnut :: diesel ::

biodiesel :: biomass :: bioenergy :: biofuels :: energy :: sustainability :: Sahel :: briquettes :: peanuts :: groundnut :: diesel :: Peanut economics

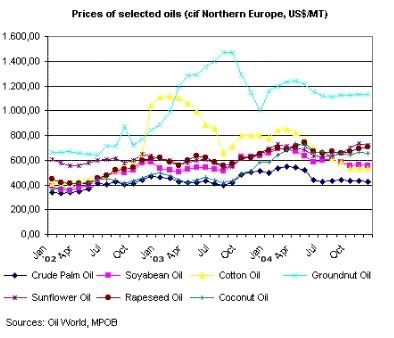

The major hurdle facing the adoption of groundnut as an energy crop, is the economics of groundnut oil. As such, peanut oil is one of the more expensive vegetable oils on the market, often fetching twice the price of palm oil.

But the trend could quickly be reversed if the global biofuels industry keeps growing as it is doing today, with multi-feedstock biodiesel plants searching for and processing any a diversity of vegetable oils. Moreover, planting and harvesting alternative energy crops grown in semi-arid regions, like jatropha and pongamia, requires vast amounts of manual labor, whereas peanuts do not. They can be planted and harvested mechanically, which allows for a very rapid expansion of the hectarage. Finally, land prices in these Sahelian countries are the lowest in the world, whereas prices for land suitable for tropical biofuel crops (like sugar cane or oil palm) are considerably higher. When the biofuels industry expands, land (lease) costs and harvesting costs might become very important business factors. And on both, groundnuts have a competitive advantage.

The best bet however is to use and develop non-commercial varieties of the nut, with higher yields. These varieties exist but have so far not been cultivated because they cannot be sold on the edible oils market. This is where farmers and agronomists from Georgia come in.

Tests are under way at the University of Georgia to develop non-edible peanuts that are high in oil, and could be grown specifically for biodiesel production. These varieties are higher in oil content than currently grown runner and Virginia type varieties and would not compete on the world market with peanuts grown for food and commercial cooking oil products.

Georgia Brown is a commercially grown peanut that is high in oil content, but not good for commercial oil. Georganic is a test variety that is high in oil, low in input costs and not suitable for commercial use. Georganic, or similar varieties will likely be the future of peanut biodiesel, according to Daniel Geller, a research engineer at the University of Georgia.

“Running peanut biodiesel cleans residue from a diesel engine. This can be good and bad, because the particles tend to clog up the filter on an engine. After cleaning the filters a few times, peanut biodiesel actually runs much cleaner than diesel,” Geller explains.

Worldwide, the demand for alternative fuels is huge. In the U.S. the demand is critical. The U.S. has roughly six percent of the world’s population, but consumes nearly 25 percent of all the fossil fuel produced worldwide. Whether biodiesel from peanuts becomes a popular alternative to fossil fuel depends on the economics of peanut oil worldwide.

More information:

Diesel, The Man and the Engine. Morton Grosser. New le der Erstausgabe von 1913 mit einer technik-historischen Einführung. Moers: Steiger Verlag, 1984.

International Crop Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT), groundnut information.

African Groundnut Council: Groundnuts, an alternative source of energy for transportation.

African Groundnut Council: New Source of Energy From Groundnut - combatting desertification through groundnut shell briquettes

Farm Press: Georgia working with peanuts as biodiesel source - Sept.11, 2006

-------------------

-------------------

Spanish company Ferry Group is to invest €42/US$55.2 million in a project for the production of biomass fuel pellets in Bulgaria.

The 3-year project consists of establishing plantations of paulownia trees near the city of Tran. Paulownia is a fast-growing tree used for the commercial production of fuel pellets.

Spanish company Ferry Group is to invest €42/US$55.2 million in a project for the production of biomass fuel pellets in Bulgaria.

The 3-year project consists of establishing plantations of paulownia trees near the city of Tran. Paulownia is a fast-growing tree used for the commercial production of fuel pellets.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Links to this post:

Create a Link

<< Home